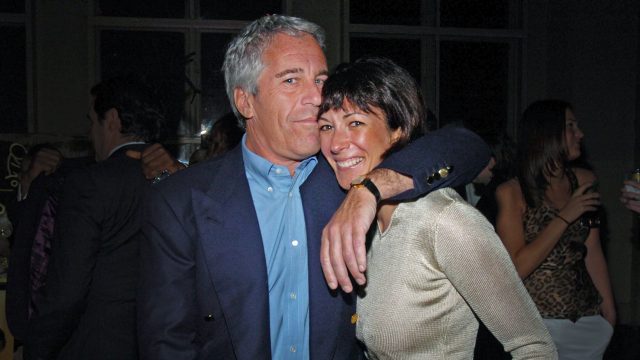

She didn’t have to be here. (Photo by Joe Schildhorn/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images)

If I were Ghislaine Maxwell’s lawyer, a job only slightly more desirable than being Prince Andrew’s valet, I would have spent most of my time at her trial painting a picture of her father. It’s true that the sheer Dorian Gray-like loathsomeness of such a portrait might have caused a stir. Some jurors might have fainted, while a few hardened police officers might have rushed out of court in order to throw up. Even so, I would have ploughed doggedly on, convinced that this was the most effective way to get my client off. Could the child of such a monster ever stand a chance?

Ghislaine was born with every disadvantage: extraordinary privilege, limitless resources, endless leisure, posh friends, inborn entitlement, and a repulsive beast of a father who seems to have bullied and indulged her by turns. Other people were born to do her bidding, while she herself was immune to accountability. She referred to the young women she exploited as trash. You don’t need to be a card-carrying Freudian to see that the man she pimped for, Jeffrey Epstein, was a surrogate father whose affection she could probably never depend on.

It wasn’t women of her age who attracted him. One unreliable father had already died on her, and another might metaphorically speaking do the same. In several of the photos of the pair, Maxwell is looking adoringly at Epstein, or even kissing him, while he is looking away or at the camera, apparently tolerating her devotion rather than reciprocating it. Desperate to continue as his partner in love, so I would argue in court, she was willing to become his partner in crime. People can do appalling things for the sake of love, but doing them for love is better than doing them out of cruelty or malevolence.

Was Maxwell fated to end up behind bars as a kid with a sexually abusive father and an alcoholic mother? Obviously not. Plenty of people with her upper-class handicaps turn out to be decent human beings. Maxwell didn’t have to inveigle young women into her lover’s massage room. That we amount to more than our circumstances is what we know as freedom. You can always act against the grain of your upbringing. It’s just that it can be fearfully hard to do so. Hangers and floggers aren’t wrong to think we have freedom of choice, simply blind to how arduous this can be. We are all free not to smoke, but a nicotine addict is less free in this respect than the Queen. If you want an image of freedom, don’t look at those who regard health and safety laws as fatal to human liberty; look at a man with a revolver who refrains from shooting the rapist of his small daughter.

It is only in the modern period that we start thinking of the will as a heroic force, one which overcomes our baser inclinations. It is thus that the idea of will power comes into existence. It is a matter of tensed sinews and gritted teeth. By contrast, for traditional thinkers such as St Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, the will is more a form of desire than a kind of power. On this view, to will to do something is to feel drawn to it — even, in the end, to love it. Far from struggling against what we want, the will has to plug into your deepest wishes if it is to work. Instead of a deep desire for heroin, you begin to feel an even deeper desire to be well. You embrace well-being because it’s enjoyable, not just because you’re likely to die if you don’t. Most addicts are aware of this possibility, but it rarely stops them from drinking or shooting up, just as nobody stops being a radical Islamist because somebody tells them they should.

The United States, true to its Puritan heritage, is a deep believer in voluntarism, regarding the will as supreme. That you’re responsible for absolutely everything you do is part of American folklore. It is this belief which puts so many of its citizens on death row. To point out that a lot of criminals were deprived and unloved as children is to sell out to determinism. The fact that there are degrees of responsibility goes unacknowledged. Freedom is as absolute in the judicial system as it is in the market place, and appeals to social conditions can be left to fancy-pants sociologists. Yet we wouldn’t have the concept of freedom in the first place, or know how to practise it, if we didn’t live in society. When Margaret Thatcher announced that society didn’t exist, she did so in the English language, which belongs to an individual only because it belongs in the first place to a particular civilisation.

None of this is to deny that Ghislaine Maxwell is a despicable predator who richly deserves her prison sentence. She treated the young woman she hired as a sub-human species fashioned to serve her own interests, much as her father treated his employees. Like the rest of us, however, she was also a victim of original sin, which is a more everyday affair than snakes in gardens or forbidden apples. St. Augustine was right to see that original sin is transmitted down the generations, though he was wrong to think that this was a genetic affair. His view of it is broadly at one with that of the poet Philip Larkin:

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

Larkin knew what he was talking about: his father was a fascist who supported Hitler, and Larkin himself was a racist and trade union-basher. The fact is that being born severely restricts your freedom. Nobody chooses to enter the world, or gets to select their parents. When a character in Samuel Beckett’s play Endgame protests to another character “But you’re my father!”, the latter replies “Yes, but I didn’t know it was going to be you”. Nobody chooses their body, their social status at birth or much of their temperament, a discomforting thought for a society obsessed with options.

All of this is set for us by our ancestors, hordes of whom lurk within our most casual gestures. It is impossible to say how many people there are in a relationship, but the parents of both partners are certainly at work there, and probably their grandparents and great-grandparents as well. The dead can kill us or drive us insane. The past is what we are mostly made of, and it lives on to stymie the present and future. So much for the excited chatter of brave new worlds and technological wonders.

Like Sophocles’s Oedipus, we are all guilty innocents, tainted by our origins. It’s notable that Oedipus, confronted with the fact that he has killed his father and married his mother, never once tries to defend himself by pointing out that he did all this unknowingly. For the ancient Greeks, guilt is an objective affair like disease or pollution, not in the first place a question of your intentions. And this is also true of the debt and guilt involved in our tangled inheritance. It infiltrates your bones and your blood whether you are conscious of it or not.

Characters in ancient Greek tragedy must move warily, as though picking their way through a minefield. Half-blind that we are, we can never know what damage our deeds will cause in the lives of others. Acts freely performed spin out of control and come to confront ourselves and others like some implacable destiny. It is this which the Greeks called Fate. Oedipus becomes a stranger to himself, while those who should be sexual strangers (one’s parents, for example) become intimate. In fact, there are no strangers, just friends you haven’t alienated yet. It would take a whole army of researchers to trace the consequences of any one of our actions, and some of them are very likely to inflict pain on someone somewhere. If we can’t move without hurting others, then simply to be alive is a question of guilt. There is a residue of harm built into social existence.

Original sin has to do with injuries of which we are innocent but are still in some sense responsible. Let’s say I sit on a bus and see the image of a desert island on a hoarding. The image begins to obsess me to the point where I abandon my family and spend the rest of my days lounging under a palm tree. Aghast at being deserted, my partner finds it impossible to carry on as a psychotherapist, with the result that one of her patients drowns himself in despair. Meanwhile, my daughter packs in ballet school and goes off to run a protection racket in Huddersfield. The culprit for all this is me; but the Malaysian workers who make spiral cuts on the bark of Para rubber trees to collect their milky latex also had a hand in it. Without them, there would have been no rubber to manufacture the tyres of the bus on which I was sitting. They are guilty innocents, bound up like the rest of us with those of whom they know nothing. All this is because Fate is a myth, and what we have instead is contingency: random collisions, collateral damage, unforeseeable effects.

The Larkin poem continues:

But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another’s throats.

“They” refers to one’s parents; and if it is true that the fuckers-up are also the fucked-up, forgiveness becomes possible. The misery your mum and dad handed on to you was a crippling legacy bequeathed to them as well. By recognising this, as the drug-addicted Patrick Melrose does at the end of Edward St Aubyn’s magnificent sequence of novels, you can break this deathly lineage, at least in your head and with any luck in your guts as well. It is a tragic process, however, precisely because the price of achieving sanity and fulfilment in these conditions is so fearfully steep. But if Melrose can do it, so can Ghislaine Maxwell in the quiet of her prison cell. In fact, it is all that is now left to her. We should remember that people who act abominably are usually under the influence of forces they can’t fully understand. But we shouldn’t allow them to get away with it either.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe