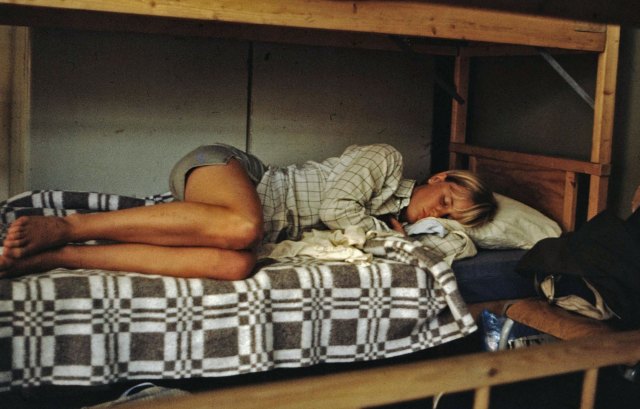

Is sleepwalking insanity? (Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images).

When is a rape not a rape? When the perpetrator is asleep. In the summer of 2003, a mixed group gathered at a grand house in the Beaches district of Toronto. It was an annual thing — a house party and croquet tournament. At about 4am, the previous year’s champion — a well-liked 32-year-old man — collapsed on the sofa, exhausted and drunk. He fell asleep. Nearby was a young woman, also sleeping. An hour later, the woman awoke to find her underwear removed, and the man, who she had not met, having sex with her. She screamed and pushed him off. He got to his knees, dazed and incoherent — “like when you’ve just woken them up out of a sound sleep”, in her words. She demanded to know her attacker’s name. “Jan”, he told her, truthfully.

It was not long before this that the neuropsychiatrist Dr Colin Shapiro had coined the term “sexsomnia”, and it was he who carried out a thorough investigation into the incident. He interviewed the defendant’s friends, family, and ex-girlfriends, and monitored his brain activity while sleeping. At trial, he expressed the view that the attack had been committed during an episode of parasomnia, otherwise known as sleepwalking. Several well-known triggers were present: alcohol, exhaustion, emotional stress.

The prosecution denied that the attack had been involuntary, but did not call on any other expert to contradict Dr Shapiro. The judge agreed with the defence, and the defendant walked free. A judge in the Court of Appeal, which examined the case comprehensively, deemed sleepwalking attackers “one of the most difficult problems encountered in the criminal law”. A sleepwalking victim is perhaps an even more troubling proposition, because a further question arises: could there have been a “reasonable belief in consent”? And can a complainant suspected of sleepwalking be expected to provide contact details of ex-partners, or submit to intrusive testing? One case of a sleepwalking victim — or so the defence argued — is the subject of a recent BBC documentary, Sexsomnia – case closed?

The facts are similar to the Canadian croquet case. Jade McCrossen-Nethercott — who has waived anonymity — fell asleep on a sofa at a small London house party in 2017. She had not drunk a great deal. When she awoke, she felt as if she had been penetrated. Her trousers and underwear were off. The man responsible was beside her. She challenged him. He said he thought she had been awake.

The documentary tells the story of her contact with the criminal justice system following this horror. We are shown an extract from her video-recorded account to police, in which she discloses a history of parasomnia. The defence, seeing this, instructed a sleep expert, who said there was “a strong possibility” of “sexsomnia”. But the phrase “strong possibility” comes from this media report; the documentary puts it much lower: “consistent with”. This is not the only piece of apparent one-sidedness in the programme. When we are played the recording of the Crown Prosecution Service lawyer telling Ms McCrossen-Nethercott that they are going to drop the case, the clear impression is given that the decision was based on only a single expert report, from the defence.

In fact, as is later written in a super-imposed caption, there was a report from a second expert. Not included in the caption is the fact that the report was commissioned by the Crown itself. An expert’s first duties are to the truth, and to the court, but it is not uncommon for bias to creep in. So it was quite proper for the Crown to obtain a second opinion — which, it turned out, also supported the “sexsomnia” theory. If I were the defence lawyer in a case like this, armed with two expert reports that suggested a real possibility of sleepwalking, I would be feeling very confident. As the CPS explained to Ms McCrossen-Nethercott, the expert reports meant that the evidential threshold of a 50% chance of conviction was no longer met. The court duly recorded a Not Guilty verdict. There would be no trial.

But Ms McCrossen-Nethercott challenged the CPS’s decision. In particular, she felt that the strength of the sexsomnia contention was not enough to end the case before trial: there was no evidence that she’d engaged in sexual activity during any of her previous sleepwalking episodes. One of the experts had said that this could have been her first episode. Ultimately, the Chief Crown Prosecutor who performed the review agreed with Ms McCrossen-Nethercott: these difficulties should have been examined in court. Small comfort, of course, when the defendant had already been formally acquitted. Ms McCrossen-Nethercott is now suing the CPS.

Her case is thought to be the first in which the complainant’s alleged parasomnia, rather than the defendant’s, is central. But there is no doubt that sexsomnia exists, and is not all that rare among those who sleepwalk. And although it is about three-times as prevalent among men as it is among women, it certainly affects both sexes.

In an appearance on Woman’s Hour, the director of Sexsomnia — Case Closed? said she had found about 50 cases over the last 20 years in which the issue has arisen. In one of them, a young Yorkshireman was acquitted of raping a woman in his flat on the expert evidence of Dr Irshaad Ebrahim. It was slightly disappointing, therefore, to see Dr Ebrahim in the documentary telling Ms McCrossen-Nethercott that “there are a lot of lawyers trying to get business out of it [i.e. sleepwalking defences]… The ones who are enabling it are the ones who are advertising they can get you off”. A lawyer with experience in this niche area must surely be permitted to advertise their competence — how else is an innocent sexsomniac to choose a representative? And I doubt many, or any, lawyers are claiming that they can use the defence to “get you off”.

Other 21st-century parasomnic rape acquittals include an RAF serviceman, who in 2006 had sex with a 15-year-old girl after a party, and whose longstanding somnambulism earned him the nickname “nightrider” from his colleagues; a drama student who had sex with a non-consenting woman at a house party in 2008; and a roofer who in 2007 had sex with his friend’s wife after a barbecue. All these cases, and many others like them, have one startling thing in common: the defendants were acquitted entirely, with no requirement to submit to treatment, or to avoid the triggers that increase the chance of parasomnic attacks occurring.

And this is the issue that the Ontario Court of Appeal had to grapple with in 2008, after the croquet party acquittal. The trial judge’s finding that the attack had been involuntary was not open to challenge. But the prosecution argued on appeal that he had been wrong to find that parasomnia should result in an acquittal; rather, they said, he should have been found insane — and therefore liable to be detained. The Appeal Court agreed.

In Canada, as in the United Kingdom, the law divides involuntary acts into two separate categories of automatism: insane, and non-insane. And there were two recent precedents on how this should be done. First, R v. Parks (1992), in which a sleeping man drove ten miles to the home of his mother-in-law and bludgeoned her to death with a steel tyre lever. There, the Supreme Court had upheld the finding of non-insanity. Secondly, R v. Stone (1999), in which a man stabbed his wife 47 times after suffering an abusive tirade (she said, he claims, “that she couldn’t stand to listen to me whistle, that every time I touched her she felt sick… that I had a little penis and that she’s never going to fuck me again”). The judges in that case shifted the law firmly in the direction of insanity for such cases.

The Supreme Court in the croquet case expressed the view that part of the reason for the shift in Stone had been the contemporaneous softening of the sentencing options available for “insane” defendants. The Court in Parks, they noted, had had an understandable reluctance to condemn a sleepwalker to indefinite detention in a mental institution. Post-Stone, however, outcomes became more flexible.

Here, “insanity” in the criminal law requires a “disease of the mind” — an outmoded phrase from an 1843 opinion of the UK Law Lords — but neither concept matches any medical definition. The legal distinction between insane and non-insane automatism has been described in various different ways over the years, but the real nub of it was captured by Mr Justice Bastarache in Stone: “The fundamental question … at the centre of the disease of mind enquiry [is] whether society requires protection from the accused.”

And so it should be. But in the United Kingdom we do not seem to have caught up. In 1991, in a case in which a 32-year-old man attacked a young woman he fancied with a rock and a video-recorder, apparently in his sleep, the Court of Appeal held that sleepwalking violence should generally be regarded as insanity rather than automatism. But as press reports of sexsomnia acquittals suggest — and as the Law Commission has since confirmed — common practice in the trial courts is to allow verdicts of non-insane automatism for sleepwalkers, as if they are no threat to society.

Automatism is better for the defendant in terms of outcome — acquittal rather than detention in a mental hospital — but also because of the different burden of proof. A mere doubt is enough for a non-insane automatism acquittal, whereas the defence have to prove insanity to be likely. There are, therefore, sound conceptual and public protection arguments in favour of treating sleepwalking as insanity. (Not that it would have helped Ms McCrossen-Nethercott: the defendant cannot be expected to disprove the absence of reasonable belief in consent.)

If we did treat sleepwalking as insanity — as many argue we should — there would at least be the possibility of giving violent sleepwalkers medical and other treatment, forcibly if need be, in order to protect the public. The case of former soldier Joseph Short illustrates the potential benefits of this approach. Short was accused of a 2011 rape in Scotland, but the Crown dropped the case after leading expert Dr Colin Espie supported a diagnosis of sexsomnia. He was then tried in Hull for a further rape, and acquitted on the same grounds. In 2016, he was tried in Birmingham for another two sex attacks.

This time, he was convicted, and received a 15-year extended sentence. Dr Espie had new evidence to give: Short had not followed his advice on how to reduce the risk of a sexually violent parasomnic episode. But some more formal constraints on his freedom might have saved Short’s later victims, assuming (which we should not) that he was in fact a somnambulist rather than a lying rapist from the start. In 2013, the Law Commission recommended a wholesale reconsideration of the law in this area. It has not been followed up. There is no evidence of an epidemic of false sexsomnia defences, but such cases ought to be dealt with consistently, and with public protection foremost in mind.

The law’s response to one of the earliest well-documented cases of violent sleepwalking may serve as inspiration. In 1843, a doting father, 28-year-old Simon Fraser, got up in the middle of the night, picked up his 18-month-old son, and killed him by repeatedly smashing the boy’s head against the walls and floor. He thought he had been fighting a monster. The jury found him not guilty, and — following some dispute between experts — not insane. There was, however, according to some reports, an informal arrangement agreed: for the rest of his life, his wife would lock him in his bedroom at night.

But these days it might be best if the Courts could deal with those who commit involuntary violence by subjecting them, in appropriate cases, to the enforced supervision of medical professionals and probation officers. It is unwise to leave even an accidental rapist’s remedy to his own sense of personal responsibility.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe