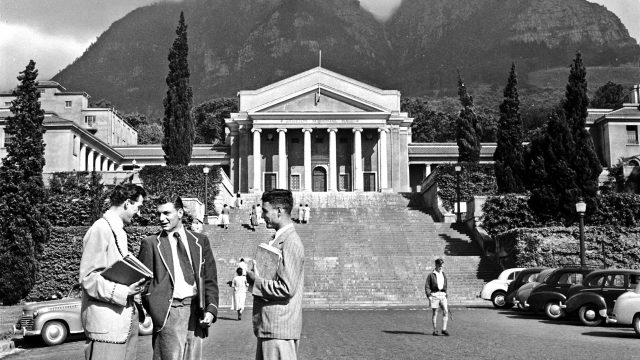

If Sebastian Flyte had been in South Africa. Credit: Evans/Three Lions/Getty Images

On a clear day, from my school playing fields, I could see the university that I would one day attend. It was the University of Cape Town, a Doric crow’s nest, perched high on the side of the Table Mountain chain.

My young life was a travellator up that mountain. I come from precisely that generation for whom attending university was a no-brainer for those in the brains game. And I come from a place in which where you would go to university wasn’t something you ever had to think about. There were only two full universities within a 400-mile radius — and one of those taught in Afrikaans.

The tyranny of choice, the terror of UCAS, the holy mysteries of “clearing”, all passed me by. As did the English “university experience”. When your university is a twenty-minute drive from your family home, you live in that family home. The upside of this model is that you can enter adulthood without much debt. The downside is that university becomes a kind of superannuated school experience: all the same friendship cliques re-establishing themselves. It can easily become a flatpack, wipe-clean lifestyle, notably low in personality formation, windswept romance and regrettable fumbling. Home by half past three. Dinner on the table at half seven. A time of bland stasis, at exactly the moment when everything from Brideshead Revisited to The Young Ones has promised you a rite of passage, adulthood and “freedom”.

These days, having lived in the country for over a decade, I can bluff Englishness easily: I’m odourless, flavourless, practically indistinguishable. But when it comes to that military service for the middle classes, The University Experience — that particular confection of shoe-vomiting on cobbled stones, of WKD-saturated student unions, of “blowing your grant on pills and Beefa then subsisting on baked beans for two months”, all the clichés — I know it only through careful study of BBC3 sitcoms and mid-period Adrian Mole.

Back then, this rankled — so much that one year into a degree, I dropped out, hopped a plane to England and spent 15 months emptying drip trays in a series of bad pubs and worse hotels, in search of a life less ordinary. Up above the bars, in scabby live-in rooms, I scanned various kinds of .gov.uk bumpf, searching for a way to join the English University Experience, until I managed to piece together that it would cost £12,000 per year excluding accommodation, no loans available. I binned the dream, and eventually returned home, thereby performing the uncommon feat of dropping-back-in.

This was still the Mbeki era, when the nation’s farcical political successes of the 90s hadn’t quite dimmed, and a sense of collective purpose still spanned from black to white. In South Africa, the key problem of student politics was “student apathy” — the student paper would run endless pointless pieces on it. A few years later, the storm clouds of Rhodes Must Fall would herald a prickly new world, but at that moment, university was positively prelapsarian. Identity politics was already inside the seminar rooms, but not yet beyond them. Cancellation was unheard of. One winter, a charity I was involved with staged a Big Brother-style live-in contest in a fake squatter camp on the main plaza. Coceka, the girl who won, did so with the slogan: “Keep the black in the shack”.

The university experience, such as it was, was a reflection of the city from which it emerged: suburban, laid-back, jocky, mildly anti-intellectual. The campus was dominated by the Commerce faculty — the eccentric if admirable British insistence on studying impractical subjects, like Spanish, Classics, or History, being largely absent. In a country with no social safety net and stonking unemployment, the wonderfully genteel mentality that leads to so many Brits spending three years studying History of Art is either for the high bourgeoisie or the terminally insane. The system of post-undergrad conversion courses and the graduate fast-tracks is a rather backwards-engineered First World bauble.

In recent years, my position has come full circle. Ever more, I feel sorry for the English. I feel sorry for the rampant grade inflation in their school system, such that every fresh year requires another wheelbarrow full of A*s to buy a simple 2:1 from Leicester de Montfort. I feel sorry for the firewall of clichés that bound their experience. Most of all, I feel sorry for the oppressively hierarchical nature of the system — the tyranny of the eternal CV distinction between Imperial and King’s, between Bristol and Durham, Nottingham and Nottingham Trent.

And that hierarchy maps onto the job market, too, when you finally get into it. I recently worked with someone who beat out 5000 applicants to a BBC traineeship. The list of fillips you need on your CV to do that these days is mind-boggling. When people talk of “late stage capitalism”, this may be what they mean: a level of competition that turns the humans underneath it into mere abstractions of tendencies.

On the rare occasions employers have been made to scan my resumé, the Higher Education section has likely only baffled and annoyed them. Where exactly does this guy stand in the great horse race of British society — is he more Manchester or is he, you know, a bit Bournemouth?

The truth is that UCT was both and neither: South Africa is simply not the scale of higher education universe that can sustain twenty different words for “upper management material”. At the school on the hill, you got some world class profs, but you also got proper dimbos. It’s neither clubbable nomenklatura nor cultural wasteland. Some of the people I met went on to real greatness. From time to time, I look up the student paper’s chief sub, now a professor at Cornell publishing things like: “Quantum-dot spin-photon entanglement via frequency downconversion to telecom wavelength”. But then you also got the same loping C students who’d been along for the ride since high school. Throw into that the kids from township schools, who slogged through remedial years on lower grades, and you’ve got a fairly balanced pool of talents, all centred around the geography of the city itself. It made for a world that felt human in scale.

By contrast, the rigidly stratified British model seems to involve taking every BBB in the country, and disinterring them to one market town in the Midlands. On this lunar landscape, the colonists will never meet anyone from outside of their IQ standard-deviation. Even the Left-wing interest in social mixing ends at the eleven-plus. A very smart friend completely mucked up his A Levels, and ended up at a lower-tier university. He describes being treated as vaguely godlike by his peers and tutors in the seminar rooms: The Guy Who Seemed To Know What Derrida Was On About. It was perhaps awkward for each party to become aware of that gulf — and of quite what it was each wasn’t getting.

But whatever they lacked, they were getting their latter-day equivalent of the Grand Tour. In the era of Massive Open Online Courses, the price of knowledge is fast approaching zero. And the price of credentialism — of having the piece of paper that pushes you through the recruiter’s door — is finally in recession, as employers get wise to years of academic hyperinflation. In a society that has mislaid many of its rituals, one consumerised Rite Of Passage seems more popular than ever. The eternal desire of kids is to escape their parental homes and go ape — the Cameron reforms simply succeeded in opening the system up to working class kids also eyeing up the same domestic tourism bargain as the middle classes. But post-Covid, it does seem that the long-awaited reckoning on the value of higher education might be about to take place. It is no longer a no brainer.

I was desperate to get out of the provincialism of the New World. But as I look back, I doubt that swimming among Oxbridge super-achievers would have given me nearly as much imaginative scope. Hothousing can be the whetstone to greatness, but it’s also a good recipe for over-narrow specialisation. When I dropped back in, I realised that everything I wanted had been there all along, if I just threw myself into it. Competition for places on the student paper was thin. You could muck about, write what you liked, build fiefdoms, get weird. I did, and it was the making of me.

Perhaps, far from the Oxbridges of the world, the platonic ideal of a university was always much closer than I’d imagined. 9-5, in the Colonies. If you’re going to dream on a spire, you want to have a sense that you’re Sebastian Flyte lounging on a lawn, not hyper-ventilating in a library.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe