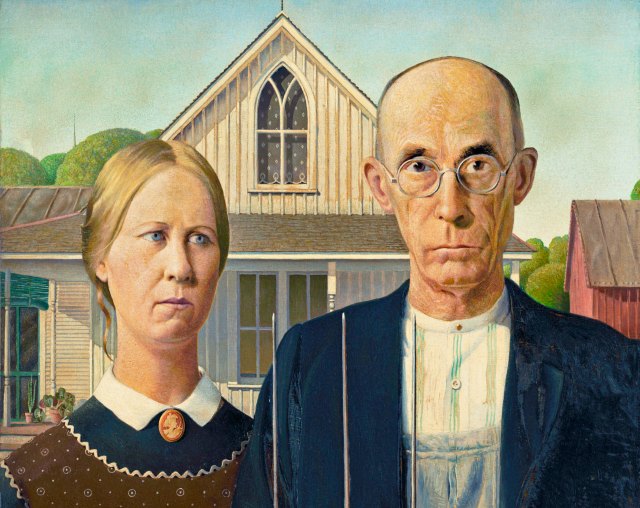

This is not a utopia (GraphicaArtis/Getty Images)

Christopher Lasch’s posthumous comeback began around the same time Donald Trump was elected. In the years since, his inter-connected critiques of contemporary humanity’s narcissism and our globalised elite have turned him into a prophet of the populist Right’s anti-elite politics. But this newfound popularity of Lasch, nearly 30 years after his death, obscured both problems with and hidden resources within his work.

In the 1990 reissue of The Culture of Narcissism, he called on Americans to rediscover the tradition of “populism”. Based on values of “competence”, “discipline” and “work ethic”, the populist tradition in America was associated with aspirations of economic self-sufficiency and social stability. It had often found expression in apparently backward-looking political movements aimed at protecting small farmers and artisans from the encroachments of industrial capitalism.

Lasch’s defence of populism, however, contradicted key aspects of his analysis of postwar American society. He recognised, for instance, that the vanishing worldview of Middle America was primarily an ideology by which elites of the 19th and early 20th centuries manipulated the masses. Instilling in ordinary people a love of work and aspirations to property ownership was not necessarily in their interests, but it did reflect the needs of the American economy at the time. By the mid-20th century, as the US transformed into a consumer society, elite ideology shifted towards an emphasis on “authenticity” and an obsession with self-image. Lasch understood this, but nevertheless insisted that the ideology of the “old order” would be indispensable in escaping the present. This amounted to the sort of “Ghost Dance” mode of resistance Kurt Vonnegut parodied in his early novel Cat’s Cradle — the elevation of nostalgic pieties into a political programme.

Lasch’s sympathy for populism also conflicted with his psychoanalytic perspective. He emphasised in The Culture of Narcissism that our capacity for rational collective action — that is, for decent politics — is being degraded by our increasingly thin and inward-looking sense of selfhood. We have withdrawn from associational life (political parties, unions, clubs, churches) and immersed ourselves in short-lived, increasingly virtual pseudo-relationships. And so we are less and less able to see the public sphere as an area for substantive debate and action toward common ends, rather than as a stage for narcissistic self-expression.

We are, in turn, enthralled by a new kind of elite who rule us through their celebrity. We have replaced the traditional patron-client structure of politics (we follow elites because they advance our material interests) with a kind of cheerleading (or simping) for figures who represent our “values” in a political theatre. Our populist politicians, from Donald Trump to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and their supporters exemplify this narcissistic new politics.

It is, in a sense, both too late and too soon for populism as Lasch envisioned it. Populism was the expression of an economic order that no longer exists. Nor can we revive or replace it until we have escaped our infatuation with the self. What we need, to escape this vicious cycle, is a politics that makes us capable of politics.

In 1984, Lasch wrote a sequel to The Culture of Narcissism, The Minimal Self, which remains relatively neglected. In it, Lasch explored this paradox. He points beyond the shallow populism with which he is sometimes identified, and towards a politics aimed at the restitution of our psychological integrity. Arguing that the division of the political field along a Left-Right axis was outmoded, he tried to replace it with a new typology organised around different approaches to what he called the “politics of the psyche”.

Lasch saw three camps in this emerging psychopolitical spectrum: the “party of the superego”, “the party of the ego”, and the “party of Narcissus”. The emblematic figure of the first was Philip Rieff, who, in The Triumph of the Therapeutic (1967), had articulated a powerful critique of our norm-less and atomised society. His 1973 follow-up Fellow Teachers, unjustly overlooked today, was a powerful defence of the Freudian superego — the part of the psyche that enforces personal moral responsibility and respect for the “inhibitions” that make culture possible. In a rather cruel mischaracterisation, Lasch portrayed Rieff as a cultural conservative whose morality was based on conformism and “fear”, rather than a properly individuated awareness of one’s obligation to help others.

The “party of the ego”, by contrast, sought to empower individuals to survive in a competitive, isolating society by bolstering their capacity for self-interested competition. The watchword of its adherents — mainly members of the psychoanalytic tradition of “ego psychology” that dominated the United States in the decades following the Second World War — was “adjustment”. This tradition can be seen as the predecessor of the therapeutic movements of today, aimed at helping patients avoid emotional dependence on others, anxiety over the future, guilt over the past, and other barriers to being dynamic, “well-adjusted” economic agents.

The trouble with this advice, as Lasch notes, is not so much that it is ineffective as that it reinforces the social dynamics that create our psychological problems in the first place. Whether framed in more feminine and pseudo-progressive terms as “self-care” or in more masculine and Social-Darwinian terms as “grindset”, the “party of the ego” invites us to become more of what we already are: self-absorbed competitors who imagine that we must overcome our last shreds of decency to achieve happiness.

Lasch had the most sympathy for what he called the “party of Narcissus”, which may seem ironic, given his critique of narcissism. This group emerged out of the New Left of the Sixties, and particularly its radical feminist and ecological strands. It saw the basic problem of contemporary psychology not as a deficit of moral authority or the vulnerability of the ego, but as the alienation of the self from others and the world, driven in large part by our reliance on technology.

This rhymed with Lasch’s own critique of the 20th century as an era in which the technological domination of nature was now redounding on humanity itself — which had become, in the hands of doctors, psychiatrists, marketers and bureaucrats, a manipulable object. Through the critique of technology — and what, in the jargon of that period, was sometimes called the “technostructure” of government by unelected experts — the party of Narcissus, like Lasch himself, expressed its hopes for a new, more humane form of society oriented towards harmony rather than progress.

It is perhaps on the political Right that such ideas are most forcefully expressed today. Lasch emphasised that his new typology superseded the political binary, but fantasies of simple agrarian living, unprocessed food, and escape from modern technology now strike many as “conservative”. But whether its politics are coded as “Left” or “Right”, Lasch warned that the “party of Narcissus” aims at an impossible ideal. Seduced by the image of a self free from the contradictions of post-modernity, it is drawn into a retrograde fantasy politics.

What we need, Lasch insisted in the conclusion to Minimal Self, is not a doubling down on outmoded moral strictures, nor the shoring up of our brittle, anxious egos — nor, for all its desirability, the pursuit of a self wholly integrated in a post-technological society at peace with nature. Rather, we need to develop the psychic strength to bear the tensions of post-modernity: the searing gap between what we desire and what we can accomplish at present. The kind of person capable of political action in this environment is someone who can endure, without illusion, the growing desert — and looks beyond superannuated political identities for friends with whom he might find a way out.

The education of such individuals was in fact Rieff’s own project, as articulated in Fellow Teachers. It remains the task of some critical theorists on the Left, such as Benjamin Fong, who calls in his Death and Mastery (2016) for a pedagogical “politics that makes politics possible”. If we look past the dead-end of populism, we can see the road Lasch did not follow after Minimal Self — the search for a new kind of meta-politics aimed at the restoration of the psychological resources necessary for normal life. That search, one presumes, will bring us into company with strange fellow travellers and teachers.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe