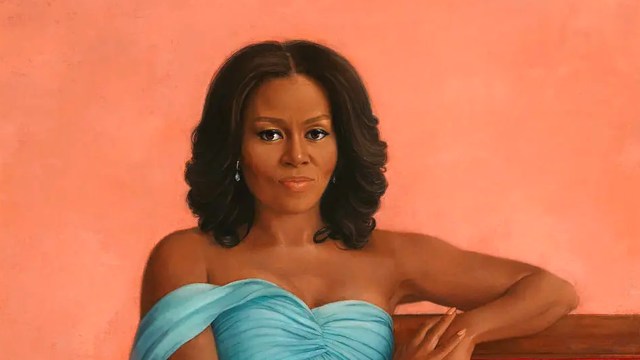

She’s not what you want her to be. Credit: Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images

Michelle Obama has always been surrounded by ghosts of herself, each one a projection of someone else’s fears or fantasies. She was a terrorist fist-bumper. She was a fashion icon. She was a shrill liberal scold or the original girlboss or a tireless activist. She inspired hopes and fury and even pop songs — her name is so synonymous with a certain sort of confidence, competence and glamour that when Fifth Harmony sings, “I’m on my Michelle Obama” in their 2015 song “BO$$”, you know exactly what they mean — even though, as a sentence, it makes no sense.

Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that certain folks want to see her run for president — or are terrified that she will. One article by former GOP creative strategist Myra Adams called Mrs Obama the Democrats’ “break-glass-in-case-of-emergency-candidate”, noting that her “limitless” fundraising ability and “winner’s aura” would make her not just a frontrunner in the primary but an uncontested one whom no other Dem would dare challenge. Meanwhile, presented with the prospect of a 2024 Michelle Obama candidacy, one anonymous Right-wing activist gasps: “God help us.”

Luckily for Republicans, God need not be involved; Michelle Obama has been unequivocal about her total lack of desire to run for office, recently saying that it’s the one question she detests above all others.

But, then, the eagerness surrounding the idea has little to do with Obama herself and lots to do with an overall sense that the wives of presidents, at least the Democratic ones, are not just political spouses but political spouses. This is partly to do with Hillary Clinton being the first FLOTUS-turned-aspiring-POTUS, but perhaps more to do with the prevalent (and not necessarily incorrect) sense that women can and should be doing more in the world than standing behind a man, even if that man is the leader of the free world. Gone are your grandmother’s first ladies, baking cookies and hosting social events and carefully choosing their pet projects from a pre-selected list of distinctly feminine causes. Dissolved is the unofficial role of America’s Homemaker-in-Chief.

Michelle Obama is, indeed, like no other First Lady before her — but this includes the ones who came right before her. Her new book, The Light We Carry, is less a political memoir, than an inspirational guide; certainly it could not be farther in tone or subject matter from Hillary Clinton’s What Happened, a grim post-mortem on her failed 2016 run for President. Over the course of 10 chapters, Obama emphasises communication, connection, and common humanity; she reflects on her role as a wife, a mother, a daughter, and a friend. The whole thing is unmistakably and unabashedly classy, to the point where if Obama recalls any of her predecessors, it’s more Jackie Kennedy than Hillary Clinton: a person without leadership aspirations who nevertheless ends up leading by example.

Michelle Obama’s values and principles are classically liberal, which is to say they’re out of style on the Left — dismissed as respectability politics by people whose preferred political setting is level-11 rage. Publicity seems to nod to current progressive pieties: the blurb promises a look at “issues of race, gender, and visibility”. In it, Obama does occasionally use language that feels borrowed from more polarising authors (the term “black bodies” appears here and there, as if it accidentally wandered into the text from an adjacent book by Ibram X. Kendi), but these elements are far less prominent than one might imagine — or than the media’s insatiable hunger for stories of racialised conflict might make it seem.

The most striking thing about the book is how consciously she veers away from the divisive framing that’s such a hallmark of Left-wing political discourse in 2022. “Most of my earliest memories of being different have nothing to do with being Black,” Obama writes early on in the chapter, “Am I Seen?” Being black did eventually make Obama different, and she does eventually get to this part. But as a child in a largely-black Chicago school, she stood out not for the colour of her skin but her height.

Obama was a tall child. It made her at once hyper-visible and easily dismissed — always in the back row or last in line, owing to the obsession among elementary school teachers with lining up students from shortest to tallest. She describes the moment of dismay she experienced as a high school student watching the cheerleaders tumble across the basketball court and realising that “some of those girls were approximately the size of one of my legs”. (Obama, like her husband, unlike her predecessor, can be very funny.) What’s remarkable here is the relatability. Who among us didn’t experience a moment like this in the throes of puberty: a self-consciousness so heightened that your very existence seemed like an embarrassment too awful to bear?

It’s to Obama’s credit that she gives this credit to her audience: she knows they’ll nod along, recognising their own experiences in hers. This shouldn’t be a significant thing for the memoir of a high-profile Democrat to do — but it is. Operating in a sea of awareness-raising tomes, whose readership is meant to include many if not mostly white women, she is a rare thing: an author who treats those readers charitably rather than with scathing contempt. She gives them the benefit of the doubt, not just that they are capable of empathy, but also that her own experiences are universal enough to empathise with.

If not for the fact that the term has already been coopted to describe a very different sort of ideology, you might even say that Obama’s attitude is inclusivity made manifest: an insistence that humanity recognises humanity, across boundaries, in spite of our differences. “I think the most we can ever do, really, is to walk partway across the bridge toward another person and feel humbled that we get to be there at all,” she writes.

And so this book, against the backdrop of contemporary American politics, does begin to seem like a political legacy of sorts, in spite of itself. It’s impossible not to notice echoes in The Light We Carry of the same pragmatism — and sometimes exasperation — that Barack Obama has exhibited in recent years when critiquing the excesses of the progressive Left. In 2019, the former president made headlines for noting “a sense among certain young people on social media that the way of making change is to be as judgemental as possible about other people”, before telling them to cut it out.

“This idea of purity and you’re never compromised and you’re politically woke, and all that stuff — you should get over that quickly,” he said. “The world is messy. There are ambiguities. People who do really good stuff have flaws.”

In her final chapter, titled “Going High”, Michelle Obama echoes these sentiments: “We’ve become adept at making noise and congratulating each other for it, but sometimes we forget to do the work,” she writes. “With a three-second investment, you may be creating an impression, but you are not creating change.” The subtext is clear, if unflattering to today’s keyboard warriors: You’re not helping. Calm down. Grow up.

The former president has come in for a not-insignificant amount of criticism over comments like these, denounced by one writer as “yet another needless prescription of acquiescence to a bloc of Americans on the wrong side of history”. It’s a fair bet that his wife, with this book, will invite a similar backlash from people who believe that going high, especially amid the looming threat of another Trump presidency, is a fool’s errand. Some people will even go so far as to create a new projection, a new ghost-self to join the others: Republicans will point to the book’s discussion of race, gender, and obnoxious Fox News commentators as evidence that the former first lady is far woker than she cares to admit, even as progressives who feel called out by the book accuse her of being a crypto-conservative.

But if Michelle Obama believed in going high even amid the outrage and agita of Donald Trump’s first bid for the White House, surely she won’t allow the more radical elements of her own side to drag her down into the mire now.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe