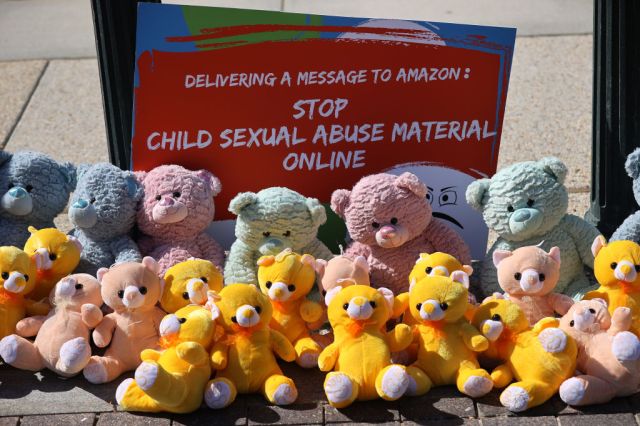

Parents protest: 45 million images of child abuse were reported by tech companies last year. Credit: Chip Somodevilla / Getty

Forty five million photos and videos of child sexual abuse were reported by technology companies last year. Forty five million. Every single one of those is a documentary of violence against a child; and every time one of them is downloaded, that child’s pain and shame is relived for the pleasure of the viewer. So how many viewers are there for this vast catalogue of agonies? Enough that in 2017, Simon Bailey, the National Police Chiefs’ Council lead for child protection, claimed they could no longer deal with the volume of offences.

Every month, 400 men are arrested for viewing indecent images of children. Instead of charging and prosecuting them, Bailey suggested they be put on the sex offenders register, and given counselling and rehabilitation. This seems an outrageous proposition: how is it not an insult to the victims and a derogation of morality to treat looking at (and, let’s not forget, masturbating to) pictures of child abuse as such a low-level thing?

But in practice, it’s already common for men convicted of these offences – even those involving category A images, the most serious kind – to receive non-custodial sentences with a rehabilitation requirement. It’s probably not irrelevant here that these are often white-collar criminals, middle-class men with middle-class jobs and families. They acted monstrously, but they don’t look like monsters. Even if they did, it’s hard to see where an already overcrowded prison service would fit so many extra occupants, and hard to argue that prison has any solid track record of improving the character of those who pass through it.

So, there is a problem. What should be done with these 400 newly minted paedophiles each month. That is the subject of a documentary to be broadcast on BBC Three, which asks: Can Sex Offenders Change? Presenter Becky Southworth, a victim of sexual abuse by her father, talks to men with convictions for sexual offences involving children who are involved in treatment programmes, and to some of the experts providing the treatment. “I don’t want there to be any more victims,” she says. “I want to believe these programmes are actually working.”

What she doesn’t say is that treatment of sex offenders has a dubious history. Last year, it was ruled that the Ministry of Justice unlawfully continued the use of the Sex Offender Treatment Programme for five years after the evidence showed it was ineffective – or rather, that if it had any effect at all, it was to make participants more likely to offend.

A report into the treatment programme found it was effectively a networking opportunity for paedophiles: “When stories are shared, their behaviour may not be seen as wrong or different; or at worst, contacts and sources associated with sexual offending may be shared.”

The experts Southworth meets are not involved in that discredited programme, and claim good success rates – Belinda Winder, of the Safer Living Foundation, tells Southworth that of 60 high-risk offenders the foundation has worked with, only one has reoffended. The perpetrators give a closer view of what that success might look like, and it isn’t easy to sympathise with.

They fall into two broad camps. On one side, there are men like “Kyle” (all the men’s names have been changed and their identities obscured), whose compulsive use of pornography led them into more and more extreme territory, including imagery of children. They often describe themselves as “addicted” and attribute their crimes to stress.

On the other, there are those like “Andrew” who are sexually attracted to children – the “true paedophile”. It’s “Andrew” who causes Southworth the most concern. “He talks about his attraction to children as a sexuality,” she says, “and for me a sexuality isn’t something you can change, even with therapy.”

One thing the experts emphasise is that ostracising these men is the worst possible thing. The more they’re cut off from society, the less they have to lose from acting on their impulses. It’s one thing to hear that, and another to be confronted with the reality of “Vicky” who has stood by her partner “Chris” after his conviction for accessing child abuse images. Southworth starts by wondering how anyone could stay with a man like that, but at the end of their conversation, the question is more one of what “Vicky” is getting out of this. It might be good for society, but it doesn’t seem great for her.

With “Andrew”, the bar to empathy is even higher. He claims that early trauma has fixed him in a child-like mentality of which his paedophilia is one expression: Becky, who knows more than most people about trauma, gives a look of peerless scepticism to the camera at this point. The problem is that “Andrew” as a concrete person, rather than an abstraction, is pretty disgusting: when he complains that “I’m treated like a predator, but in reality I’ve always been much closer to a victim,” you wonder what room his philosophy contains for the actual victims in the images he used.

Maybe “Andrew” will read me calling him disgusting, though, and spiral into more offending. What is there to hold men like him back from acting on their desires? They know they’re held in public contempt. The only place they get to feel normal is with others who share their transgression – the main way images of child abuse proliferate is by informal distribution through paedophile networks. The men Southworth meets are reprehensible people, or at any rate, people who’ve done reprehensible things. Experts say their rehabilitation depends on them learning to think of themselves as not wholly reprehensible. It’s hard to stomach.

Like Southworth, I started this documentary wanting to believe sex offenders can change. I ended it with profound admiration for the people providing the programmes, because it turns out this is a point where my compassion cannot pass.

I want these men to live in shame of what they’ve done and terror of what would happen to them if anyone found out. I want them to have their second chance in theory, but in practice I can’t think of a single one I think they deserve. I want them to disappear. Instead, there are 400 more of them every month.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe