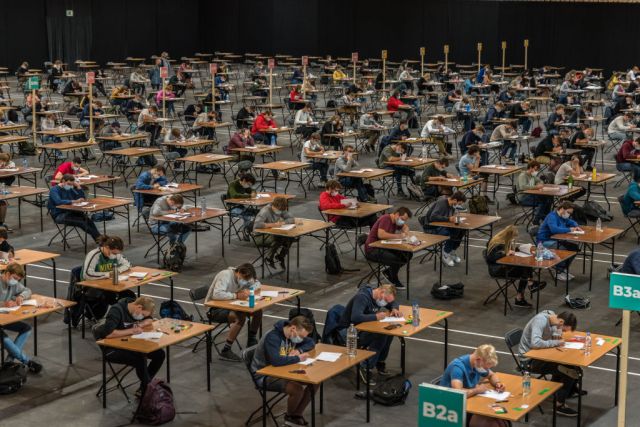

Exams: the worst form of assessment apart from all the others. Jonathan Raa/NurPhoto via Getty

Our public examination system is a resilient beast. During The Second World War some exams were held in air raid shelters while bombs rained down from above. Records exist of children who, having had their homes destroyed in raids, endured an entire exam season despite being without accommodation or spare clothing. Decades earlier The First World War and the Spanish Flu pandemic saw innovation taking place to keep formal assessment on track. Boys and girls were examined together for the first time, and women were allowed to fulfil invigilation roles. The strong desire to carry out exams, come what may, suggests that we see them as a vital part of the natural order of things.

Where the bombs of the Luftwaffe failed, however, Covid-19 succeeded. As it became clear towards the end of March that schools would be closing, attention turned quickly to the cancellation of exams and the thorny question of how qualifications could be awarded without the traditional process. Administrative bodies across the four nations opted for a system of ‘centre assessed grades’, whereby schools submitted estimated grades for students in each subject. The exam boards have been subjecting these grades to a process of moderation to try to ensure a level of fairness in the outcomes and protect against grade inflation.

For a minority of committed progressive folk, this unprecedented situation provided the glimpse of an opportunity. If a teacher-assessed system could be shown to be effective, it could hammer the death nail for the examination-based approach that they view as archaic and oppressive. As Simon Jenkins wrote in The Guardian in May “There are some blessings to Covid-19, and one may yet be to liberate education from the dictatorship of ‘the test’’. The idea that exams are a constricting distraction that obscure the joy of learning has been the focus of recent research which recommends teacher assessment in both the UK and the US.

It would appear that the teacher-assessed model is, however, dying before it has had the chance to be born. The moderation process that was employed in Scotland by the Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) to compensate for apparent grade inflation by schools led to the downgrading of students and affected most those in deprived areas. Following accusations of unfairness and the risk of numerous appeals and contestations, Education Secretary John Swinney yesterday announced that downgraded students would have their results revoked and replaced by the raw teacher-given grades.

Seemingly panicked by this, in a last-minute policy shift, the DfE has announced that downgraded students in England would be able to use previous mock exam results if they exceeded the grade awarded by the exam boards. This eleventh-hour move has been chaotic for schools and its logic has been heavily criticised by school leaders. It is no surprise that exams will be back in October; the sooner the better as far as the authorities are concerned.

Many of the criticisms levelled at exams as a framework for learning and a means of assessment have validity. There have been valiant attempts over the years to provide a balance between formal assessment and coursework-based, teacher-assessed learning, and this trend rightly continues in many vocational and technical courses. However, despite their drawbacks, exams do encourage and promote a much wider set of skills and values than is often acknowledged by their child-centred opponents. And these qualities appear to be important to both students and their parents. Preparing for exams requires prioritisation and planning skills, emotional resilience, self-reliance and discipline. Succeeding in an exam environment requires a cool head under pressure, determination and persistence. And above all, the acquisition and retention of knowledge is viewed as of paramount importance.

What is obvious and striking about these skills and values, is the extent to which they scream social conservatism. It is not hard to see why some progressives may recoil at this system. It hardly seems focused around the values of creativity and individuality that they view as central to their identity. The 2015 British Election Study demonstrated that conservatives were more likely to prioritise attitudes and behaviours within the overall value umbrella of ‘conscientiousness’, which seem a perfect fit for an exam-based education system. Progressives tend to value ‘openness’ which is linked to creativity, and are more prone to ‘neuroticism’ and ‘emotional instability’. It’s not hard to see why the exam hall might be educational kryptonite for them.

So here’s the paradox. Exams seem to fit the bill of a hot culture war issue, particularly in these febrile times. And yet when Michael Gove and Dominic Cummings set about reforming GCSE and A Level qualifications from the Department of Education in 2011, there was little more than a grumble. Opposition seemed to be more focused on the precise content of the History and English curriculum, than the fact that project-based, teacher-assessed components had been reduced to an afterthought. Exams were front and centre again, and more demanding and stress-inducing than before, but there was seemingly very little desire among the most avowedly progressive members of society to seriously challenge the method of our assessment system. Why this is the case is worth some consideration.

To my mind, the answer to this conundrum lies in two places. The first is with a shared concept of justice. Having worked in examinations for a number of years, I have heard exams derided and disparaged in many different ways. They are ‘cruel’, ‘damaging’, ‘joyless’ and ‘tedious’. But I have rarely heard exams called ‘unfair’. Exams provide an impartial and independent judgement on the performance of each student.

Conservatives and indeed many liberals favour them because they appear to conform to a meritocratic standard, and are not prone to corruption or cronyism. Maybe the scope of what they test is limited, but no system is perfect. For progressives, a teacher-assessed system may be more just in egalitarian terms and more inclusive because it does not prioritise such a particular set of skills. Convincing the majority of people that it is robustly meritocratic, would, however, be a huge uphill struggle.

Here the Scottish affair is instructive. Despite its apparent bungling of the matter, SQA was aiming at fairness by trying to bring 2020 attainment into line with previous years. It’s clear that it is not an easy job to create an algorithm that would be rigorously meritocratic in this situation. But one of the reasons formal exams are seen as fair, and many feel the SQA approach was unjust is because the exam system treats each candidate as an individual. There is something morally cold about the collectivism of a general, aggregate moderation process. As Stephen Bush pointed out succinctly “government forgetting life not lived in the aggregate. In aggregate, yes, moderated results are more ‘fair’. But that’s not how it feels to anyone…whose results are downgraded.”

A somewhat more cynical possibility is that there is a second, less noble reason that exams get an easy ride. Those who would be most likely to challenge them on the basis of a more progressive view of education often have little material incentive to do so. There is a reason why constitutional theorist Vernon Bogdanor has labelled the progressive middle-classes the “exam-passing classes“. The writer Nassim Taleb puts it less generously but more colourfully in his most recent book, Skin In The Game, when he talks about the “Intellectual Yet Idiot” who ‘can’t find a coconut on Coconut Island…their main skill is to pass exams written by people like them’. In other words, exams provide a veneer of meritocratic justice which is useful to those who benefit from them materially the most.

It is not unusual in the Anglosphere for the progressively-minded to quietly practise values and lifestyles that are very different to what they preach, as Ed West argued in UnHerd. “Think progressive, live conservative” or “social liberalism for thee but not for me” is a common hypocrisy. In their approach to their children’s education and accomplishments, progressive middle-class parents often employ a Hobbesian ethic whereby stability and security are viewed as the indispensable precondition of individual flourishing. Exams provide a good structure for this via the socially conservative norms and behaviours they promote. They also have the added bonus that they can be justified to oneself in moral terms, in a way that coursework and teacher-assessed systems can’t. A well-defined meritocratic framework allows those at the top to believe that they are deserving of their success, while viewing those at the bottom with less sympathy. Progressive valorisation of child-centred learning and pedagogical experimentation then becomes something that is largely for show, a way of acquiring status among the in-group.

In the end it appears that exams are going to survive Covid-19 relatively unscathed, as they have survived threats in the past. Our commitment to exams appears unshakeable. This is partly because, as Winston Churchill said of democracy, they are the worst form of assessment apart from all the others. But it is also because those who, given this unique opportunity, might have been expected to challenge the status quo hardest are also those who are wisest to its benefits.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe