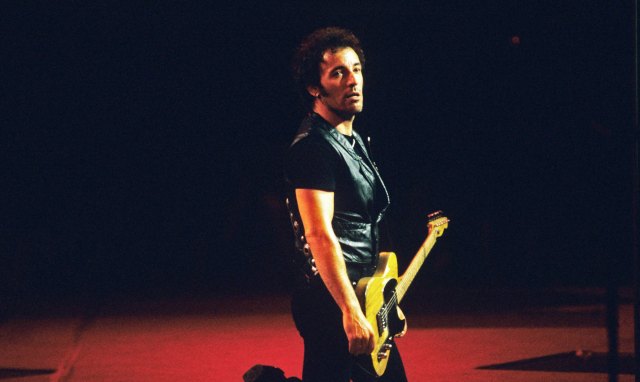

Mr State Trooper (Brooks Kraft LLC/Corbis via Getty Images)

In 1982, Bruce Springsteen was at the height of his powers. Seven years earlier, his third album, Born to Run, had brought him global fame. “Springsteen is everything that has been claimed for him,” declared Rolling Stone. Critic Dave Marsh said he was “comparable to all the greats”. John Rockwell called him “the next Mick Jagger”. His next two albums, Darkness at the Edge of Town and The River, did nothing to dim his blazing star.

In a period of intense creativity, Springsteen wrote hundreds of songs for a much-anticipated follow-up. Intending to teach them to his band, he recorded them on a simple four-track tape machine in his New Jersey bedroom. Subsequent sessions in the studio could not replicate the intensity of these demos. They were too personal, immediate: the words often mumbled so softly they were barely discernible; the rhythm of the guitar-playing often broken. But rather than re-record these tapes himself, Springsteen released them, as Nebraska.

Everything about the album went against the spirit of the times. Ronald Reagan was two years into his first term after the Republicans swept the working-class heartlands of America in a landslide victory. The president believed storybook myths about his country: that its fortunes had been made by pioneering men and women on the western frontier, free from the restraining hand of the federal government. Reagan’s America was like the cowboy B-movies in which he had once starred: a land of heroes, opportunity, and sunny Hollywood optimism.

Nebraska was not optimistic. Its cover sleeve depicts a bleak sky, above a road to nowhere, ice on the windshield and, beneath it, the title in red, like a warning sign. It sold poorly and due to its troubling themes, Springsteen did not take it on tour. Nebraska was left to speak for itself. Today, exactly 40 years after its release, that voice is no less disquieting. Its characters are mostly out-of-work men, driven to the edge of madness, and sometimes beyond it, by poverty and despair. They commit petty acts of crime to make ends meet, or sometimes shocking acts of depravity.

The album’s opener, for instance, tells a fictionalised account of the crimes of Charles Starkweather, a 19-year-old carpenter’s son who took his 14-year-old girlfriend on a killing spree around rural Nebraska in 1959. “I can’t say I’m sorry for the things we done,” reflects Springsteen’s Starkweather character, “at least for a while, sir, me and her we had us some fun.”

On Nebraska, Springsteen’s characters all speak in this idiomatic, first-person style, punctuated with “sirs” and “misters”. They speak in parables, of gleaming mansions on hills, of lost sons returning to fathers, of family loyalty chosen over duty. The economy of language owes much to the influence of Flannery O’Connor, the writer of Southern Gothic fiction, in whose profoundly Catholic vision grace is often found in moments of shocking violence. “She got to the heart of some meanness that she never spelled out,” Springsteen has said, inspired to create characters of his own. Her work, he later reflected, reminded him of the “unknowability of God”.

Matters of the soul were on Springsteen’s mind. He was 33 and mired in depression. It was an affliction that ran deep among the Springsteens, working-class Italian-Irish Catholics from Freehold, New Jersey. Bruce’s father was a brooding, sometimes violent alcoholic, who traded various blue-collar jobs. Nebraska is Springsteen’s most personal album, written for the kitchen in which his father drank; for the “flat, dead voice” that drifted through his town on sleepless nights; for his grandparents’ sparse living room, frozen in time, ornamented by a picture of his father’s sister, killed as a child in a bicycle accident.

Springsteen grew up introspective with few friends or prospects. Music, to which he devoted his life, offered salvation. Greetings from Asbury Park, his first album, is about the hot summer streets and beaches of New Jersey; Born to Run and Darkness on the Edge of Town reflect dreams of escape; while on The River, Springsteen begins to explore working-class lives and problems. It is on Nebraska, however, that these themes reach full maturity. It is the moment he steps into his father’s clothes and channels the working-class consciousness of America.

It was Springsteen’s preternatural artistic gift that his own depression offered a way to explore his country’s, which, by the early Eighties, had grown acute. Between 1945 and 1973, the average American family income almost doubled. In the factories of the Midwest, rising wages meant harmony between unions and management. Blue-collar workers reaped the fruits of their labour. They bought houses, cars, and household goods once considered luxuries reserved for the privileged few.

However, by the mid-Seventies, a combination of sluggish economic growth and high inflation brought this period of relative prosperity to an end. The Reagan government prescribed a shock therapy of tax cuts and deregulation. Unemployment reached 10.8%, a postwar record. High interest rates led to home repossessions. The factories of the Midwest began to rust. The result was the hollowing out of small towns, the breakdown of families, and diseases of addiction and despair.

It is into these broken lives that Nebraska casts us. “Down here it’s just winners and losers and don’t get caught on the wrong side of that line,” says one character, bound for Atlantic City, the promised land. But so often Springsteen’s characters are caught on the wrong side, like the worker who loses his job at an auto-plant and murders a store clerk. “Now I ain’t sayin’ that makes me an innocent man,” he tells the judge. “But it was more ‘n this that put that gun in my hand.”

Nebraska is a place where fates are decided, where confessions are made, where redemption is sought. A driver begs a late-night radio DJ to hear his prayers, a highway patrolman drives down to the crossroads, an out-of-work man agrees to do an unspeakable favour. These men are haunted by the past. Ghostly voices rise from moonlit fields. Radios are jammed up with “lost souls callin’ long distance salvation”. A bar band sings “The Night of the Johnstown Flood” — not a song, but a tragedy, which claimed the lives of 2,000 Americans in the late 19th century.

And Nebraska becomes not a state, but a state of being: a purgatory of perpetual darkness where its characters are condemned to the horror of eternal recurrence. Whether there is any escape from the bardo is not clear. A character dreams of his “father’s house”, which stands “hard and bright” across a dark highway, visible, but out of reach. The album ends with the optimistic line: “every hard-earned day people find some reason to believe”. But the song is about lives of quiet desperation and pain.

In the early Nineties, doctors discovered millions of Americans were suffering from a mysterious pain. The pain was especially acute in the Nebraska of Springsteen’s imagination: the desolate farms and villages, the hollowed-out factory towns. Doctors did not know its source, but there were many causes. Since the Seventies, the wages of white working-class men not only flattened, but declined. As factories shuttered, trade union membership collapsed. Marriage and fertility rates fell much faster than the rest of America. Church attendance fell too. And while the American crime rate has decreased since the Nineties, in the Rust Belt it remained persistently high. Bereft of hope, men and women in these godforsaken places fell victim to diseases of despair: drug addiction, alcohol abuse, suicide.

Then, in the mid-Nineties, a solution for the pain was found: painkillers. Because the pain could not be treated at source, it was numbed. Opioids were prescribed to millions of Americans. Big Pharma companies grew rich, while patients were immiserated. Because patients developed a tolerance to the drugs, they turned to alternatives bought on the street, some 100 times stronger than morphine. Between 1999 and 2017, the death rate in overdoses from opioids increased fivefold. But the pain remains. And the economic conditions — high inflation, high interest rates, low growth — that were among its causes, have returned. The American heartlands of 2022 are no less a likeness of Springsteen’s Nebraska than they were in 1982.

It is these abandoned heartlands Nebraska still speaks for. It speaks for their dead, too, many of whom, awaiting final judgement, are trapped there, between this world and the next.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe