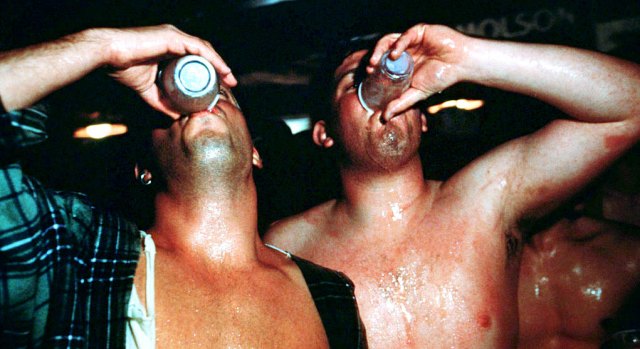

Two men sampling a bottle Château Margaux 1848 (Photo by © Andrew Lichtenstein/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

When Friedrich Engels, the original champagne socialist, was asked his definition of happiness, he replied: “Château Margaux 1848”. Pubs reopen today; and while a bottle of Château Margaux 1848 might be hard to come by, there’s something fitting about the fact that social drinking, as part of the first significant expansion of lockdown freedom, remains closely associated with greater happiness.

Similarly, when we think of historical opposition to the public consumption of alcohol, temperance and prohibition inevitably come to mind — the very opposite of happiness. The people behind these movements, we assume, were rural, reactionary busybodies who hated fun. They were also probably racist. And they definitely had no sense of humour. They were people you wouldn’t want to have a drink with because they wouldn’t want to have a drink with anyone.

Richard Hoftstadter, the influential American mid-twentieth century historian, eloquently expands this characterisation. “Prohibition,” he wrote, was “a pinched, parochial substitute for reform which had a widespread appeal to a certain type of crusading mind”. He describes this “crusading mind” as “linked not merely to an aversion to drunkenness and to the evils that accompanied it, but to the immigrant drinking masses, to the pleasures and amenities of city life, and to the well-to-do classes and cultivated men.” It was a “rural-evangelical virus”, spread around America by “the country Protestant”.

You can picture these people with fine precision: the ideological ancestors of Pat Robertson and every other Christian fundamentalist crank. This viewpoint, however, is a myth. An excellent myth which appeals to our contemporary intuitions about religion and secularism, freedom and authority. But a myth, nevertheless.

The “crusading mind” that characterised the temperance movement was underpinned not by reactionary impulses, but by the principles of social justice. As Mark Lawrence Schrad puts it in his utterly fascinating new book, Smashing the Liquor Machine, “Prohibitionism wasn’t moralising ‘thou shalt nots’, but a progressive shield for marginalised, suffering, and oppressed peoples to defend themselves from further exploitation”.

Consider, for instance, someone like Carrie Nation. Born in Kentucky and raised in Missouri, she became infamous for going into taverns and smashing their windows with a hatchet. She has been described as a Bible-thumping Amazon. Some historians blame her strange behaviour on menopause and sexual frustration. If you search for her name on Google Images, the first picture that comes up shows her holding a hatchet on her gloved right hand and an open Bible on her left. She looks absolutely terrifying; Mary Whitehouse decked in black in Midwest America.

But looks, as they say, can be deceiving. As Schrad puts it: “She was not some Bible-thumping, conservative ‘holy crone on a broomstick’, seeking to legislate morality or ‘discipline’ individual behaviour”. Rather, she was a “populist progressive” who viewed alcoholism as a social evil that, among other things, endangered women.

In Kansas City, she built a women’s shelter. And when she retired, she built an institution called “Hatchet Hall”, which Schrad describes as “part rest home for the impoverished elderly, part safe haven for women fleeing abusive husbands, and part homeschool for their children”.

Crucially, she didn’t view the “drinker as a sinner”, but as a victim, like “prostitutes” or “slaves”. The sinner was the person selling the drink. The same is true of other prohibitionists: they made clear that their objection was not against the person drinking, who they saw as a victim, but the liquor traffic that exploited them. Some people today would say they had a saviour complex.

Nation was also anti-racist. She donated “her lecture proceeds to the black African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. And when she did speak at churches that denied blacks, she demanded that all be admitted entry. If that made racists uncomfortable, well, then they could leave”. Indeed, the relationship between temperance, women’s rights, and black civil rights was a close one. Most abolitionists, suffragists, and civil rights leaders in the nineteenth century supported prohibition.

William Lloyd Garrison, editor of the influential abolitionist newspaper The Liberator, was also a staunch prohibitionist. In a letter he wrote in 1830, he states his principles clearly: that because “all men are born equal, and endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights,” it means:

“That intemperance is a filthy habit and an awful scourge, wholly produced by the moderate, occasional and fashionable use of alcoholic liquors—consequently, that it is sinful to distil, to import, to sell, to drink, or to offer such liquors to our friends or laborers, and that entire abstinence is the duty of every individual.”

Women’s rights leaders like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were also prohibitionists, and formed together the New York State Temperance Society. There they proclaimed it was the duty of women “to speak out against the liquor traffic and all men and institutions that in any way sanction, sustain, or countenance it”. At the women’s rights convention organised by Anthony and Stanton in 1866, Frances Harper, whom Schrad describes as “the most prolific and bestselling black poet and author of the nineteenth century”, spoke. Like “most abolitionist suffragists”, she was also a “proponent of temperance”.

Or consider the more recent example of Walter Rauschenbusch. He was a Baptist minister during the Progressive era — the early decades of twentieth century America — who espoused Social Gospel: a form of Christianity utterly dedicated to fighting against social injustice and exploitation. Rauschenbusch saw the liquor industry as a source of these evils, and was cited by Martin Luther King as a key influence.

So why is he overlooked in accounts of prohibitionism? As Schrad puts it: “Walter Rauschenbusch upsets all of our two-dimensional stereotypes of evangelical Christianity. He was compassionate, not commanding; cosmopolitan, not conservative; socialist, not reactionary”. As a result, “the most influential evangelical of his day almost never appears in traditional prohibition histories”.

Nor was the temperance movement limited to America. To strengthen his point that the movement was progressive, rather than reactionary, Schrad widens his analysis by examining prohibitionism around the world. He points out social democrats like Belgian Emile Vandervelde and Swedish Hjalmar Branting espoused it; Tolstoy and Gandhi, advocates of non-violent resistance and opponents of social injustice, also promoted it.

Even Lenin, perhaps the most consequential Leftist of the twentieth century, subscribed to temperance; he viewed Vodka as a tool used by the authorities to stupify and subjugate the masses. (Lenin was also opposed to free love, which he considered a bourgeois rather than proletarian demand. He thought sex had a “social interest, which gives rise to a duty towards the community”. Shame he was also a mass-murdering tyrant.)

Closer to home, there was also a temperance movement in Britain and Ireland. Henry Vincent, an influential leader of the Chartists, wanted to connect the Chartist movement with the Temperance Society. Meanwhile, nineteenth-century Ireland, under the influence of the Irish priest Thebold Mathew, had a greater proportion of people who followed temperance than anywhere else in the British isles. (Yes, you can read that last sentence again.) As Schrad writes, when mass immigration to the States happened in the wake of the Irish famine, “the Irish Paddy fresh off the boat was statistically more likely to be a teetotaler than the heavy-drinking white, nativist evangelicals in the American heartland”.

Frederick Douglass, the iconic abolitionist leader, was particularly inspired by his friendship with Father Mathew. In a lecture Douglass delivered in Cork, he said: “Seven years ago I was ranked among the beasts and creeping things; to-night I am here held as a man and a brother”. He added: “If I can but forget the position in which I once was, I can turn my attention to teetotalism, and shall be able to speak as a man for a few moments”.

The dignity conferred on him by a teetoller is the same dignity as being a free man — the implication being that slavery and drunkenness are fundamentally akin. Both are ways through which we exploit our fellow man. Douglass emphasised this connection between drunkenness and slavery by stating: “If we could but make the world sober, we would have no slavery”. Two days after his speech, Douglass took Father Mathew’s temperance vow.

So why has our understanding of prohibitionism been so distorted? The main reason, I suspect, is because we project contemporary assumptions to the past. Prohibitionism was reactionary because it was led, in our mind, by evangelical Christians — while forgetting or ignoring the fact that the campaign against the slave trade, for instance, was led by evangelical Christians, or that many influential early feminists, like Josephine Butler, were also evangelical Christians.

Yes, abolitionists and early feminists, like the temperance movement, were irritating busybodies. They did often look a bit scary. But they also proudly espoused views — such as the inherent dignity of black people and women — which may seem common sense to us now, but were certainly not back then.

So, strange as it may sound, when we clink our glasses today, let us spare a thought for the temperance movement. Many of the same people involved in that cause were right on fundamental issues. More to the point: the principles that underpinned those correct views were the same principles that animated their prohibitionism. Surely we can all drink to that.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe