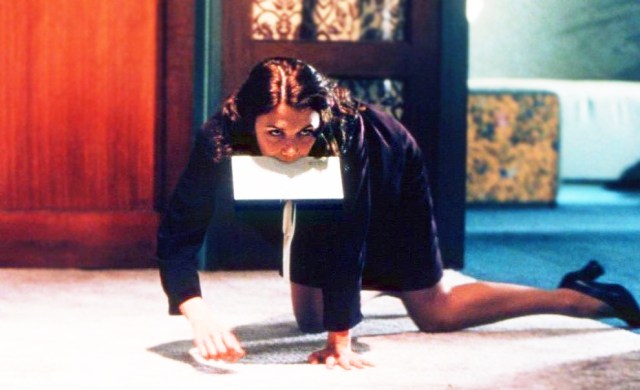

Sex won’t save us (Secretary, Lions Gate)

When I told Mary Gaitskill to read Michel Houllebecq’s first novel, Whatever, she replied: “You like that crap?” The next day she sent me a kind email recommending an energy healer. I didn’t take her up on the offer; I remained confused and disappointed that she’d been so unimpressed.

Before our call, she’d emailed me explaining that she wanted to talk about incels, and I thought that Whatever was the best book about them ever written: the world is divided into ugly and hot people who compete in ruthless combat, with no relief in marriage and no reward but rot. It’s obviously depressing — when I first read it, I immediately made my first (and for many years, last) therapist appointment. I was a 21-year-old living with my brother on Gainesville, Florida’s Sorority Row. I had no romantic prospects.

A few years later, I was in graduate school further north, in a contrived relationship with a cheerful Connecticut lawyer. In a cold and sunny condo, on the smooth wooden flooring, I read Gaitskill’s Bad Behavior: it was one of the only books about ugly women I’d ever read. There it was, again, but Midwestern and dumpy, not French and brainy: the sick sad world, where you might get laid but you’ll never get better.

Reading Gaitskill’s fantastic latest book, the essay collection Oppositions, I began to see why she’d reacted so badly to Houellebecq: he sounded simple, scientific, and therefore stupid. And Gaitskill doesn’t brook stupidity. Her terror and her grace — alongside her disorientingly good looks — is her intelligence; an elegant and icy one that, in the end, is also merciful. Throughout these astonishing essays about literature, music and more, she seems to be circling the notion that curiosity—embracing the muddle —is the path to empathy for sick, sad creatures like us.

Most of the essays in Oppositions are reprised from her 2017 collection Somebody With a Little Hammer. That title comes from her essay — included in both volumes — about teaching Anton Chekhov’s Gooseberries, with its famous speech: “At the door of every contented, happy man somebody should stand with a little hammer, constantly tapping, to remind him that unhappy people exist, that however happy he may be, sooner or later life will show him its claws, some calamity will befall — illness, poverty, loss — and nobody will hear or see, just as he doesn’t hear or see others now.”

Gaitskill serves as the person with the little hammer, but she doesn’t just remind us of unhappiness: beyond that, her job is to remind us how complicated living is, how little we know, how much we have left to do. Her job is to make us be adults.

That maturity — sometimes painful, often bleak — can prove unpopular, especially when it comes to sex. But here, Gaitskill is in a class of her own: braver, ballsier—just smarter. Twelve pages into an essay defending Lolita as a book about love, about how lovers strive for heaven and dwell in hell, she starts talking about how she was molested at five — and says she felt empathy for the man; that she was even aroused. Wow!

Anyone rushing to dismiss Gaitskill as unempathetic or cold would be hard-pressed: she inserts herself into these questions with unflinching bravery, and she knows suffering herself. But her “story”, like everyone else’s, is up for debate, and she doesn’t make herself a martyr or a hero. And her goal isn’t to condemn — not to condemn Mailer or Nabokov or her assaulters or the pretentious boyfriend obsessed with The Talking Heads: her goal is to complicate. Her goal is to change her mind.

She brings the same remarkable mixture of clear thought and startling vulnerability to questions of sexual consent: her essay “The Trouble With Following the Rules” is, for me, just about the best analysis of date rape ever written. It begins with Gaitskill’s description of her date rape as a sixteen-year-old girl dropping acid with strangers in Detroit, before questioning whether it was really rape. In a stunning turn, she says that when she was “raped for real” by an attacker who threatened to kill her, she got over it pretty quickly. Then, she writes about when a casual friend and her get drunk and he became aggressive and seemed almost to force her into sex.

In a move reminiscent of Amy Hempel’s The Harvest, Gaitskill writes: “In the original version of this essay I didn’t mention that when I woke up the next day I couldn’t stop thinking about him, and that when he called me I invited him over for dinner again. I didn’t mention that we became lovers for the next two years.” That first draft made the story simpler, but the messy version is braver and more true.

In Gaitskill’s vision, sexual partners have awkward, often painful, negotiations to make, often in the dark, often in a rush, often in confusion. And any decent, kind sex won’t come from rigid rules; it will come from, as she writes, “the kind of fluid emotional negotiation that I see as necessary for personal responsibility”. That negotiation may take years. By the end of the essay, she takes responsibility for pretending to consent, tripping in that apartment decades earlier, with that man who was poor and black and “high on acid and misunderstanding, just as I was”.

Gaitskill isn’t telling women to have lower standards for sex; in a sense, she’s telling them to have higher standards. In a remarkable piece on reading the Bible (“A Lot of Exploding Heads: On Reading the Book of Revelation”), she defines fornication not simply as sex outside of marriage, but as “sex done in a state of psychic disintegration, with no awareness of one’s self or one’s partner, let alone any sense of real playfulness”. It is a “primitive attempt” to “give ballast to the most desperate human confusion”.

Lately, outlets including the New York Times have been chattering about the idiotically termed “sex negativity”, supposedly in vogue among young women. However, after reading Gaitskill’s essays, it seems they’re not opposed to sex, but rather to what Gaitskill calls fornication.

“The Trouble With Following the Rules” is probably the best articulation of what, I think, women my age are so unhappy about: in the old sexual regime, the rule was for women to have as little sex as possible, and now the rule is to have as much sex as possible. But neither world really cares what women actually want or need, and in the new, supposedly liberated world, even if you aren’t date raped, as she says: “sometimes I did find myself having sex with people I barely knew when I didn’t really want to all that much.” Sex can be unpleasant or regrettable or confusing without being assault; with women under so much pressure and in so much pain, it’s hard to imagine otherwise.

As she writes, all people have a mixture of strong and delicate parts; part of them wants strange sex, while part of them flinches from it. Often, we want many things we can’t articulate at all: that’s what being human is. We all know that, and we all deny that as we tell students to fill out “consent forms” on their phones before sex.

Gaitskill is trying — alongside other books of this year, such as Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again and The Right to Sex — to make sex complicated again. Often, it’s neither pure, joyous, free-willed pleasure, nor felony rape. As Gaitskill writes in her sympathetic but clear-eyed essay on Linda Lovelace, the star of Deep Throat who later became an anti-porn activist, “I imagined that Lovelace simply lacked the confidence to describe what she did and felt in a nuanced way, and that the thing was very, very nuanced and contradictory. So she went with either ‘I liked it’ or ‘I was raped.’”

So many experiences are in between; in another anecdote, a woman in her fifties described how she was furious when she thought about how in her twenties, a man in the East Village would grab her breasts. But back then, she was giggly and flirted and loved attention. “So which is true, the giggly girl who just laughed when the guy grabbed her, or the angry woman in her fifties?”

Then she amps it up: apparently, some women orgasm when they are raped. What are we to do with this information? We live in a world of pain and compromise, and we need new language for “the sometimes excruciating contradictions that many women experience in relation to sex”. Without it, to quote her essay on the adaptation of Secretary (“Victims and Losers”), “every American has been “telling his her ‘story’ and trying to get redress for the last 20 years. Whatever the suffering is, it’s not to be endured, for God’s sake, not felt and never, ever accepted.”

Gaitskill accepts suffering. Perhaps that’s why girls my age love her so much. Gaitskill can see that even when we behave badly, we’re not just bad people making bad choices; we often don’t have good choices. We’re not sluts or evil or victims. We’re lost and lied to by everyone that was supposed to give us answers.

Too many of us, like the protagonist of Secretary, “yearn for contact in an autistic and ridiculous universe, and… wind up getting [our] butt spanked instead.” We know that sex won’t save us, that work won’t save us, we know that feminism won’t save us, and we don’t think the old rules will either. There’s a sense of doom.

The last thing Gaitskill said to me, as I was leaving her home last week, was that she thought she’d have been a very different person if she hadn’t been raised in Michigan. Perhaps that’s the Midwesterner in her — a sense that the world where safety and comfort were a promise, where if you made the right choices the right things happened, has already ended. We showed up late.

But there, too, she’s different from Houellebecq. She might be dark, but she isn’t mean. She sees that everybody is suffering, men and women, beautiful and ugly. We are all both villains and victims. Across these essays, she’s attuned to the way art and experiences people dismiss as upsetting or triggering are simply attuned to the complexity of life — to the way that love is a living nightmare.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe