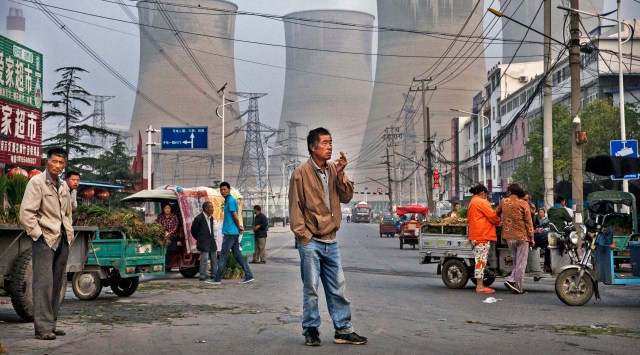

What do the CCP and the Green Party have in common? (Kevin Frayer/Getty Images)

As my plane approached Beijing, it descended into what looked like a layer of cloud. Within seconds, however, it became clear that this was something entirely different: we had just entered the capital’s thick, ubiquitous smog. It was 2012, and Beijing was cloaked in it. The following day, it grew even worse. From my hotel, it was impossible to see the other skyscrapers across the street; normally, the view extends as far as the Fragrant Hills at the outskirts of the city.

Since then, things have improved. But smogs are still a feature of everyday life, serving as a potent reminder of the toll that four decades of rapid industrialisation have taken on the Chinese environment. This is far from a modern problem. Historian Mark Elvin, in The Retreat of the Elephants, plots an almost continuous process of environmental instability in the People’s Republic of China. He traces today’s crisis back almost 2,000 years: to deforestation during the Han dynasty, which accounts for the lack of trees in large parts of central China today.

Certainly my own experience of how this looks in China extends beyond 2012. Seventeen years earlier, while living in Hohhot, inner Mongolia, I remember smogs every bit as dramatic, caused by the high use of coal and fossil fuels. A few years later, one April in Beijing, the skies grew dark in the middle of the day; a severe sandstorm had arrived, and people were forced to flee indoors. Desertification, over-building, lack of water, poor soil quality, destruction of species, appalling air quality — all have been the cause of deep concern to the Chinese Communist Party for decades.

Faced with this weight of evidence, it would be strange if the Chinese government adopted the kind of sceptical attitude that, for instance, some Australian leaders have about any links between human activity and climate. Indeed, much has been written in recent weeks about President Xi’s expected absence from COP26 next week, but it would be reductive to take that as a sign of climate change apathy. China, after all, is situated in a region that has been historically affected by earthquakes, floods and other natural disasters. And in recent decades, let alone months, these have grown more severe.

But China’s politicians find themselves in a quandary: how should they balance these concerns with the country’s imperative to grow at whatever cost, just as the West did during the high phase of industrialisation? Most Chinese citizens seem, even today, to know about the smogs that blighted London in the late Forties and early Fifties. The tactic seemed to be that this sort of occurrence was inevitable, and could be cleaned up once industrialisation had been achieved.

That’s partly why, at the Copenhagen climate summit in 2009, the Chinese delegation, along with 76 other developing countries, largely insisted that the greatest number of carbon emission cuts needed to come from the US and Europe. Most of these places had outsourced much of their most polluting industries to China; per capita emissions comparing an American with a Chinese made the latter pale into insignificance. Looming over all of this was a suspicion among some in China that the whole climate change negotiation was just another attempt by Washington and its allies to put a break on Beijing’s economic development.

By 2015, and the next major conference in Paris, things had changed. Smogs such as those in Beijing in 2012, along with a rising sense of frustration and concern among Chinese citizens, meant a more proactive stance had become necessary. But the most important development had been the appointment in late 2012 of a new national leader, Xi Jinping.

Xi’s politics were focused on appealing to the new middle class — those who lived in cities, worked in services, and were concerned about the cost of living and their quality of life. For them, water, food security and clean air that didn’t kill them were priorities. Yet Xi was by no means an environmentalist for convenience’s sake; earlier in his career, as party leader of the huge, eastern coastal province of Zhejiang, he had been unusual in often talking about the importance of care for the environment.

And so, “Greening” China has become a major policy preoccupation, with Xi’s announcements becoming increasingly bold. After supporting, and then signing up to, the commitments to cut emissions made in Paris in 2015, China’s stance was enhanced by the withdrawal from the deal of America under Trump in 2017. Biden may have later rejoined the Paris agreement, but the damage to America’s image had already been done: Xi was able to claim he was doing more to save the environment than the US. Indeed, this is one of the few issues where China has managed to improve its reputation in the last few years.

A series of pledges to be carbon neutral by 2060, and to aim for peak emissions by 2030, culminated in Xi’s surprise announcement at the UN General Assembly last month that China would no longer build coal-fired power stations abroad. Despite all their perpetual arguments in other areas, in this one, Europe, China and the US at least have some common ground.

Yet paradoxically, China still needs to grow and remains fundamentally reliant on fossil fuels, which constitute the source of two thirds of its energy. The aim to focus on quality of growth rather than quantity is clearly stated by the Xi government. But just how far they can go in squeezing people’s material development by demanding higher costs for energy, and use of more expensive alternatives, is another question. On top of this, it remains unclear whether the targets referred to above — particularly having emissions peak in 2030 — will be sufficient, let alone achievable.

That isn’t to say there aren’t any positives. However critical we might be of the Chinese government, and the political system it operates under, and however sceptical we might be about its real commitment to combat climate, it is surely better that we start from the position we are currently in: one of broad alignment. China led by climate change deniers would be a disaster.

And even if it is self-interest that motivates Beijing, it is also reassuring that, in this area, that self-interest works in the rest of the world’s benefit. It is also hugely important that Xi has committed, through the 14th Five Year Plan passed earlier this year, staggering amounts on research and development. With approximately 7% of GDP — more than 500 billion US dollars — being spent on different forms of research, much of it dealing with environmental sciences, China has placed its formidable financial resources in an area where, once more, the benefits will flow to the rest of the world, particularly if it succeeds in finding carbon capture technologies, or other forms of energy that can quickly and safely replace coal.

Xi’s expected absence from COP26, then, is far from the end of the world. He still styles himself as an environmentalist. Witness his attendance at a biodiversity summit in Kunming earlier this month: “We shall take the development of an ecological civilisation as our guide to coordinate the relationship between man and nature,” he said in his keynote speech.

Yes, recent power shortages in the northeast of the country have underlined the need for China to produce more energy. But the underlying imperative to protect the environment still holds for Xi. Achieving that while continuing to industrialise is unlikely to be easy — but that doesn’t mean cautious optimism is misplaced.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe