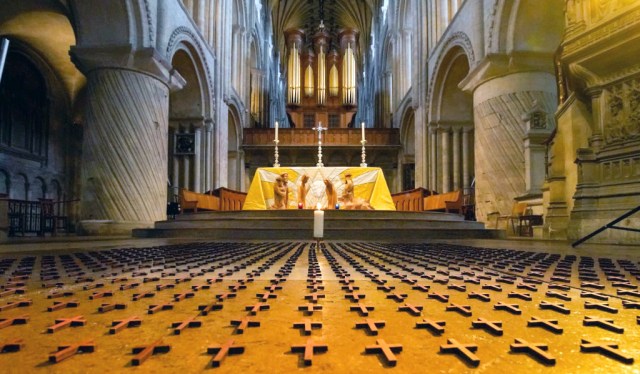

A memorial to Norfolk’s Covid dead in Norwich Cathedral. Christopher Furlong/Getty Images

Henry VIII not being able to keep his pants on is the best-known C of E birth narrative. But there is another, more edifying story. Because of Henry’s zipper trouble, the Church in England eventually stumbled into a hodgepodge religious compromise that allowed a place for very different and hitherto warring theological instincts peacefully to co-exist. Semi-peacefully, at least.

It didn’t happen by design. And a horrendous religious civil war was to follow, an extension, in many ways, of the wars of religious that had disfigured Europe with Protestants and Catholics all slaughtering each other in the name of God. But, in this country, a place of healing was eventually discovered. In this place, faith began to be separated from violence.

That place was the parish church of the Church of England. Here, both the catholic and the protestant instincts could be partially accommodated. This was somewhere people could worship in the same church without reaching for the pitchforks. Divisions could be managed without necessarily being overcome. With a book of common prayer — the common bit being crucial — and an emphasis on prayer and pastoral care, the established church, and the parish church in particular, became the site of national healing.

Not for everyone — non-conformists, for instance, were side-lined. But what held a great many people together was a loyalty to the local, to place. And more than any other institution, the parish church symbolised this renewal of local solidarity. Former enemies could sit alongside each other in church and pray to the same God, bracketing out their ideological differences, suspicious of enthusiasm, both catholic and reformed, singing over the cracks.

Lulled by sandy stone architecture, the gentle lullabies of “Dear Lord and Father of Mankind, forgive our foolish ways”, and an irenic, softly spoken Vicar, the parish church did its job almost too well. The English church fell asleep.

But for all its many dangers, enthusiasm also has its uses — not least when the church urgently needs to rally its forces in the face of a growing lack of interest, as it does right now. For all its many virtues, the gentle sleepy spirit of the parish church doesn’t always feel like a bridgehead for the re-conversion of England. Passion needs to be re-kindled. Forces need to be concentrated. The Christian church within England has to return to missionary mode. And it is, therefore, perhaps inevitable that some of us parish clergy are feeling a little bit of whiplash. Times they are a changing.

But many of the problems we now face are as much the consequence of missionary over-reach as of sleepy church complacency. The year I was ordained, the sociologist Robin Gill published his famous The Myth of the Empty Church, which should have probably been titled The Myth of the Full Church. The Victorians built too many churches, he argued, thus burdening and bankrupting future generations with the upkeep of impressive but expensive God boxes. It was the boom-and-bust theory of church growth.

The history of my ancient parish bears this out: Newington dates back to 1212, perhaps even earlier. Geographically, it was huge by modern standards, covering an area now served by a dozen or so parishes, most of what we now call Southwark. When London expanded during the 19th century — from a population of 1.9 million 1810 to 6.2 million in 1897 — the Church of England responded with a massive programme of church building. In the middle of that century, a new church was consecrated every four or five days. My own parish was split into ten between 1826 and 1877. And there were more later, carved from parts of my old parish and slices of neighbouring ones.

These were the boom times, built at the height of imperial confidence. But bust is now upon us. This week we had to go cap in hand to the Diocese to ask them for a loan. Our old Victorian church hall collapsed back in December and the bill for demolition is around £150,000. We have nothing like that.

This week we also learned that the Church is concerned about “the sustainability of many local churches” — a problem floated in a leaked document. The Covid crisis has cost the church something in the region of £150 million and counting. And there are those who say that many of our congregations will never come back. As the report detailed: “Church attendance has reduced by around 40% over the last thirty years; the number of church buildings has fallen by 6%, which means a higher cost burden for the remaining attendees.” Something has to give. I cannot keep on asking my parishioners for money they don’t have. And the Diocese is no longer able to keep on subsidising all those churches that do not pay their own way.

But if the Church of England is to be precisely that – a church for the whole of the country, rich and poor — it cannot retreat into the wealthy suburbs, leaving the inner-city churches to become repurposed as designer flats with pointy ceilings. Nor can it fool itself that Zoom is the magical answer – a way of providing church without the need to worry about the leaky roof or whether or not we can afford to turn on the heating. Zoom has its advantages, not least that it offers to the housebound a window into the worshiping life of the church they are no longer able to attend. And indeed, over the last year, my own congregation has grown by about 20%, with new people joining us from all over the world. But for those churches in the more Catholic tradition, where church life centres around the offering of bread and wine, zoom is no substitute.

Transubstantiation may be an unexplainable miracle, but there is no way to convert the body of Christ into a digital offering that can be passed into the hands of the congregation via the camera on my laptop. You can no more offer the body and blood of Christ over zoom as you can go to the dentist over zoom. Catholic Christianity is inescapably physical, incarnational. And Zoom is, so to speak, an inherently Protestant medium, a genius technology for the promulgation of the word (much as the printing press did so much to accelerate the Reformation) but incapable of carrying the full weight of a more catholic sensibility, with its emphasis on place and presence. An evangelical church can function more like Boohoo than Debenhams, but a catholic one cannot.

It is not the fault of the more successful parts of the church that the poorer parts of it are struggling. And it is a mistake to look at the growth of the more missionary minded evangelical parishes and regard them as some sort of threat to parishes like mine. Nonetheless, the idea that precious resources should be redirected towards growing, successful parishes does nothing to address the question of how the Church of England survives within the inner city. Such an approach would transform the Church of England into a middle-class broadly Protestant offering, and thus constitute a retreat from the core Church of England raison d’etre of, as it were, universal service provision. The only good justification for an established church is that it has a presence within every community in the land. Without this, disestablishment would be morally unavoidable.

One way to both save the parish and allow the release of missionary energy would be to cut the layers of middle management that Dioceses haves built up over time. The Henry VIII shaped problem that the Church of England has is that of the bloated middle, with the continual invention of administrative jobs located at Church House. Some of us who are struggling to keep our parishes going unkindly wonder whether there are too many people employed by the church to sit behind a desk rather than stand behind an altar. We may also need to cut the number of Dioceses and expensive talking shops like the General Synod. But the truth is that without the central structures of the church, parishes like mine would no longer exist. After all, from where else would we get a loan from to pay for the demolition of our church hall? Indeed, how else could the parish afford to have a priest here, and a Rectory, if not for the subsidy administered by Church House.

But do these central structures really need to be so big? Church house for the Oxford diocese now employs more than 100 people. These are jobs that are replicated in many of our 42 dioceses. The Roman Catholic church, for example, seems to be able to manage (just as successfully) with a few office staff and an old filing cabinet. The problem within the Church of England appears to be the employment of a whole middle management class of communication officers and compliance professionals generating reams of forms and paperwork. In normal times there may be a case for such work. But when the church is busy cutting frontline staff — the parish clergy — the existence of this bloated middle has to be seriously challenged.

But if we’re talking about greater subsidiarity, this inevitably means parishes taking greater responsibility for their own financial affairs. At the moment, and however much I explain otherwise, many in my parish still believe that we pay some sort of tax to the diocese just for existing. In truth we are heavily subsidised. It is the worst of both worlds.

So yes, the church must change. There will be much pain in those changes for many. But what, for me, is absolutely non-negotiable is the parish system. Parishes like mine covered a much larger geographical area before and they can do so again. Some churches will close. Some of that hubristic Victorian over expansion will have to be reversed. Resources must be concentrated. But the idea of a priest in a parish must be defended. The transformation that is needed will not take place successfully if the parish clergy fear that the central church regards its poorer parishes as little more than failing cost centres.

This is a crucial moment for the C of E. But churches have survived much worse. And events of the 21st century have demonstrated that the old narrative of slow religious decline is as much a myth as that of that of the Victorian church triumphant. Globally, Christianity continues to grow in the most unexpected places. China, for instance. But on these shores, we are called to be faithful in dark and difficult times. The Christian faith contains a genius for reinvention. And if we are right that God is in his heaven, then there is ultimately nothing to worry about. And if we are wrong, then it doesn’t matter anyway.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe