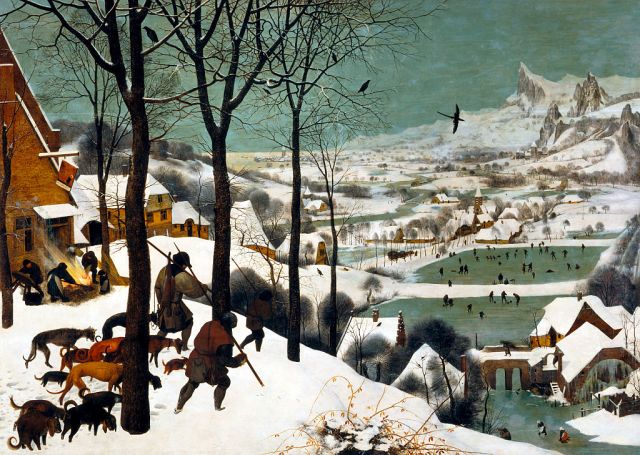

Our ancestors were inventive in the face of crisis. Can we be, too? Credit: VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images

The severe winter of February 2021 left Texas, Oklahoma, and Mississippi in blackout. At temperatures of -18 degrees centigrade, millions of people were left without power or running water. Alice Hill, a former risk assessor for the National Security Council under Obama, warned, “we are colliding with a future of extremes … the past … is no longer a safe guide.”

She was probably thinking of the recent past — the few centuries in which meteorological records have been kept. Figuring out past weather before that takes an ingenious combination of history, archaeology and science: eye-witness accounts and fluctuating grain prices are married with data from ice cores, grape-harvest dates and tree-ring sequences. But that tricky evidence indicates past climatic extremes that could provide “predictive points of reference for adaptation and loss reduction,” as Oliver Wetter, Jean-Laurent Spring et al argued in the science journal Climatic Change in 2014 (in a nice case of nominative determinism).

This evidence points to a Little Ice Age from around 1560. Winters were severe. Pieter Bruegel painted his hunters, their heads bent against the cold, trudging through deep snow towards villagers skating on a frozen river. But the Little Ice Age wasn’t just a deep freeze. It was also a “climatic seesaw”, writes Brian Fagan, of “arctic winters, blazing summers, serious droughts, torrential rain”. A winter storm in summer and a tropical hurricane at an unusual high latitude thrashed the Spanish Armada of 1588 far more roundly than the English warships.

One great drought predates the start of the Little Ice Age by 20 years. In February 1540 rainfall effectively ceased, falling only six times in London between then and September. It was not only exceptionally dry but warm: it is probable that the highest daily temperatures were warmer than 2003 (the warmest year for centuries). Charles Wriothesley’s Chronicle notes,

“This year was a hot summer and dry, so that no rain fell from June till eight days after Michaelmas [29 September], so that in divers parts of this realm the people carried their cattle six or seven miles to water them, and also much cattle died; and also there reigned strange sickness among the people in this realm, as laskes [dysentery] and hot agues, and also pestilence, whereof many people died…”

Edward Hall noted that the drought dried up wells and small rivers, while the Thames was so shallow that “saltwater flowed above London Bridge”, polluting the water supply and contributing to the dysentery and cholera, which killed people in their thousands. In Rome, no rain fell in nine months; in Paris, the Seine ran dry. Grapes withered on the vine and fruit rotted on trees. Even the small respite of autumn and winter was followed by a second warm spring and another blisteringly hot summer. Forests began to die until, in late 1541, rain fell and fell. 1542 was a year of widespread flooding.

It is reductive to argue a simple causative relationship between the climate and historical events, but it is equally false to suggest the weather had no effect at all. Excessive heat only needed to affect the judgement of one man, Henry VIII, to create deaths. In July 1540 the visiting French ambassador described as the “extraordinary sight” of three Catholics being hanged for treason and three Protestants burnt for heresy in Smithfield in London on the same day. A week later — Henry’s right-hand-man, Cromwell, being beheaded on the day that the aging king married a teenager. Maybe the king’s famous temper was worse when he had a sweat on him.

The effects of the great drought were less far-reaching, however, than the devastating conditions of the 1590s. Rain fell across Europe for the best part of four years, while mean winter temperatures dropped two degrees. Titania in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, describes it thus:

“…the winds, piping to us to vain,

As in revenge have suck’d up from the sea

Contagious fogs; which, falling in the land,

Hath every pelting river made so proud

That they have overborne their continents.

The ox hath therefore stretch’d his yoke in vain,

The ploughman lost his sweat, and the green corn

Hath rotted ere his youth attain’d a beard.”

Freezing rain meant the harvests of 1593, 1594, 1596 and 1597 failed. It’s hard to grasp what this meant in an age of subsistence farming; we can know there were no supermarkets and still fail to comprehend what it must have been like to live without any cushion against starvation. One harvest failure meant hunger; two in a row, dearth; a run of bad harvests, famine. Fear gripped as tightly as cold. Epidemics followed in famine’s wake. Prices rose to 40-year highs and, as Bob Marley sang, “A hungry mob is an angry mob.”

People rose up and authorities clamped down. On 13 June 1595, a crowd of three hundred apprentices protested the price of butter in Southwark market by seizing control and forcing vendors to sale at the old, lower price of 3d. a pound. A fortnight later, some of these apprentices were publicly whipped and set on the pillory, which itself instigated a riot. A thousand-strong crowd marched on Tower Hill, planning to “steal, pill[age] and spoil the wealthy … and take the sword of authority from the magistrates and governors.”

Food scarcity had quickly morphed into class hatred. Five of the apprentices were hanged for treason. Over the next year, there were attempted risings in Oxfordshire, Devon and elsewhere, while a Somerset JP observed to Lord Burghley that inequalities were worsening: “the rich men have gotten all into their hands and will starve the poor.”

Years of hardship make some people richer and some people poorer or, more exactly, they make the rich richer and the poor poorer. Plus ça change. In the coronavirus pandemic, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg and Zoom founder Eric Yuan have increased their already gargantuan fortunes by several billions of dollars. In the UK, all that was required to make a profit out of other people’s pain was, apparently, to be chums with a Conservative. (The New York Times found in December that some $11 billion of UK central government contracts went to companies run by associates of the Tories, or with no prior experience or a history of fraud, corruption or other controversy. And that’s just the data that has been published.)

History has more to tell us on this. It was so cold in the terrible winter of 1607-8 that the trunks of large trees split open, and the Thames froze so solidly that people sold beer and played football on it: the first Frost Fair. The “Great Frost”, as an anonymous writer – maybe Thomas Dekker — called it in 1608, made the Thames “bankrupt”. London was cut off from commerce that relied on the river. Furloughed Londoners called it “the dead vacation”, for, Dekker wrote, “if it be a gentleman’s life to live idly and do nothing, how many poor artificers [artisans] and tradesmen have been made gentlemen then by this frost?”

Merchants could not ship goods, and neither wood nor coal could reach London. The price of fuel rose without mercy. Things were hardly better in the country: “the poor ploughman’s children sit crying and blowing their nails”, while “the ox stands bellowing, the ragged sheep bleating, the poor lamb shivering and starving to death.”

These recurrent moments of climatic crisis did not just leave people cold and hungry. Many poorer families went continually into debt, forcing all members to work as many jobs as possible in the “economy of makeshifts”. Neighbourly relations were tested by the moral customs of hospitality and charity and the necessity of thrift and self-preservation. The witchcraft craze of the late sixteenth to mid-seventeenth centuries, in which perhaps 45,000 died, was exacerbated by deep insecurity and resentment. Hunger, envy and anger created the mental space in which witchcraft accusations occurred.

The trigger for accusing a neighbour of witchcraft was often linked in some way to food and fertility — the death of the cow or the sale of a pig — some vital livestock that meant the difference between having enough and not. The institutional response to poverty was to introduce relief for the poor, but with moral judgements attached. The pernicious conceptual divide between the deserving and undeserving poor — those unable to work and those thought unwilling to work — remains with us. It was thought that beggars and vagabonds chose to be unemployed when in fact opportunities were contracting. The Vagrancy Act of 1597 ordered the punishment of “all wandering persons… able in body, loitering and refusing to work” by flogging, branding, transportation overseas, or confinement to gaol-like houses of correction that prefigured later workhouses and modern prisons.

What can we learn from these grim years? Most obviously, the slowly unfolding disaster of global warming means extreme weather events will be more common. We might not starve from harvest failure, but excess rain can make raw sewage overflow into homes and roads collapse — like the spectacular Highway 1 in California. Electricity grids can be knocked out by frosts or heatwaves; deep droughts reduce water supplies. “Present bias” makes it hard for us, writes Henry Fountain, to make the lifestyle changes that could prevent or mitigate catastrophe down the road, but the past and the future are begging us to do so.

But these extreme events also speak much to us after a year of lockdown. The inequalities between rich and poor have become stark and, like the “prentices” in Southwark, those who can least afford it are the worst hit. Those who have been made redundant or whose hours have been cut or who don’t know if they’ll have a job after Covid endure the gnawing anxiety, shame, and misery that money worries bring. But the deep insecurity created by furlough, job losses and ravaged self-employment is also emerging in other ways.

This has been a year of stresses and distresses which, coupled with the sheer insularity of lockdown, has exacerbated tensions between groups, producing a sense of feeling aggrieved and that certain disputes are irreconcilable. We are all under strain; trust is eroded. We look to provide for ourselves; we are quick to judge others. We may not accuse our neighbours of witchcraft, but we have our modern equivalents. If there is a cultural war, the deprivations of 2020-21 will have aggravated antagonisms. Even familiar bonds have been challenged by obedience (and disobedience) to lockdown rules.

Our forebears were inventive. They found new ways to survive in the face of unpredictable weather: they adopted new foods, like root vegetables and pulses, planted new crops, and used new methods for farming and preserving. In Austria, the cold gave the wine such low sugar content that much of the population switched to beer drinking. But, as the author of The Great Frost noted, “these extraordinary fevers have always other evils attending upon them”. We must be scholars of time and harken to the lessons she would teach us.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe