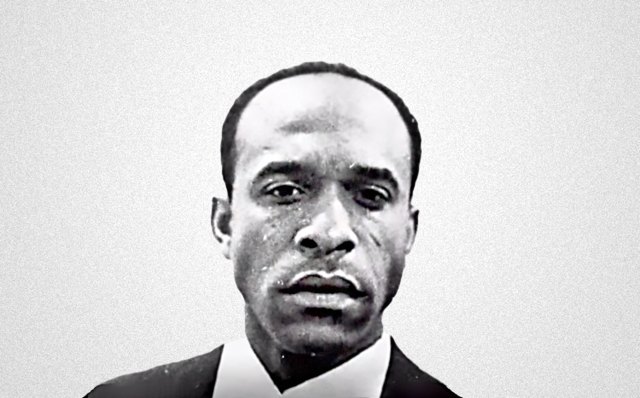

Fanon was animated by a deep curiosity (Still from “Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask”)

The Black Panther activist Eldrige Cleaver once claimed “every brother on a roof top” could quote Frantz Fanon. Another Black Power leader called him one of his “patron saints”. And you could see why: a prophet of the Third World revolution who fought for the wretched of the earth, and whose life ended before he turned 40. But St. Frantz is a mirage. As his biographer David Macey puts it: “there were other Frantz Fanons”, apart from his status as a prophet of Third World revolution.

On the very first page of Black Skin, White Masks — which has just been published as a Penguin Modern Classic, using Richard Philcox’s translation — Fanon states: “I’m not the bearer of absolute truths”. Which doesn’t sound very saintly. He was trying to emphasise his humanity instead of being seen solely for his race. The book is an investigation into neurosis and alienation; the crisis of a man who thought he was just a man, but discovers instead he is a nègre. “Look Mummy, a nègre,” a little child says and points to Fanon.

The text is often dense: Fanon mixes literary analysis of obscure novels with the jargon of phenomenology. He can be horny, sad, angry, introspective and playful — all on the same page. The sections that seem to be influenced by Hegel are particularly tough work. It is not entirely surprising that the book was a damp squib on publication. No major French newspaper or journal reviewed it; by the time Fanon died from leukaemia, at the age of 36 in a hospital in America, it had been out of print for many years.

Fanon did have aspirations to be a playwright. And the drama involved in the text is positively theatrical. He didn’t type the manuscript himself, but rather dictated it to his inamorata, Josie; this explains the sudden shifts in register and tone. This is not a contained book; it bursts with the energy of a young man.

Fanon was 27 when it was published, a Jacques the Lad who loved football, and as a teenager stole marbles and snuck illegally into cinemas with his friends. In a letter he sent to a friend about the book, which is quoted in Macey’s biography, he affirms: “I am trying to touch my reader affectively, or in other words irrationally, almost sensually. For me, words have a charge. I find myself incapable of escaping the bite of a word, the vertigo of a question mark.”

Another reason why Fanon can be called a saint was his strident moral universalism; but this universalism can be explained, at least partly, by his background as a black man from the French West Indies. As he puts it in the introduction to Black Skin, White Masks: “As those of Antillean, our observations and conclusions are valid only for the French Antilles”. The rest of the book is, indeed, very French.

Fanon was born to a middle-class family in the French West Indian colony of Martinique. His father was a civil servant and his mother a successful shop owner. The family were so well-off they could afford servants. They even owned a second house in the outer suburbs of Fort-de-France, the capital city. Martinique was an old colony: many of its institutions, such as its schools and courts, were modelled on metropolitan France. Fanon attended a fee-paying lycée, a privilege that poor West Indian blacks couldn’t afford — neither could poor whites in France.

One might think, on knowing that a white population lived in Martinique, that they were the emissaries of mainland France. They would be wrong. The Békés — as the Martinique-born white population was called — were opposed to Martinique being integrated as a French territory in 1946, and they supported the Vichy regime during the second world war,

They were a clannish, endogamous minority composed of landowning families. Interracial marriage here, unlike in metropolitan France, was completely taboo. In a documentary by Stuart Hall on the nations of the Caribbean, an elder Béké man, with a grin on his face, compared them to the mafia. They lived in a hill just above Fort-de-France: there was a rivalry between the landowning Békés and the rising urban black and mixed-race middle-class families in the capital city.

Fanon’s life was in many ways not just an embrace of republican France, but a rejection of the lifestyle and beliefs of Békés. He fought for de Gaulle’s Free France, and was decorated with a Croix de Guerre. He married a white woman. And, at a deeper level, his commitment to republican French universalism — which, of course, wasn’t fully practised in France, as he later found out when he moved there to study medicine — was in stark contrast to the American-style racial obsessions of the Békés in Martinique.

Fanon, in his book, is trying to affirm the universal brotherhood of man. In one passage, he states: “we must recall our aim is to enable better relations between Blacks and Whites”. It is no surprise, then, he is sensitive about anti-Semitism: “Anti-Semitism cuts me to the quick,” he writes. “They are denying me the right to be a man. I cannot dissociate myself from the fate reserved for my brother.”

He rejects being viewed as black person. He wants to be seen simply as a person: “The black man, however sincere, is a slave to the past. But I am a man, and in this sense the Peloponnesian War is as much mine as the invention of the Compass.” Later he lyrically adds: “It is not the black world that governs my behaviour. My black skin is not a repository for specific values. The starry sky that left Kant in awe has long revealed its secrets to me.”

Unlike many self-described anti-racists today, who engage in performative demands for white guilt, Fanon states: “I have not the right as a man of colour to wish for a guilt complex to crystallise in the white man regarding the past of my race”. What he wants, instead, is respect and dignity: “I, a man of colour, want but one thing. May man never be instrumentalised. May the subjugation of man by man — that is to say, me by another — cease. May I be able to discover and desire man wherever he may be”.

Yet Fanon is also often linked with the Négritude movement, a group of black Francophone intellectuals who wanted to cultivate a distinctively black consciousness. This is partly because the most famous Négritude intellectual was the poet and politician Aime Cesaire, who was not only a fellow Martiniquan, but also taught Fanon at the Lycée Schoelcher. However, Fanon was largely ambivalent to the Négritude movement, and in Black Skin, White Masks he expresses views that run contrary to their ethos: “In no way do I have to dedicate myself to reviving a black civilisation unjustly ignored. I will not make myself the man of any past”. And he later states: “No, I have not the right to be black. It is not my duty to be this or that”.

What animates Fanon most was a deep curiosity. In the book’s conclusion, he asks: “Superiority? Inferiority? Why not simply try to touch the other, feel the other, discover each other?” Indeed, the final sentence is: “My final prayer: O my body, always make me a man who questions.” And so explicitly linking Fanon to his French colonial background has its pitfalls; it potentially blunts his wish to be free from his past, and to be, as he put it, “constantly creating myself”.

But while his background didn’t determine his views and attitude, it did, to a considerable extent, influence it. What can be more French — apart from the obvious things — than turning the act of asking questions into something sacred? On the front cover of the new edition of Black Skin, White Masks is a photograph of Fanon. He looks both proud and sceptical, embodying the most captivating features of French culture.

If Fanon was an icon of anything, it wouldn’t be Third World revolution, but rather republican France. But he was not an icon; he was simply a man. And his humanity was all the more transparent in the tragic gap between his universalist ideals and the reality of being seen as just a nègre.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe