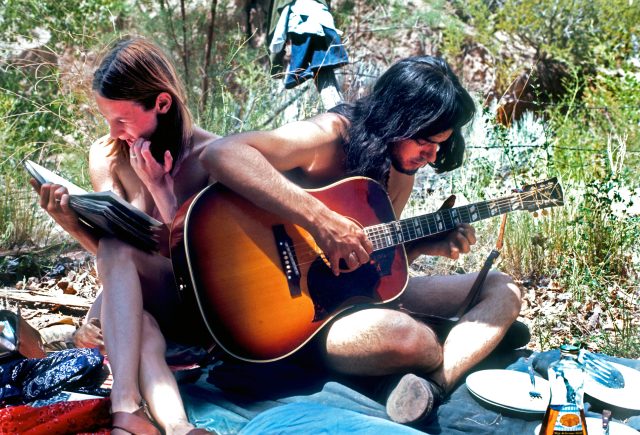

Credit: Robert Altman/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty

San Francisco was built on swamp and landfill. Mid-nineteenth-century settlers scuttled the hulls of the ships that had brought them to California and covered them with debris and sand, creating more land to build on. It was a ramshackle approach to construction, one that aligned with the every-man-for-himself atmosphere of this Gold Rush settlement.

And then, in 1906, an earthquake destroyed the fragile city. Buildings toppled. Broken gas pipes and fallen powerlines started fires. The authorities tried in vain to create firebreaks, resorting to dynamiting whole blocks of houses, but there was no stopping the fires that burned for another four days. More than 80% of the city’s buildings were destroyed. At least 3,000 people were killed, and the majority of survivors were displaced from their homes.

It is what followed the disaster, though, that is truly fascinating. San Francisco transformed. It went from a city renowned for cut-throat competition, race riots and brothels to the site of an extraordinary upsurge of public-spiritedness. Residents who survived built impromptu health clinics and makeshift shelters.

A beautician, Anna Amelia Holshouser, recalled how she and others stitched blankets and sheets together to make a tent for children, and then set up a soup kitchen, feeding as many strangers as they could out of a few unbroken plates and tin cans. All across the wrecked landscape, groups of survivors banded together to create places of safety and mutual aid. Rebecca Solnit describes the small-scale initiatives on each rubble-strewn street of San Francisco as “little utopias” — that is, idealistic micro-societies where people lived as much for others as for themselves, spontaneously rejecting the dominant narrative of individualism.

What occurred in San Francisco was a rare thing, but it had happened before and it would happen again. Over and over throughout history, idealistic, cooperative communities have sprouted up in the wake of disasters.

There are few examples as clear as the communities that followed the First World War, less than a decade after the earthquake in San Francisco. On a single day in the war — 22 August 1914 — the French army lost 27,000 men: half as many soldiers dead as the United States would later lose in the entire Vietnam War. In addition to ten million lives lost over the course of the conflict there was the wider damage: the uncounted millions scarred in body and mind; the disorienting sense of an entire social order destroyed.

People reeled under the compound effect of war and an influenza pandemic — robbed of their young, their hopes destroyed, uncertain of what the future held. But amid the destruction arose an impulse that was optimistic, energetic and humanitarian.

As in the aftermath of the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco, small groups of men and women began to rebuild, starting experimental settlements, renouncing old ways of living and trying to create new ones. Many people around the world believed the old social order was to blame for the Great War: the preoccupation with capitalist gain and nationalistic competition. Their response was to lead lives built around philosophies of non-materialistic mutual aid. In Germany, coteries of students and intellectuals took to the country to live collectively and farm cooperatively. In Japan, so many idealistic settlements were started that the conservative press reported anxiously on a “new village craze”. These post-war groups, though drastically different in style and structure, all had shades of the resilient, compassionate and communally-minded action that defined the days after the earthquake in San Francisco.

What can we learn from these reactions to disaster? Perhaps simply that adversity itself can prompt what is good in mankind — the urge to redraft the lines along which our societies are built for the better; a turn to co-operative social striving that would otherwise never have manifested.

And yet few utopias last long. In San Francisco, it was just a matter of days before thousands of soldiers were “restoring order” in the city — which included shooting those who were trying to collect food for the needy. New modes of living rarely spark large-scale social transformations, and all too often the status quo resumes.

But short-lived though most utopian communities are, they are connected in a beneficial way to the existing social order. They are in what German sociologist Karl Mannheim called “dialectical tension” with it: offering a reconfigured version of the outside world, expanding people’s sense of social possibilities, while at the same time being shaped by the mainstream’s needs. Even the communities that disintegrate quickly leave traces behind them, some of which are absorbed into the dominant social structures. And their examples gesture towards the fundamental idealism and resiliency in the human spirit, and the easily forgotten truth that it is always possible to recast the way we live.

We’re passing through another disaster now. And though the defining nature of this pandemic has been that people have been forced to live apart, it has nonetheless sparked impressive examples of idealistic activity, of cooperation and social action. Drivers in Wuhan created a volunteer car fleet to transport medical workers to hospitals when public transport shut down; young people in India mobilised to provide aid packages for those without savings; experts created the open-source library “Coronavirus Tech Handbook”, pooling knowledge on technologies and organisational methods for fighting the pandemic.

Climate change is a slower-moving crisis. Like the First World War, it has sparked in many a sense of the failure of the underlying systems of society and governance, which seem to be unable or unwilling to cope and change. Collectives experimenting with low-impact modes of communal living — ecotopias, as some of them call themselves — are proliferating.

At Old Hall Community in Suffolk, a group of 50 share a manor house, farming, cooking communally and keeping their carbon footprint as near as possible to net zero. In the mountains of Asturias in northern Spain, sixty Spanish, French, Danish and German women and men live in the remote commune of Matavenero, where they grow their own food, build their own houses and consume as little as they can. There are larger initiatives, including the community of Toyosato in Japan, where several hundred participants aim to demonstrate a fulfilling life built on sustainable farming, cooperation and minimal possessions. This settlement is one of more than 70 low-impact communities that form the Yamagishi movement, which stretches to Australia, Brazil, Switzerland and the United States.

These contemporary utopias are not a replacement for long-sighted national and international legislation, or for the much-needed regulation of corporate actors. In many ways they may be less effective than change-oriented activists such as Extinction Rebellion. But ecotopians put their money where their mouths are. They live in the way they think we all ought to live.

There seems to be a time limit on utopian communities. When the disasters that inspired them are forgotten, they generally collapse, or are absorbed back into the old order with its attendant oppressions and injustices. Sometimes, they mitigate that old order, demonstrating practices that can help make society a little better, a little more just. But climate change falls outside of this pattern. We are not likely to live to see the end of this global disaster. And if we insist on holding fast to the old order, to the dominant ideologies of hyper-individualism and materialism, the crisis will only deepen.

Utopian living, at its best, creates an opening in the fabric of society, allowing us to see how fragile the habits and structures which seem immutable in day-to-day life really are. “While the crisis lasted, people loved each other,” wrote the young reformer Dorothy Day of the San Francisco earthquake, having watched her mother give away her clothes to survivors. We haven’t quite reached the moment of imaginative, communal rebuilding that people are capable of when faced with disaster. We must hope that this moment will arrive soon.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe