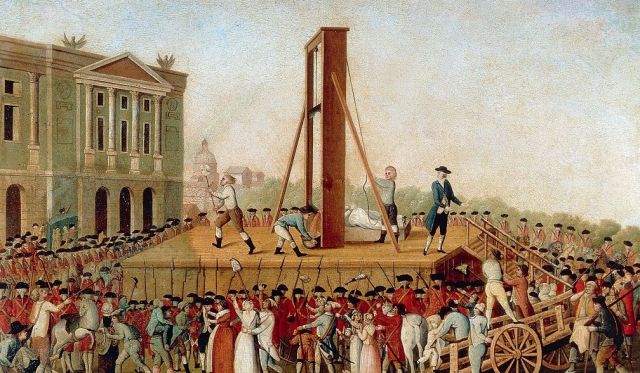

Where it all went wrong. Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images

It has recently become common to invoke a Jacobin parallel for the current state of the Left in America. A few guillotines have indeed appeared, as props in the theatre of protest. But they have been miniatures made of cardboard. Conservatives run the risk of melodrama – their own theatre of protest – when they invoke a woke Terror.

Still, study of the French Revolution is endlessly instructive, for the radical temptation in politics exhibits consistent patterns, and the French Revolution displays them in crystalline form. Here are a few historical works on the period that are beautifully written, and may prove helpful for understanding the present.

François Furet, Interpreting the French Revolution (1978) and The Passing of an Illusion (1995)

François Furet rescued the academic study of the French Revolution from an entanglement with Marxism that had grown debilitating in the decades after World War II. French historiographers of that period tended to project backwards onto Robespierre all the romance of 1917, and likewise to view the Soviet Union as the successor state chosen by History to advance the cause. What made this no longer tenable was the publication, in 1973, of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago. The very parallels insisted upon by Marxist historians were now damning to their enthusiasms. Just as Solzhenitsyn showed that the gulag was no mere accessory to the revolutionary state, but rather its central manifestation and meaning, so it now became necessary to ask whether the Terror was not just a regrettable episode to be excused by extenuating circumstances, but the most revealing expression of revolution as a political culture.

This question had implications for how one was to understand the revolutionary passions of the youth movement of the 1960s, and Furet did not shy from drawing the relevant lessons. A member of the French Communist party in his youth, he came to see things in rather a different light. The opening essay in Furet’s Interpreting the French Revolution offers many riches. For example, he explains the paranoid style of revolutionary politics, and its tendency to exercise power through contrived moral emergencies.

Furet’s final book, The Passing of an Illusion , traced the revolutionary passion in its career through 20th-century intellectual life in the West. Writing in the early Nineties, when Communism had just collapsed, the choice of title must have seemed apt to book buyers. But Furet knew that “the revolution” is infinitely elastic, so boundless is its promise and so limitless is its “capacity to survive experience”. It has a birth date (1789) but no end; it provides “the matrix of universal history”. That history is understood as a struggle of human emancipation, its polestar a vision of equality. Whatever stands in its way appears not as mere obstacle, but as hateful enemy.

Simon Schama, Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution (1989)

In the 1780s, the highest reaches of French society, as well as the broader reading public, was infatuated with the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Far more influential than his works of political philosophy were his works of sentimental education, Emile and the Nouvelle Héloïse. As Simon Schama wrote, “Rousseau’s works dealing with personal virtue and the morality of social relations sharpened distaste for the status quo and defined a new allegiance. He created, in fact, a community of young believers.” Rousseau gave no roadmap to revolution, but he did invent “the idiom in which its discontents would be voiced and its goals articulated.”

What distinguished the moral elect was possession of un coeur sensible, a feeling heart. Visible expression of inner sentiments became acceptable, and indeed to be overcome with passion was a sign of noble character. Weeping was a sign, not of weakness, but of sincerity. Schama writes that tears “were cherished precisely because (it was assumed) they were unstoppable: the soul directly irrigating the countenance. Tears were the enemy of cosmetics and the saboteur of polite disguise. Most important, a good fit of crying indicated that the child had been miraculously preserved within the man or woman.” Note the role of self-exposure in creating a moral typology of citizens. Soon, sincerity would become the virtue claimed by axe-wielding sans-culottes.

Reading Schama’s account of weeping French men and women before the Revolution, one cannot help but think of today’s emotivism, in which feeling replaces intellectual coherence as the index of truth. That is, of one’s own truth, which others must acknowledge and acquiesce to – or else wound one deeply. On Twitter, of course, tears are not visible. “I’m literally shaking” is a verbal embellishment that seems to serve the same purpose. It conveys intensity of feeling, hence the moral credibility of one’s response.

Mona Ozouf, “Revolutionary Religion”, in A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution (1989)

In 2020, shrines to George Floyd sprang up in cities across America, with candles set before garlanded pictures of the man (as in a Hindu temple). An enormous holographic effigy of Floyd went on tour through the southern states. We have all seen the videos of white people washing the feet of black people, in emulation of Christ’s servanthood, and prostrating themselves in various postures of abasement while chanting self-denunciations.

In Robespierre’s Festival of the Supreme Being, explicitly religious props, recitations and images were used to imbue revolutionary ideology with sacred feeling in a deliberate caricature of Catholic ceremonies. “Here there were not spectators but celebrants, not an audience but a people,” as the historian Mona Ozouf wrote. The Festival was preceded by the destruction of France’s statues by “iconoclastic commandos from the revolutionary army”. The heart of Marat (one of the bloodier Jacobins, himself stabbed to death in his bathtub by a provincial woman) was placed in a vessel and hung from the roof of the Cordeliers as the crowd was encouraged to recite new psalms (“O cor Marat, O cor Jesus”). The Festival coincided with a busy period for the guillotine, as intended by Robespierre.

Was the revolutionary cult a strategic ruse, then, meant to reconcile the Revolution with Catholic habits through a superficial continuity? Perhaps it was an effort to bring the Revolution to a conclusion by establishing a state religion, in the hope that this would help to secure social cohesion? Historians disagree on these questions, and Ozouf guides us through the controversies.

Contemporary America is about as far from Catholic France as it is possible to get. Religious longings, apparently a permanent part of our human makeup, have long been frustrated in our secularised society. But for just that reason, revolutionary piety may hold special appeal. This bears on a question that has long hovered over the phenomenon of “political correctness”: how sincere is it? And is the quotient of sincerity changing?

Writing in The Atlantic in 2018, which now seems a long time ago, Reihan Salam parsed the utility of “white bashing” as part of the verbal repertoire of success in elite institutions. In this setting it was generally ironic, even while doing important work to signal that one is competent in the codes of the ruling class. “The people I’ve heard archly denounce whites have for the most part been upwardly-mobile people who’ve proven pretty adept at navigating elite, predominantly white spaces.” Salam, a child of Bangladeshi Muslims and Harvard student, came to view white-bashing as a form of “intra-white status jockeying,” a device by which the demarcation between “upper whites” and “lower whites” is made clear.

It would be hard to fix a date, but at some point this parlor game slipped the bounds of its intended audience. In the hands of the vulgar, it became literal-minded rather than playful, moralistic rather than urbane, a way of mobilising resentments and putting them to use. Again, one thinks of the trickle-down radicalism in France of the 1780s, as depicted by Simon Schama. The elite’s fashions of sentiment, its internecine dramas that seemed to be playing out in a safely “cultural” register, would become the seed of something more ominous. Something unintended and uncontrollable.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe