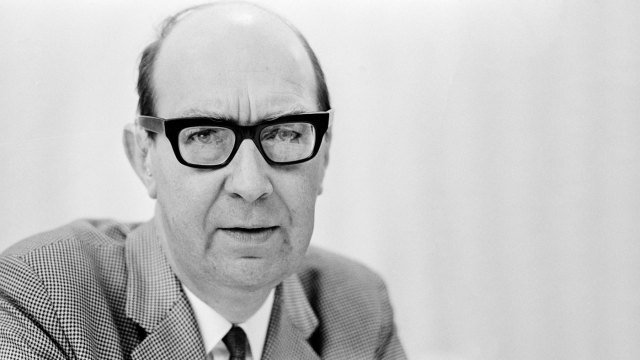

Who are you trying to decolonise? Credit: Barry Wilkinson/Radio Times via Getty Images

On a Friday morning in March 2020, I entered a secondary school for the first time since I had left for university. I was there for an interview. The opening was for a tutor, not a teacher: instead of handling a class of up to 30 students, I would deal with a small group of five students or tête-à-tête with just one student. I got the job that Friday afternoon, and would start the following Monday. A week later, Britain went into lockdown.

Schools closed and the summer exams were cancelled, but I kept my new job. It was a comprehensive school, and my brief was to tutor kids who were academically struggling through Google Meet, the fat and ugly cousin of Zoom. Because everything was up in the air, I was given free rein to teach the kids whatever I wanted that could reasonably be considered English Literature. So I decided to teach them about the poets I have enjoyed since I was little, such as Philip Larkin and Seamus Heaney. Those few months constituted one of the best periods of my life.

The OCR, one of the main exam boards in England, will remove the poetry of Heaney and Larkin (among other poets) from its school syllabus this September. Their justification is simple: the syllabus needs to be more inclusive and exciting. Heaney and Larkin are male and stale. They reflect a bygone era that doesn’t speak to an increasingly diverse classroom. They will be replaced by poets from British-Somali, British-Guyanese and Ukrainian backgrounds, and one of the first black women in 19th century America to publish a novel. 14 out of the 15 new writers added to the syllabus will be non-white. Jill Duffy, the chief executive of the OCR, stated: “This is an inspiring set of poems that demonstrates our ongoing commitment to greater diversity.”

This change is part of a wider movement to decolonise the curriculum. For too long, supporters of this movement argue, schools have deliberately excluded people of colour from the English canon and History textbooks. Just as ethnic minority people are discriminated against across society, they are marginalised in the classroom, and the latter injustice reinforces the former. One way to challenge this state of affairs is to decentre white, male authors, replacing them with writers who fall into other categories.

Jeffrey Boakye, the author of the recent book, I Heard What You Said, is a prominent advocate for decolonising the curriculum. Boakye, a black British man of Ghanaian heritage, argues that teachers should engage more vocally with race politics. For him, “being a non-white teacher is an inherently political position”. And the reason why the curriculum is “so unapologetically white is the arrogance of empire”. Our values, he argues, are rooted not in “scientific, political and industrial revolutions” but “in genocide, slavery and colonialism”.

Boakye is an English teacher. And English, according to the movement to decolonise the curriculum, should advance social justice. In his book, Boakye refers to one of his students, a black girl called Gertrude; he writes that after he taught her a poem called “Checking Out Me History”, by the British-Guyanese poet John Agard, she felt seen. “It spoke to her experience of a white education that didn’t speak to her sense of personal history.” The poem mentions figures from history like Toussaint L’Ouverture and Mary Seacole: we are supposed to believe it is great precisely because it celebrates black heroes.

The viewpoint of the curriculum decolonisers is based on the assumption that black students resonate most with poetry written by black poets. That is nonsense. Why should a black African student, for instance, identify at all with a poem written by a West Indian man? Because of their shared race? Race is not the only thing that defines the life and experiences of a person; I used to think only avowed racists believed it does. At a more practical level, why should a poem be taught if it can speak to students only on the basis of their being black: what about the Asian and white and mixed-race students in the classroom? This is not inclusion; it is division.

Decolonising the curriculum takes place at a superficial level, whereas I taught Larkin to my students because his poems move me at a visceral level: they convey the sense that, yes, this is what it is like to be haunted by fear and loneliness and impotence. And they do so with artistic virtuosity, using the right words in the right order to express such feelings. Consider these contrasting descriptions of death in his late masterpiece “Aubade”, both of them spot on but stylistically different from each other: the straightforward description is the “anaesthetic from which none come round”, and the more elegant version is:

The sure extinction that we travel to

And shall be lost in always. Not to be here,

Not to be anywhere,

And soon; nothing more terrible, nothing more true.

This is not a male or stale sentiment; this is a poem full of versatility and exactness, range and compactness. In other words, it is characterised by stylistic diversity, which should be a more relevant form of diversity in an English Literature classroom than the vagaries of skin pigmentation.

The poetry critic Jeremy Noel-Tod argues in a piece for the New Statesman that someone like Larkin should be replaced by the Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka. He writes that, “as a white teenager growing up in rural Norfolk in the Nineties, I wish my teachers had taken the chance to talk about the Soyinka poem in class”, because the Nigerian poet “might have helped us to understand structural racism as the scaffolding of the home country we took for granted”. If Noel-Tod wants to argue Soyinka is as good a poet as Larkin, fair enough, but his argument doesn’t reference art or merit. He is treating poetry as a sub-set of sociology — arguing that we should read non-white poets because they offer us insights into social and political issues.

If English is simply another variant of sociology or politics, why should the study of it be distinguished from these subjects? Sheffield Hallam University has recently been criticised for suspending its English Literature degree and incorporating it into a degree that consists of Literature, Creative Writing and Language. The justification for this proposal is that the study of English should serve a purpose, that it should have tangible benefits, such as enabling students to get a professional job. Many of the people who advocate for decolonising the curriculum might object to this, not recognising that they are also arguing that English should have a purpose — not getting students a job, but making them less racist. Even if they don’t officially want English to be assimilated into other fields of the humanities, like politics, in practice that is what they promote.

This is profoundly patronising to a writer such as Soyinka. He is the first African to have won the Nobel Prize for Literature. But a white poetry critic like Noel-Tod doesn’t value him for his artistry, but for his activism.

Black kids should study Larkin

Another problem with filtering literature through this rigidly ideological lens is that it disables the fundamental quality of any devoted lover of literature: curiosity. It stops us from reflecting on the particular cultural context of a poet or his poetry, and instead takes a reductive view of writers. Consider the case of Seamus Heaney: why should a poet who grew up in rural Northern Ireland, in a Catholic family, be seen as embodying the white, male British establishment? Ultimately, though, what matters to those who love Heaney and Larkin is not their identities; it is their expert manipulation of language.

I love the firmness of Heaney’s lyricism and his scrupulous eye. In “Blackberry-Picking”, for instance, he writes of both the joy (“You ate that first one and its flesh was sweet / Like thickened wine: summer’s blood was in it / Leaving stains upon the tongue and lust for / Picking”) and the darker side to this endeavour (“But when the bath was filled we found a fur, / A rat-grey fungus, glutting on our cache. / The juice was stinking too. Once off the bush / The fruit fermented, the sweet flesh would turn sour”). This is what ultimately distinguishes poetry, not communicating a direct message, but evoking a powerful sensibility.

Of course, a poet’s ability to do this does not depend on their race. The fact that great poets from non-white backgrounds are excluded from study is bad. But it is bad not because the identities of such poets are not being “centred”; it is bad because students are missing out on great poetry. Blindness to the artistic work of ethnic minority people is worthy of criticism, but assessing such writers on a tokenistic or ideological basis is another form of blindness: in both cases, the poetic merits of their work are ignored.

Those who support decolonising the curriculum see the relationship between non-white and white authors only in terms of conflict. They see it as a zero-sum game: we need to decentre white and male writers to empower writers from marginalised communities. But this underestimates the debt that many non-white authors owe to the traditions of Western literature. Writers are always in conversation with each other. Toni Morrison is renewing William Faulkner; Zadie Smith is renewing Dickens; Derek Walcott is renewing Homer. Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart was written in part as a rejection of Joyce Cary’s Mister Johnson and Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, but the title of Achebe’s novel is taken from a poem by William Butler Yeats and the plot resembles the structure of a Greek tragedy. There is some conflict between white and non-white authors in the canon, but there is also great continuity between these two groups. By ignoring this fact, Boakye is reinforcing an assumption anti-racists ought to dismantle: that to be Western is to be white.

W.E.B. Du Bois was one of the most influential radical black thinkers of the 20th century. But he also loved Richard Wagner. Du Bois proudly affixed himself to Western culture. As he put it, “I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not. Across the colour line, I move arm in arm with Balzac and Dumas. From out of the caves of evening that swing between strong-limbed earth and the tracery of the stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what soul I will, and they come all graciously with no scorn nor condescension.”

C.L.R. James, the Trinidadian Trotskyist, similarly affirmed an attachment to Western civilisation: “I didn’t learn literature from the mango tree,” he once wrote, “or bathing on the shore and getting the sun of colonial countries; I set out to master the literature, philosophy and ideas of Western civilisation. That is where I have come from and I would not pretend to be anything else.” In his dying days, when he was visited by Edward Said, James wanted to talk to Said about classical music rather than colonialism. When he died, James was called the Black Plato by the Times.

The traditions of Western literature and culture belong just as much to black people as white people. It is part of my inheritance. And that is why I loved teaching those kids: I was sharing what belonged just as much to them as to the kids with hundreds of books in their family homes or a private education.

My favourite student was a boy called Peter. I could tell from his surname that his family came from Ghana. He came to every single lesson, while all my other students found an excuse to skip at least a few classes. I never met Peter. I still don’t even know what he looks like; his camera was always turned off. But we cultivated a connection, not through the fact that both of our families come from west Africa, but by familiarising ourselves with the great works of English Literature. We read Larkin and Heaney, but we also read Derek Walcott. We read snippets of prose too — George Orwell and Toni Morrison and James Baldwin. The priority in studying James and Morrison was the elegance of their sentences, the effect of their imagery, and the sophistication of their tone. When we did approach the topic of racism, we had a foundation to build on. And all the time, I never felt the need to “decentre” white, male authors or slap on diverse voices for the sake of it. I was simply guided by what has moved me since I was a boy and continues to move me now: the transcendent beauty of great art.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe