A child receives a coronavirus vaccination in Utrecht, Netherlands. (Photo by Patrick van Katwijk/BSR Agency/Getty Images)

There is an irony, which is that on so-called Freedom Day, it was announced that one freedom would not be expanded. Nadhim Zahawi, the vaccine minister, declared yesterday that only extremely vulnerable children between the ages of 12 and 15 would be offered the vaccine: that is, children who have severe disabilities or who are immunocompromised.

The Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) explained that this is the result of a risk-benefit analysis. The JCVI’s Prof Adam Finn in a briefing with the Science Media Centre pointed out that “happily the virus very rarely affects children seriously”, and that the very small risks of adverse effects from the vaccine outweigh the risk to a child of getting, and then becoming ill with, Covid. The UK medicines regulator has declared the Pfizer vaccine safe and effective in children, but the JCVI has a more stringent approach.

Similar calculations were made back in March. At the time, a small number of cases of a rare clotting disease were detected in people who had had the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine. As a result, the JCVI recommended that it not be used in the under-40s unless no other options were available.

That decision was based on a straightforward risk-benefit analysis. The risk of a blood clot caused by the vaccine is vanishingly small – about one in 50,000, with the risk of severe health impacts lower still. But young people are also at very low risk of getting severely ill if they develop Covid, and the number of people with Covid at the time was very low – only about 6,000 new cases a day, compared to about 60,000 at the January peak. That meant that the chance of a young person getting infected, and then getting very ill, was even smaller than the risk of a blood clot, as the Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication showed.

“Freedom Day” has happened now. It’s far from clear what effect it will actually have. The Government’s Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Modelling (SPI-M-O)’s latest modelling paper, published last week, says that by the end of August, we could end up with fewer than 100 hospitalisations a day, or more than 10,000.

Small changes to our assumptions drive huge changes to the outcomes: will 90% of people stop wearing masks? 70% 50%? Will we all pile into nightclubs and theatres, or only a few of us? We don’t know: these things, or a million others. As the Bristol maths professor Oliver Johnson puts it, “the range of uncertainty around any reasonable forecast probably includes both ‘it’s basically fine’ and ‘we have a very serious problem’.”

What we do know, though, is that cases were already growing before Freedom Day. The R value is well above one. If we wanted to reduce the number of cases, to make the line on that chart actually go down, then we would need to reintroduce some (probably quite stringent) measures. That seems unlikely.

But what we can do is get more people vaccinated. And it seems that two obvious ways of doing that are to vaccinate children, and to start using the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine in younger people again.

Vaccination makes a huge difference to Covid risk, in every way. Which is why it’s a problem that our programme has tailed off so much. On one glorious day back in March, 844,000 vaccine doses were reported to have been administered across the UK. That was anomalous; but from March until about June, there was an average of between 500,000 and 600,000 doses being administered every day.

Since early June, though, those numbers have sagged dispiritingly. It’s been more like 250,000 for the last few weeks.

So how do we get it back up to higher levels, given that vaccine coverage is more important than ever?

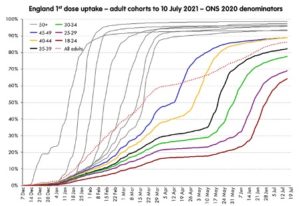

There are two drivers of vaccine uptake: supply and demand. The most obvious problem, at the moment, is that demand is down. Paul Mainwood, a strategist who has spent recent months looking at vaccine delivery, points out that first-dose vaccine uptake shows a distinct curve. At first, each age group is vaccinated slowly, so the numbers creep up; then it accelerates, and shoots upward; then, as it nears 100%, it levels off again. The curve on the graph is S-shaped..

With the over-50 age groups, that flattening-off happened at above 95% coverage; but as you come down the cohorts, the levelling-off happens earlier and earlier. For 30- to 34-year-olds, the line has flattened significantly and it hasn’t yet reached 80%. For 18- to 24-year-olds, it’s lower still: the flattening is visible and it’s only around 65%.

That suggests that there is reluctance among younger people to get the vaccine. Whether that’s true anti-vaxx attitudes, or an understandable wariness of feeling rubbish for a day or two in exchange for a reduction in an already tiny risk of death – or an equally understandable, if in my view wrongheaded, concern about the more severe side-effects – is hard to know, although the ONS says that “vaccine hesitancy” is rare. Even among 16- to 29-year-olds, the most hesitant group, only 13% say they are reluctant to take the vaccine. But even if they’re not reluctant, we seem to be running out of people who are noticeably keen.

How you persuade those increasingly hard-to-reach groups is disputed. Finn of the JCVI said that one reason they were being so stringent is that they are worried about “the impact on public trust” if the JCVI recommends vaccines for groups who would not directly benefit from them: I worry about the opposite problem, about the impact on public trust if you tell the public that the vaccines aren’t safe.

But given that demand is a problem, it does seem that an obvious way to increase demand would be to widen the availability of the vaccine. About 20% of the UK’s population is under 18; roughly 13 million people. Probably about four million of those are between 12 and 18. We can expand demand simply enough by offering it to them.

One question is, of course, whether we could vaccinate those young people quickly enough to make a difference.

It does seem that the UK is not, right now, struggling with supply. I spoke to Kevin McConway, emeritus professor of statistics at the Open University, and he noted that all his local vaccine centres have walk-in availability for Pfizer, suggesting that it’s not an immediate problem.

But Mainwood estimates that we are bumping right up against our supply with Pfizer. If we were to take steps to speed up vaccination – by offering second doses earlier than eight weeks, for instance, or by allowing teenagers to be vaccinated – we would struggle.

The thing is, though, we have literally millions of AstraZeneca vaccines sitting unused. We bought 100 million. It’s very hard to get detailed breakdowns of which vaccines have been used, something that Professor Sir David Spiegelhalter, who I spoke to, is somewhat annoyed by: but we can’t have used more than 82 million AZ doses, since that’s the total number of vaccine doses administered. Probably it’s more like half that.

And since those March days when the AZ risk-benefit calculations were carried out, the situation has changed enormously. Now, the number of cases every day is back up around 50,000, not far off the January peak. The latest ONS infection survey finds that around one person in every 95 has the disease right now. And it’s highest among the youngest age groups – almost 3% of 17- to 24-year-olds have it. The Winton Centre’s analysis suggests that when the numbers are that high, the risk-benefit analysis changes utterly. A twentysomething has about a one in 50,000 chance of a blood clot if they get the AZ vaccine ,but a higher than one in 16,000 chance of going into intensive care with Covid in the next 16 weeks if they don’t.

If we freed up those AZ doses, we could do all sorts of things. For one thing, we could offer people a mix-and-match vaccine dose, so that people who want their booster earlier than eight weeks could do so. The evidence of effectiveness for mixed Covid jabs is now quite good, and it may even be more effective than two jabs of the same dose.

And we could offer vaccines to older teenagers who are willing, with their parents’ consent, to take a very low risk of vaccine side-effects in exchange for a significantly decreased risk of spreading the disease.

People should be able to make these decisions, or in the case of older children, to make them in concert with their parents, just as we allow them to make other decisions about risk and wellness. Perhaps they would need to sign a waiver; but they should be allowed to.

In about seven weeks, children will be going back to school after their summer holidays. The virus will, in all likelihood, still be circulating at least as much as it is now. We will head into winter with few restrictions, possibly with new variants, and still, probably, with a large percentage of the population unvaccinated. We could significantly reduce that percentage if we allow people to make their own decisions about what is important.

Now that Freedom Day is here, we ought to allow people a real freedom: the freedom to choose to be vaccinated.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe