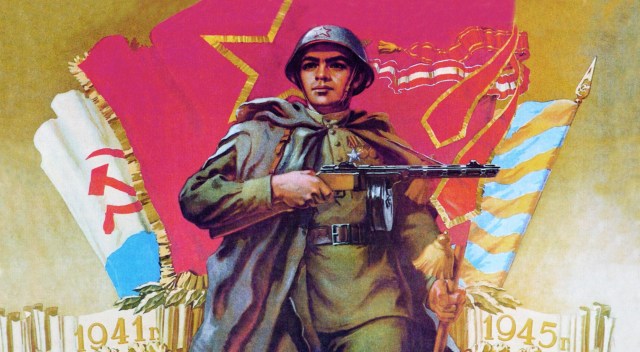

What would William Morris say? (Buyenlarge/Getty Images)

It is a strange time to be a socialist. When I was young, in the 2000s, socialism was about overthrowing capitalism or at least making it more fair for the workers condemned to toil within its structures. Socialism was unfashionable. Under New Labour, with its apparently pragmatic “third way”, socialism was treated as archaic and socialists as gauche and weird. For the socially ambitious, a commitment to the Left offered few opportunities. The institutional infrastructure was limited: it comprised an insignificant political party (Respect), the Morning Star newspaper, a single militant trade union (the RMT), and a handful of Trotskyist sects.

Now, though, that’s all changed. Since the financial crash of 2008 and the ascendancy of Jeremy Corbyn and Bernie Sanders, socialism has gone mainstream. The values the Left defends, primarily liberal and cosmopolitan, are almost a prerequisite for a career within the professions. It is unfashionable, or unseemly even, to reject them. But: this “socialism” is not what it once was. It is customary to locate the Left’s evacuation of class politics with the rise of the New Left in the Sixties, in particular, with the theory of the Frankfurt School philosopher, Herbert Marcuse. But the Left’s shift from economics to culture, however, was more protracted than this narrative suggests. It began in the Sixties and continued apace under neoliberalism in the Eighties and Nineties, as deindustrialisation undermined organised labour. Its denouement, though, was in the 2010s, after official communism had collapsed and social democracy had capitulated to the global market.

Responding to the comedian Russell Brand’s notorious Newsnight interview with Jeremy Paxman in 2013 (in which Brand defended socialism and attacked the vacuity of capitalist democracy), the cultural theorist Mark Fisher diagnosed the pathologies of the modern Left with precision. Even then, he captured its obsession with identity — above all, race, sex, and gender — its po-faced moralism, its joylessness, its resentment-fuelled feuding, and its individual competitiveness. In short, its unambiguously bourgeois subjectivity. Instead of celebrating Brand’s assault on the neoliberal status quo, the Left, nourished mainly by a poststructuralist diet of Michel Foucault and Judith Butler, responded by lambasting him as a fraud and a misogynist. With this it was clear to Fisher that the gentrification of the Left was complete. “The Left”, he wrote, “has all but disappeared”.

Not surprisingly, alongside the New-New Left’s elision of class is an ignorance, also, about its traditions. Proletarian literature — such as Robert Tressell’s The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole, and Alan Sillitoe’s novella, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner — is no longer a source of inspiration. (Presumably, too white and too male.) Nor are the figures who galvanised the first generation of Labour MPs into action: Thomas Carlyle, John Ruskin, Giuseppe Mazzini — and particularly William Morris. On the contrary, they are seen — if, that is, they are known about in the first place — as an embarrassment. Relics of the 19th century, nostalgic and reactionary, espousing superannuated opinions about the compatibility of nationalism and internationalism, capitalism as an unmitigated disaster, duty, and the dignity of labour.

The current Left isn’t interested in universalism, virtue, non-elective communities, or technical skill. It is relativist, individualistic, hedonistic, and preoccupied with abolishing borders and work. As one influential text put in 2015: “the classic social democratic demand for full employment should be replaced with the future-oriented demand for full unemployment”. It would be misleading to present the Left as a monolithic block. Both the socialists who wrote this (Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams), and their Fully Automated Luxury Communist successors, cared and care about class. But it is a version of class from which the traditional working class has largely been expunged, disciplined for bad behaviour — Brexit and various Brandish misdemeanours.

Nonetheless, the modernism these socialists embrace makes Marx seem parochial. The modern Left, if it is not totally blind to class, is excessively technophilic. It holds that because communism is dependent on a fully automated economy, it was impossible until now. The irony, however, is that the pseudo-socialism of the present moment — all narcissism and technocratic utopia — has been articulated and critiqued before. The revival of these ideas rhymes with a similar intellectual tendency which emerged in the 1880s. Then, the Left and the early Labour Party correctly rebutted it, sowing the ideational seedbed for our postwar welfare state in the process. But, if we are not careful today, this distorted socialism which has reappeared may win out, fundamentally corrupting any socialism rooted in class solidarity and egalitarianism.

Aside from the systematisation of Marx’s thought accomplished by Friedrich Engels during the period, three thinkers defined this debate on the Left in late-19th century: Edward Bellamy, the author of Looking Backward, the political Oscar Wilde found in his essay “The Soul of Man under Socialism”, and William Morris. The Left today is heir to the first two, and indifferent to, or unaware of, the third. Fully automated luxury communism is simply a rehash of Bellamy’s utopian novel. And its partner in crime, millennial socialism — a vague tendency rather than an organised phenomenon — is the unconscious offspring of Wilde, minus the wit, the self-conscious cynicism, and the theatricality. It was William Morris, on the other hand, who was to supersede the jejune arguments of both contemporaries.

Published in 1888, Looking Backward is set in the year 2000. Capitalism has evolved into communism. The state has nationalised the means of production, co-opted the efficiencies effected by monopoly capitalism, and rolled out labour-saving machinery wherever it can. People start work at 21 and finish at 45, with the option to opt out at 33 and receive some kind of Universal Basic Income. And while Morris would write his own medievalist utopia, News from Nowhere, in response, he also criticised Bellamy directly in a review in the socialist journal Commonweal. Looking Backward was a utilitarian travesty, he wrote, devoid of spirituality and offering no meaning or pleasure in life to its citizens. It was the thought experiment of a person perfectly satisfied with modern civilisation, the utopia of the professional middle classes concerned with order and the eradication of inconsistencies and waste. A “machine-life is the best Mr Bellamy can imagine”, Morris complained.

Unlike Bellamy, Morris believed that labour was a chief ingredient of a fulfilling life. It should not be dispensed with, but made pleasurable instead. Hatred of modern civilisation, with its severing of the connection between labour and art, was the “leading passion” of Morris’ life. What, he asked, will the workers make of Bellamy’s regimented scheme? They will reject it, naturally, as arid and dull. It was propaganda for capitalism. And the same is true of the soul-destroying machine lives concocted by post-work socialists today.

Who, after all, wants to be condemned to onerous leisure (luxury communists have presumably never been unemployed and, one imagines, count few retirees among them) and the rule of technical elites? Because that’s what the post-work socialists, scornful of work and workers, are devising for us in their books, journals, and think tanks. Even journalism and complex surgery will be delegated to machines. Instead, Morris believed that variety is enriching. Individuality is a social good. He also believed, however, in cooperation. The individual, as such, is a fiction and incapable of living well when it does succeed in breaking free of the group.

Oscar Wilde, by contrast, held that socialism was of value “simply because it will lead to individualism”. It relieved us of “that sordid necessity of living for others”. And more fully than any other 19th-socialist, Wilde was the herald of the concept of self-realisation, an idea that millennial socialists — eschewing customs, authority, and limits of various kinds — have adopted wholesale from Wilde’s foundations. “Be thyself,” he proclaimed, will be the motto of the new world. The difference is that, in his own time, Wilde remained an outlier; in ours these ideas are hegemonic on the Left.

As with many millennial socialists now, Wilde was unimpressed by ordinary people. Real people are people who have realised themselves. They are the poets, the philosophers, the scientists, the people of culture — in a word, they are the bourgeoisie. Betraying an extraordinary lack of imagination, Wilde saw the lives of the poor as containing no intrinsic value. They are spoilt by the performance of duties, where the self is sacrificed to others. “To live is the rarest thing in the world,” he wrote condescendingly. “Most people exist, that is all”.

In Britain, the Labour Party of the early-20th century chose Morris’s fraternal universalism over Bellamy and Wilde. Second International socialism in Europe likewise remained, for the most part, socially conservative. Almost across the board, until the Sixties, solidarity continued to trump subjectivity. Ignoring Wilde’s juvenile edicts, figures such as R. H. Tawney, Clement Attlee, and William Beveridge volunteered at charitable institutions like Toynbee Hall. They worked closely with the poor and the working classes, and, consequently, understood their trials and sensibilities. And they won elections too.

Before they can do so again, socialists must degentrify. And they can learn how from Morris. As he wrote of his imagined future in News from Nowhere, “this is not an age of inventions”. Now ought not to be either — either in technology or theory. Modern socialists, at any rate, are only reinventing the wheel.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe