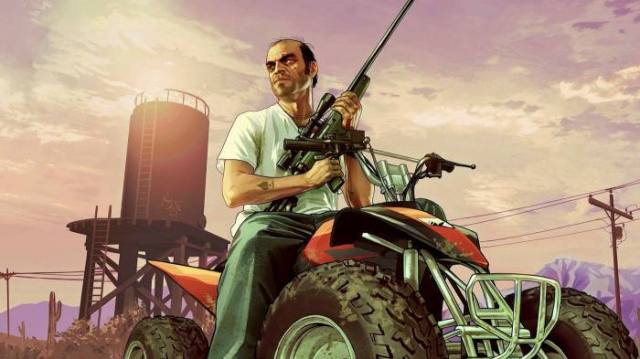

It’s actually quite fun (GTA V)

After two gunmen opened fire at a stream of passing cars on a Tennessee highway in 2003, killing one person and badly wounding another, it didn’t take long for the police to find the culprits. Lurking in the bushes nearby were two teenage stepbrothers, who quickly confessed to the crime. But it wasn’t their fault, they explained. They hadn’t meant to hurt anyone. They were simply copying their favourite videogame: Grand Theft Auto III.

Once they were put trial, this claim was taken at face-value by the victim’s family’s lawyers, who launched a $246 million lawsuit against the game’s developers, Sony Computer Entertainment America and Rockstar Games. The case, however, was eventually dismissed. Exactly twenty years after GTA III was released, the debate over violent video games can seem like yesterday’s controversy.

But it’s a theme that keeps reappearing: it was referenced last week by Ted Sarandos, the Co-CEO of Netflix, after criticism of the new Dave Chappelle comedy special. Netflix as a company, Sarandos wrote in an email to staff last week, “ha[s] a strong belief that content on screen doesn’t directly translate to real-world harm”. He continued:

“The strongest evidence to support this is that violence on screens has grown hugely over the last thirty years, especially with [first-person] shooter games, and yet violent crime has fallen significantly in many countries. Adults can watch violence, assault and abuse — or enjoy shocking stand-up comedy — without it causing them to harm others”.

Sarandos has now distanced himself from his remarks, saying they should’ve been made with “a lot more humanity”. But was he right right that videogame violence was a useful analogy? Is it really the case that there’s no translation from virtual to real-world violence? What have we learned in the 20 years since GTA III?

The evidence is certainly confusing. The American Psychological Association published a review of videogame violence in 2015 (updated a little in 2019), which concluded that playing violent videogames does indeed make children, adolescents and young adults more aggressive. But the APA also concluded that there simply wasn’t enough evidence to say whether this translated to real-world criminal violence or delinquency.

In 2020, another set of researchers added an extra dose of ambiguity: they pointed to a number of holes in the APA’s analysis, uncovered lots of studies that had been missed, and noticed on a closer look that many of the studies cited had been very poor-quality. They concluded that the APA had “greatly overestimated” the consistency of the evidence linking videogames to aggression. Although stated with quite some uncertainty, the association between videogames and aggressive behaviour in their new analysis appeared “negligible”. Higher-quality studies since then tend to support that case.

Even worse for the case against videogames, some of the studies that were often cited as evidence for their effects on aggression and violence have come under intense suspicion in recent years. For example, one study that had claimed to show how first-person shooter games “influenced people to aim for the head” when shooting a real gun was retracted after data irregularities were discovered. Several other articles on this topic by one particular academic — Qian Zhang, of Southwest University in China — have also either been retracted or seriously questioned after an investigation by the data sleuth Joe Hilgard.

Not only that, but at least some evidence points in the opposite direction: a number of studies even claim that, after the release of a very popular videogame, crime actually goes down, presumably due to the potential perpetrators — and their victims — being incapacitated, or perhaps self-incapacitated, by the game. That is, people are safely staying inside, committing virtual slayings and virtual bank robberies instead of getting mixed up in real-world crime. One such study specifically pointed to the most recent Grand Theft Auto instalment, 2013’s GTA V, as having these crime-dampening effects.

Such evidence — showing that violent video games actually reduce real-world violence, rather than just being unrelated to it — seem almost too good to be true, if you’re on the pro-videogames side of the debate. Of course, the data they use is just an overview: we can’t be sure that the specific people who avoided crime did so because they were staying at home playing GTA; we don’t have individual-level data and they might have been doing something else entirely. But a few studies have now found similar results, and the self-incapacitation effect does seem intuitively plausible — perhaps more plausible than the idea that after an intense session of GTA, players would feel the urge to put down the controller and go to seek out a real-life scrap.

The results seem particularly convincing for games from the Grand Theft Auto series, simply because they’re so astonishingly popular. GTA V alone has sold more than 150 million copies — and with a game that’s by all accounts extremely absorbing and addictive, that’s a lot of potential people off the streets. To return to the point made by Netflix’s Ted Sarandos, the immense and increasing popularity of such violent games while crime rates have either dropped or flattened out should at least give pause to anyone who wants to draw a causal link between the two. After all, an awful lot of people are playing these games, however much non-gamers might find the whole thing baffling.

And that’s perhaps the distinction we should draw: between the quality of a piece of art or media, and its effects. These aren’t the same thing: our sense of disgust or moral disapproval doesn’t necessarily pinpoint the things that are really toxic in our environment. Bad quality and bad effects surely overlap sometimes, but it’s too common to see them conflated — to see a “this is in bad taste” argument masquerading as a “this has bad effects” argument.

In fact, what we might need is to rehabilitate the act of criticism, or even the idea of aesthetics itself. Thoughtful criticism of our cultural objects — including videogames — is a good thing in itself, and needn’t rely on whether they have good or bad effects in the real world. The full picture of what makes something beautiful, or what gives it artistic value, can of course include its real-world consequences (if any). But those are among the most difficult things to pin down. Critics shouldn’t play at being scientists when their aesthetic criticism is valuable regardless.

Likewise, scientists should avoid playing at being critics, and not let their sense of aesthetic distaste or moral offence interfere with the sober, disinterested gathering of data that solid research requires. It’s surely not going too far to argue that a sense of distaste about videogames was what led the scientists mentioned above to overlook the bad — perhaps fraudulent — studies that pointed to their bad effects.

Is Grand Theft Auto III a good piece of art? Not really. It did represent a watershed moment in game design — the subsequent 20 years have been stuffed full of games that built on, or ripped off, its general setup. And whereas it did allow players to wander around a city with a sniper rifle blowing the heads off randomly-chosen pedestrians, it also had a relatively sophisticated gangster-movie-like plotline, with a wickedly ironic and satirical view on society — something which many critics (and, to be fair, players) missed. But it wasn’t much of a step forward for videogames in the “artistic value” stakes (for that, take a look at Wikipedia’s list of “games considered artistic”, on which the later GTA V, with its wider cinematic scope, does appear).

Did Grand Theft Auto III cause real-world violence? The evidence would suggest otherwise. The sheer complexity of arriving at an answer to that question, though, should make us substantially more cautious about advancing our pet theory of how this or that medium has massive impacts on our psychology.

Videogame researchers have recently begun to highlight the sheer uncertainty of many of the effects in their field. Perhaps believers in the effects of other media — whether newspapers, books, movies, Instagram or even Netflix comedy specials — should show the same kind of intellectual humility.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe