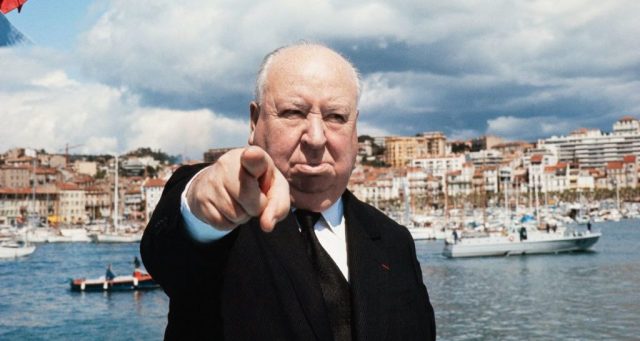

Hitchcock in Cannes (Photo by RALPH GATTI/AFP via Getty Images)

There was only one woman in Alfred Hitchcock’s life. She wasn’t his wife. She was a type. Elegantly-dressed, blonde, with an inscrutable surface concealing a subterranean sexuality. And he treated the stars who played these roles like mannequins. Ingrid Bergman fit the mould; but then she ran off with Roberto Rossellini. His favourite was perhaps Grace Kelly. But she ended up marrying a prince. In 1961, when his wife Alma pointed him to a drinks ad on TV, Hitchcock had a coup de foudre: he had found another blonde.

Tippi Hedren had never acted before. But on the basis of that advert alone Hitchcock offered her a five-year contract on $500 a week. He first cast her in The Birds, his dreamscape horror film set in northern California. The fact she wasn’t a star meant Hitchcock had greater leeway to exercise his Pygmalion instincts: he instructed her on what to wear, what to eat, what friends to see, and he isolated her from the other actors. Hedren later accused Hitchcock of sexually harassing her in Marnie, their final film together.

How did a greengrocer’s son from the East End of London, end up, by the time Marnie was being shot, the most powerful film director in the world? Edward White’s enjoyable jaunt through the different aspects of Alfred Hitchcock is not a straightforward biography; we don’t go from baby Hitch at the twilight of Victorian England to a portly octogenarian in sunlit California. The Twelve Lives of Alfred Hitchcock examines Hitchcock thematically. Through these themes an answer to that question emerges.

Hitchcock grew up in Edwardian London. As a boy, he read Edgar Allen Poe, John Buchan, and G.K Chesterton — works of fiction that combined cheap thrills with weightier metaphysical themes of dread and alienation. He loved the West End, and grew up in the culture of music halls and pubs. Both parents had Irish backgrounds, but his father was raised in the Church of England. When his father married his mother, he converted to Roman Catholicism.

He retained in later life all the fears and anxieties of his childhood. He was scared of policemen, strangers, driving, solitude, crowds, heights, water, and conflict of any sort. Like a child playing with his favourite toys, he preferred to work on sets rather than locations. And it is childishness, this desire for control, that, paradoxically, fuelled his status as an auteur.

Hitchcock was christened as such by La Nouvelle Vague, that avant-garde movement from the country that invented the cinema. But he was never the sole “author” of his films. Unlike Woody Allen or Quentin Tarantino, “when it came to screenwriting, Hitchcock relied on the talents of others”. Nevertheless, all his scripts had to have a “Hitchcock touch”: “The biggest trouble”, he once said, “is to educate writers to work along my lines”. He also had to educate actors to work along his lines, and this dictatorial approach to female actors, especially, is the most troubling aspect of his career.

White describes Hitchock’s relationship to women as “complex” and “contradictory”. On the one hand, “he surrounded himself with women, sought out their friendship, gave them responsibilities and opportunities that few men of his station did, and proudly championed their work”. But on the other hand, it was through women that “he revealed the darkest, most discomfiting parts of himself”. White wonderfully describes him as a “curious brew of J. Alfred Prufrock and Benny Hill: English repression meeting English bawdiness, which may be two sides of the same coin”.

Hitchcock claimed his life with his wife Alma was celibate, and joked that when they conceived their only child he used a fountain-pen. When directing his first film at 25, The Pleasure Garden, he was baffled when one of the actresses refused to go inside water for a drowning scene. A cameraman had to explain to him what menstruation was: “I’ve never heard of it in my life!”. Yet a few years later, during a screen test with the Czech actress Anny Ondra for his first talkie film Blackmail, he questioned her on her sex life.

He also maintained throughout his career that he made films “to please women rather than men” because the majority of cinema-goers were supposedly women. White points out that the producer of his TV show was a woman, as were many of the screenwriters he worked with. Still, the most famous scene he ever shot features a woman, who the audience had up until then thought was the protagonist of the story, being stabbed to death less than halfway through the film.

Psycho cost $800,000 to make, and it made 15 million dollars. Hitchcock self-financed the film, and its success made him the richest director in America. After the high-budget Technicolor suspense thrillers of the 1950s with Grace Kelly, James Stewart, and Cary Grant, Psycho was a different affair. It was a black-and-white horror. The famous shower scene, lasting 50 seconds, took seven days to shoot. Chocolate syrup was used for the blood, and Janet Leigh’s body double for the scene was the Playboy model Marli Renfro.

The most remarkable thing about the film was not the content, though, but the publicity. Hitchcock made cinema managers sign contracts which forbade audience members from entering the film after it started. He also ordered that, after the final haunting shot of the film was shown, cinema lights be kept low for a further thirty seconds. The effect was electric. Audience members apparently ran out of their seats; many soiled themselves. Promotional posters for the film featured Hitchcock pointing to his wristwatch next to the words: “No one … BUT NO ONE … will be admitted to the theatre after the start of each performance of ALFRED HITCHCOCK’S PYSCHO”. He was a consummate showman.

This concern for appearance was also evident in his attire. White dedicates one chapter in his book to exploring Hitchcock as a dandy. “Despite looking like a staid British bank manager”, White writes, “Hitchcock apportioned great depth to the surface of things. He wasn’t showy”, but “he was committed to the perfection of appearance as a way of exerting control over himself and the world around him”.

After he became rich in the mid-twenties, Hitchcock made a pilgrimage to Savile Row to establish his look: “dark business suit with white shirt, dark tie, and highly polished black shoes”. This trademark look was more than a disguise: it was, as White quotes Philip Mann on dandies, “a uniform for living”. The clothes expressed his soul. And that an outward appearance can express a soul illustrates an equally important element of Hitchcock’s aesthetic vision: Catholicism.

“One should add”, White writes, “that English cultural life in the years of Hitchcock’s childhood and young adulthood was more informed by Catholicism than at any moment since the early seventeenth century”. The two most prominent dandies in the decade Hitchcock was born, Aubrey Beardsley and Oscar Wilde, were converts to Catholicism. Two novelists born less than a decade after Hitchcock, Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene, would convert later. Chesterton was a favourite of Hitchcock’s childhood. According to White, “the identifiably Catholic idea that can be found in Hitchcock’s aesthetic sensibility” is that “surface beauty is transcendental, a gateway to another dimension of experience”. He adds that “some of the most famous shots in Hitchcock’s films display objects that seem to be imbued with forces, good and evil, beyond the physical realm”.

There’s a tension, according to White, between Hitchcock’s Catholicism and his experimental techniques: “the magical elements of Catholic teaching to which Hitchcock was drawn were defended fiercely by the Vatican in the years of Hitchcock’s creative life as a bulwark against modernity — a condition that Hitchcock not only grasped but embodied”. Nevertheless, White contends Hitchcock found a way to fuse the “magical” and the “modern”: “he had a fixation with technique and precision planning, but this was used to create a filmic world that slipped the grasp of science, technology, and rational thought”. He used modernist techniques, then, but resisted the overarching beliefs that explained them. And the Catholicism that suffused his films was the vague and cryptic kind, not clearly articulated doctrine.

This is why, perhaps, when people asked Hitchcock what his films were about, he shrugged: “I don’t give a damn what the film is about”. He disdained attempts to find larger meanings in his work; he wanted them to be appreciated for their form and visual excellence. In this sense, he resembled the novelist Vladimir Nabokov, who claimed of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina: “Any ass can assimilate the main points of Tolstoy’s attitude toward adultery but in order to enjoy Tolstoy’s art the good reader must wish to visualize, for instance, the arrangement of a railway carriage on the Moscow-Petersburg night train as it was a hundred years ago”.

Both rejected ideological or moralistic readings of their work; both were characterised by their stylistic virtuosity; both were fascinated by obsessional love and delusion; and both exercised omnipotent control over their art. Hitchcock’s control over his actresses recalls Nabokov’s description of his characters as “galley slaves”. Hitchcock and Nabokov were both born in 1899 and took America as their home at around the same time: they were two expats from the Old World who gave sunny post-war America a sinister edge.

In November 1964, Hitchcock had even written a letter to Nabokov asking him to write a script for two films. The first was a spy film, which Nabokov declined. The second was about “a teenage girl who realises that the hotel run by her family is a front for an organised-crime operation”. Nabokov was intrigued by this, but it never came to fruition: “Demands on both men’s time meant the collaboration never happened”. Our loss.

Nevertheless, even if his films were not about large overarching themes, White’s book shows they were nevertheless a crucible through which many of the currents of the twentieth-century clashed. Hitchcock wanted us to watch his films for entertainment; but we know they are more than that. He was a modernist and a Catholic. Elegance and charm mixed in his films with sex and violence. As White notes near the end of this stimulating book, Hitchcock’s “variegated legacies, buttressed by his phenomenal talent and unconventional personality, make him a codex of his times, usually complex, often troubling, but always vital”.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe