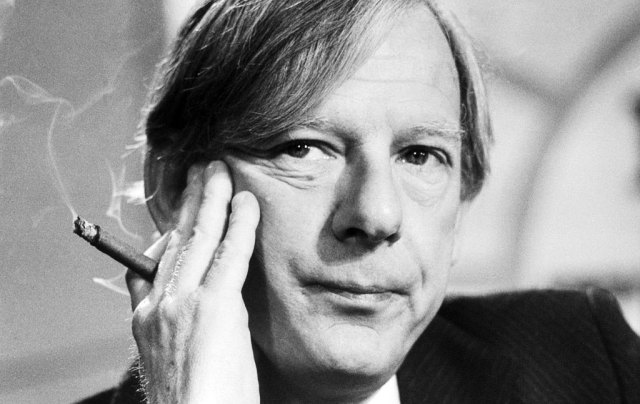

Peter Shore wouldn’t have lost the red wall. Credit: Graham Turner/Keystone/Getty Images

It is one of those speeches that always gives you goosebumps — no matter how many times you hear it. The 1975 Common Market referendum was just two days away and the Oxford Union had brought together some big beasts to debate the motion: “…that this House would say ‘yes’ to Europe”. Edward Heath, Jeremy Thorpe and Barbara Castle all made their pitch. But it is Peter Shore’s contribution that has gone down in the annals of history.

The ‘No’ campaign was obviously heading for defeat. But that didn’t stop Shore arguing with all the passion of someone who believed things to be on a knife-edge. Millions watched live on television as this Labour cabinet minister implored them to resist the prophecies of the doomsayers and have confidence in their ability to manage their own affairs.

“The message that comes out is fear, fear, fear,” he said, gesturing towards Heath, the ardent Europhile. “Fear because you won’t have any food. Fear of unemployment … A constant attrition of our morale … A constant attempt to tell us that what we have — and what we have is not only our own achievements, but what generations of Englishmen have helped us to achieve — is not worth a damn.” Now, asserted Shore, that the fraudulent arguments of the Marketeers were exposed, “What it’s about is basically the confidence and morale of our people. We can shape our future … We are 55 million people … I urge you to say ‘no’ to this motion.”

It is one thing to be a fine platform orator; it’s another to have the intellectual heft to back it up. Shore had both gifts. Born in 1924 to middle-class hoteliers, he spent his early years on the Norfolk coast. When the depression forced the sale of the family business, they relocated to Liverpool, with Shore’s father returning to his previous career in the Merchant Navy. After Cambridge, wartime service in India with the RAF and several years as a Labour Party staffer, Shore was elected in 1964 as the member of parliament for Stepney in East London. Within three years, he was inside the Cabinet.

Peter Shore was the kind of politician you rarely see today: an unashamed interventionist who believed that the proper role of government was to use all the levers at its disposal to manage the economy in the interests of the people. Shore saw government as a force for good and understood that, in its relationship with the market, it must act as master and not servant. This meant regulating markets and not allowing them to let rip. It meant speaking the language of competitiveness, exchange rates and industrial strategies. It meant, ultimately, the elevation of the needs of the real economy — where goods were produced and wealth created — over those of finance capitalism; the prioritisation of full employment, growth and living standards over monetary targets as macroeconomic policy goals.

It was this driving philosophy which ensured, during the IMF crisis of 1976, that Shore was not seduced by the arguments of Prime Minister Jim Callaghan or Chancellor Denis Healey — they, along with others in the Cabinet, suggested that if Britain couldn’t spend her way out of recession, she had no choice but to embrace the precepts of Friedman-style monetarism. And it was Shore’s deep-seated belief in the capacity of the state to improve people’s lives — and the duty of democratically-elected politicians to drive such improvements — that informed his opposition to Euro-federalism. Like many who stood in that rich tradition of Left-wing Euroscepticism, Shore’s antipathy was not to Europe, the continent; he simply objected to an arrangement that served the interests of bankers and the multinationals over ordinary working people.

He thought it wrong to give primacy to the views of technocrats over those of elected representatives. Shore saw the objectives of those driving political and economic integration across Europe as antithetical to not only the aims of the British labour movement but the concept of democracy itself.

Oh, to have had Shore and other big beasts of the Eurosceptic labour movement — Michael Foot, Tony Benn, Hugh Gaitskell, Bob Crow and Barbara Castle — around in 2016, to articulate the entirely rational Left-wing case against the EU, and to act as an antidote to the cynicism and hysteria that infected so much of the Left during that period.

Peter Shore stood for the Labour leadership twice: in 1980 and 1983. What might have been if he’d won, and then become Prime Minister? Labour would not have retreated from its historical economic radicalism. By the early 1990s — just as it had done for the second part of the 1970s — the party had come to broadly accept the argument that “There is no alternative” to market fundamentalism, and that elected governments must be no more than minor actors in the operation of the economy. A Labour Party — and country — led by Peter Shore would not have succumbed to such pessimism. Nor, most likely, would the party have developed the infatuation with the EU which has done so much to alienate millions of its once-loyal supporters over recent years.

The driving philosophy of this government would have been that democratic socialism was possible only if politicians of the Left were willing to step up to the plate and take control of the nation’s economic destiny rather than hive off responsibility to markets and technocrats.

As a Labour PM, Shore would have led from the front in opposing the Single European Act and Maastricht Treaty. Britain would not have entered the Exchange Rate Mechanism, and the ignominy of Black Wednesday would have been avoided. Shore would have resisted, too, the drive towards the internationalisation of capital which has facilitated a global market where power and wealth are concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, and multinationals have the whip hand over elected governments.

He would not have hesitated to prioritise the interests of the productive sector over the City. His Keynesian interventionism and his focus on competitiveness would have ensured Britain did not experience the decimation of her manufacturing base that came to pass under Margaret Thatcher and her successors. Hundreds of thousands of blue-collar jobs would not have been lost to overseas competitors.

Shore — like so many Labour heavyweights from yesteryear — was a patriot to his fingertips. A Labour Party shaped in his image and following his credo would not have lost touch with working-class communities, a drift that began three decades ago, around the time Shore stepped down from the front bench. And our nation as a whole would have been much the better for it.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe