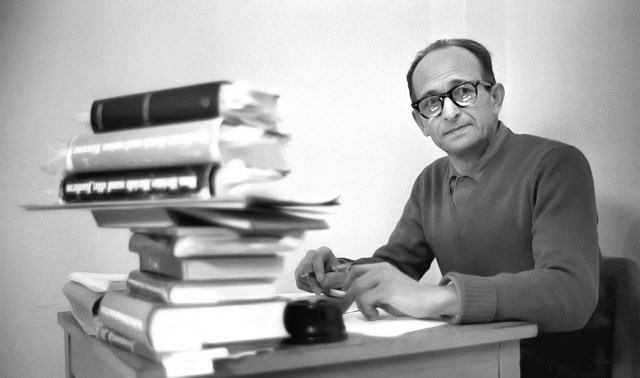

He was a monster. (Photo By Gpo/Getty Images)

On April 6, 1941, just four days after my fifth birthday, I heard Hitler’s name for the first time. Germany had suddenly invaded Yugoslavia and the Luftwaffe had started to bomb our neighbourhood in Belgrade. Amid the sound of explosives ripping through nearby buildings, our family sheltered in the basement laundry room of our reinforced concrete-built house. And then a bomb found its home — exactly where ours used to be.

My grandmother fell on me to protect me; then, when she was hit by the room’s door, blown off its hinges, she cursed and used Hitler’s name. We were lucky; in the adjacent basement several of our neighbours were killed. Somehow, we were not.

It was only while I was a refugee in Budapest that I learned Hitler’s first name: Adolf. Then, at some point between the entrance of German troops into Hungary in March 1944 and my deportation aged eight that summer to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, I added to my vocabulary the name Eichmann. At the time, it was just one name among many others. Little did I know that almost 60 years ago to the day, I would stare him directly in the face as he stood trial for helping to organise one of the darkest chapters in mankind’s history.

After the termination of the war, and our return to Belgrade to search for relatives who had survived, I learned from my mother’s cousin the words Auschwitz, Birkenau, Mauthausen and Dachau. She had been deported to Auschwitz, but, being young and healthy, was spared the Gas Chamber and assigned to a bloc where prisoners’ items were sorted. There she found the luggage of my maternal grandparents, allowing us to know the exact day in which they were killed.

In 1948, following the end of the British Mandate over Palestine and the establishment of the State of Israel, what remained of my family immigrated from Yugoslavia. Within a very short period Israel’s population more than tripled in size, largely thanks to the influx of Holocaust survivors. But for some unclear reason, nobody spoke about what they had seen.

People, especially the young, tried to integrate with and mimic those who had been born in Israel, the “Sabres”. What we had been through didn’t seem to matter. At school, for instance, everybody in my class knew that I was the only Holocaust survivor — yet nobody ever asked me what I had gone through during the war years. Enforced reticence was standard, and it continued during my compulsory military service and academic studies.

Even within families, there were two types of behaviour: absolute silence, where children and spouses never heard the tragic stories of the Holocaust experiences; and families like mine, where we discussed our experiences at every meeting. It meant I knew the survival and death story of every family member, but never mentioned them to anyone else.

But then, with the Eichmann trial, everything changed. At once, everybody wanted to talk about the Holocaust; the survivors opened up, and their stories started to flow.

The trial was held in Beit Ha’am, the major arts centre in Jerusalem, and broadcast daily for hours on the two existing radio stations. There were pages and pages of reporting each day in the newspapers. Overnight, that unwritten taboo of speaking on personal Holocaust history disappeared. Just as the number of Holocaust survivors was starting to dwindle, the term “Holocaust Survivor” became a term of praise.

You could order in advance an entry ticket to the trial, if you wanted to just to sit and listen. During the first weeks it was almost completely booked out. I managed twice to get a ticket. My late wife, who had survived Kristallnacht, visited just once. That was all she needed to conclude that before us was a monster.

Eichmann sat motionless in his glass cubicle. On occasion he would answer “Ja” or “Nein” without any flicker of emotion. On the few occasions that he gave a more detailed response, it was to merely explain how he was just a small unimportant clerk who had followed orders.

What did we think of this defence? Well, suffice it to say that for his execution — the first and last in the state of Israel — hundreds of Israelis volunteered to be the hangman. Hannah Arendt may have concluded he was proof of the “banality of evil”. We, however, did not. He was an evil man who oversaw evil deeds — and that, I suspect, is how he will always be remembered.

Certainly, his trial is remembered in the way Israel sees itself today. Perhaps more than anything else, it forged the notion of “Never Again” into our national consciousness; an attitude which the world has learned to accept.

So when Israel decided to punish the plotters and the executors of the terrorist attack on the Israeli Olympic team at the 1972 Munich Olympic Games, when 11 Israelis were murdered by Palestinian assassins, most of the world accepted the rounding up and punishment of those behind the atrocity.

At the time, I was an Olympic racewalker — and one of the six surviving members of the team who did not return home in a coffin. That was, I am convinced, a matter of luck. The apartment I was staying in — between two others that were attacked — also housed two members of Israel’s shooting team. The terrorists probably knew this and avoided our apartment for fear of facing armed resistance. Either way, Evil had come looking for me a second time — and missed me again.

This time round, though, courtesy of Eichmann, the playbook had been written. We knew how to respond. In 1978, when Mossad finally located Ali Hassan Salameh — the mastermind of the Munich massacre — Israel didn’t think twice about making sure the terrorist joined his forefathers. Eichmann had unified and emboldened us. “Never again,” was our response.

Last month, during a Passover dinner, I asked the children around the table if they knew who Eichmann was; of course, unlike me when I was their age, they all did. And that is perhaps the most important result of the trial. Just as Jews have been remembering Moses’s exodus from Egypt for over 3,000 years, Eichmann — and the Evil he represented — will never be forgotten.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe