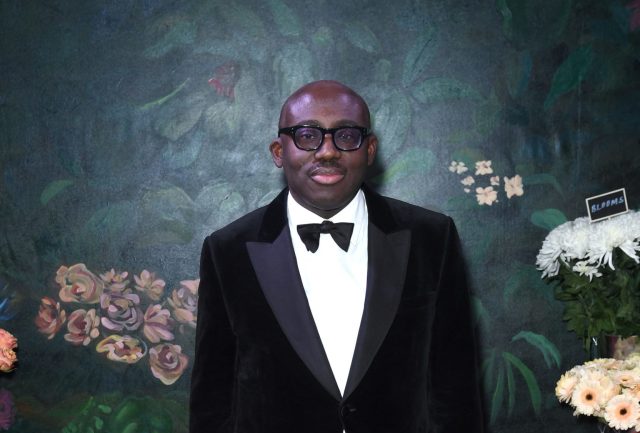

(Stuart C. Wilson/Stuart C. Wilson/Getty Images for The Business of Fashion)

Why are the models so thin? Why are the clothes so expensive? And what is the point of fashion? These were questions I had to answer pretty much every day for the decade I worked as a fashion journalist, and the same is true for every other person who works in the industry. Except one.

Fashion is generally seen as a frivolous and simultaneously dangerous industry, populated by airheaded Marie Antoinette-like characters wearing £10,000 hats, and malevolent figures intent on spreading eating disorders across the land. Over the years, I offered up various arguments in fashion’s favour: it’s a billion-dollar industry, it reflects the culture around us, everyone gets dressed and therefore engages with fashion on some level, and it is populated by hugely ambitious and successful women.

None made much difference, and the high-ranking women within the fashion industry — Anna Wintour, Isabella Blow, Donatella Versace — were snickered at as cartoonish stereotypes. It often struck me that the journalists who covered film (in which enormous expenditures and egos are the norm) or sport (hello, unattainable perfect physiques) never had to begin their articles by justifying their industry. Was this, perhaps, because fashion — unlike film and sport — is largely for women, and one of the last bastions of journalism dominated by women? Or did the fault lie with fashion itself?

I’ve been pondering these questions again over the past week as I’ve read the adulatory press around Edward Enninful, the editor of British Vogue for the past five years and Vogue‘s European editorial director for the past two. Enninful’s memoir, A Visible Man, is being published today, and it comes festooned with quotes from Salman Rushdie and Kate Moss (“What fun!”) The reviews have been determinedly positive, albeit in a glass-half-full kind of way (“Happily his book is better than his interviews” – The Times). He scored the double whammy last weekend of being the cover interview for The Sunday Times Magazine (“How Edward Enninful became the king of fashion”) and The Observer Magazine (“The most important man in fashion”).

He is, as all the press has taken pains to stress, the first black and gay editor of British Vogue. He is also — although this has been less commented upon — the first man.

Coverage of Enninful has focused almost entirely on who he is rather than what he does. He was born in Ghana, moved to London as a child and was hired as a model in his teens. He became fashion editor of i-D when he was only 18, much to his family’s horror, and now here he is, editing one of the most important fashion magazines in the world. It’s an extraordinary story, but not a wildly unimaginable one in the fashion industry. John Galliano is another gay working-class immigrant who made it big in London fashion at an early age, Alexander McQueen was a gay East-Ender who did the same. Naomi Campbell is the daughter of a single mother from Lambeth. Alek Wek moved from South Sudan to London in 1991 and was soon after hired as a model.

As Enninful writes in his memoir, “Fashion is a borderless industry that is powered by immigrants. As I looked around New York Fashion Week in early March, I saw how 90 per cent of my colleagues living and working there were originally from other countries.” None of this detracts from Enninful’s enormous achievement, but fashion, and particularly British fashion, has been better at embracing immigrant, gay and working-class kids than outsiders give it credit for.

The little discussion there has been about what Enninful actually does has focused on how he has improved diversity in fashion. There is no doubt there are more black models and features about race and LGBT issues than ever before in Vogue, and this reflects the time as much as it does Enninful himself. There has been much comment on how different his Vogue is from his predecessor Alexandra Shulman’s, which was largely, and even infamously, white and posh. (I was briefly a contributing editor to Shulman’s Vogue, although she then let me go, so I have no loyalty to her.)

Enninful has brought identity politics to the magazine, but it’s always interesting which parts of someone’s identity count and which don’t. For example, Vogue now features models such as Cara Delevingne and Adwoa Aboah talking about, respectively, sexuality and race, and Meghan Markle edited a special issue. Quite how much of a change these women are from the posh ones of yore is a debatable issue, given Delevingne and Aboah are descended from aristocracy and Markle is married to a prince. And of course, the models are just as skinny as they ever were, and the clothes just as expensive. Last month’s cover celebrating Pride featured LGBTQ young people, but it was indistinguishable from any other Vogue cover, given they were all beautiful and thin. The current cover features Linda Evangelista, airbrushed to near unrecognisability and almost entirely covered, lest anyone be offended by her 50-something flesh.

It must be a strange time to be a fashion editor. We are entering the worst cost of living crisis in most people’s living memory. The mental health of girls and young women is notoriously precarious, with rocketing rates of depression, body-hatred and self-harm. When Shulman was editing Vogue during the 2008 financial crash, every interview she gave included questions about what possible relevance Vogue had now, and I doubt she got through a single day in which she wasn’t asked by a journalist whether she felt responsible for anorexia. None of these subjects has been raised in the press around Enninful, who — lest anyone has forgotten — edits a magazine that exists to sell expensive clothes and feature very thin and beautiful women. The coverage has been entirely about him and his triumphant story. It has barely mentioned who Vogue is actually for.

In his memoir, Enninful recalls the speculation about whether he would be made editor of Vogue: “The fact that I was Black and gay was a big focus. My even being considered was presented as shocking. Hard not to see the connotations: this one doesn’t belong. I was well used to it, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t hurt every time.” And of course, that’s true. But it’s a lot more likely that he was seen as left-field choice because of his sex rather than his race or sexuality. After all, the fashion industry is not exactly short of gay men, and there have been high-profile black fashion editors before Enninful – although not at British Vogue — including André Leon Talley at US Vogue, Michael Roberts at Vanity Fair and Robin Givhan at The Washington Post, the first fashion writer to win a Pulitzer.

Editing Vogue, though, had always been done by a woman. Not any more. You can argue that this is a good thing and jobs should be open to all genders. Yet Vogue is a magazine about women and for women, and now a man is in charge of it. Shulman edited GQ before she got the Vogue job and she was regularly asked how she knew what men wanted. When some wondered how he would know what women want, he said in an interview with the New York Times last month, he called his friends “Rihanna and Naomi, and they both told me, you just have to tune it out”.

After questions about skinny models, pricey clothes and fashion’s pointlessness, the fourth inevitable question was whether it was just an industry in which gay men dictated what women should wear. I always bristled at this, with its blaring overtones of homophobia. Enninful’s sexuality is not relevant to his ability to do his job. But his sex is surely a different matter, given he is editing a magazine for women. He has said “I never think in terms of sex or gender. I think in terms of what someone is bringing to the table.” This is the kind of statement only a man can make. In all the glowing press about Enninful’s identity, his sex — as a critique — is mentioned about as often as the fact that Delevingne’s godfather is Nicholas Coleridge, the former long-term chairman of Condé Nast. Which is to say, not at all.

Fashion is a joke. It’s an art, sure, and a hugely lucrative industry. But it’s also absurd: all these ludicrous clothes and accessories churned out month after month and then draped on bizarrely proportioned women in order to sell them to the trollish masses. Anyone who works in it knows that it’s a bit silly, which is why it’s so difficult to argue against the piss-takers. If fashion is referenced at all in the mainstream, it is usually done so sceptically and satirically, Devil Wears Prada-style.

But there is no satire in the coverage of Enninful, even though his book offers plenty of opportunities for it, with his talk of “intelligent” dresses and his gush about Beyonce (“I can’t help thinking how all these walls that we perceive Beyonce putting up don’t exist to facilitate ego”). He is surely the only fashion editor in existence who is not snarkily asked in every interview about the prices of the clothes and the waist measurements of the models in his magazine. Instead, the tone around him is hushed, earnest and reverent. Some will say this is fair enough, given his background; Wintour and Shulman are both posh and white and therefore able to take the barbs.

But you can’t have it both ways: saying Enninful is the king of fashion, but also so fragile he must be wrapped in cashmere. Also, he has been working in the fashion business for more than 30 years; he got married at Longleat with Campbell, Moss and Victoria Beckham in attendance. When the New York Times asked him for the names of five friends they could contact when writing a profile of him, his list was “Beyonce, Rihanna, Naomi, Imam, Oprah.” He is more ensconced in the fashion establishment than Shulman ever was.

When I used to insist that fashion reflected the times as much as film or art or literature, people would laugh: of what possible connection to the common man could a £12,000 dress by Armani have? And at times, I questioned this myself. But the coverage around Enninful takes it as a given that he is overhauling the culture through Vogue, producing “a massively visible new idea for what Britishness could mean”, as he puts it in his book. Enninful’s Vogue is only a force for good, whereas everyone else’s, it seems, was and is toxic. Maybe. Or maybe the only way people can take women’s fashion seriously is if the person in charge is a man.