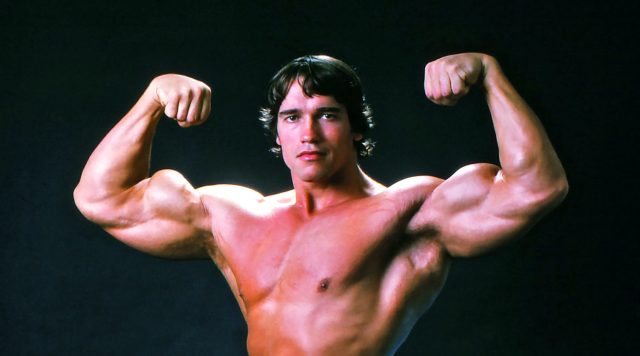

Who wants to look like a brown condom stuffed with walnuts anyway? Credit: Jack Mitchell/Getty Images

A spectre is haunting the gyms of the West. If the bodies on display there look better than they did in the Nineties or Noughties, the reasons go far beyond our expanded knowledge about training and nutrition. It’s thanks to steroids.

The Times last week reported that steroid use in the UK has increased tenfold over the past decade, while recent studies have shown that 2% of Canadians, and between three and four million Americans, have used steroids in their lifetimes — with roughly a quarter of those users reporting “psychological dependence” on the otherwise-non addictive drugs.

I have been on the periphery of the strength and fitness culture for my entire adult life, and steroids have always been part of the athletic game: if you want to win, not just at bodybuilding and powerlifting but at any sport, you take performance-enhancing drugs. Initially, I had primarily positive views about the drugs: steroids, I thought, were merely a means to an end, a way of getting stronger and increasing functional capacity, something reams of academic and anecdotal research have confirmed they do. However, I gradually learned that the individuals using them in this way are few and far between.

That small pool of people largely consists of pro athletes, driven by financial incentives or competitive instincts to pursue every conceivable advantage. But recreational users have always outnumbered professional users, whose livelihoods depend on athletic performance. And that gap has only widened as these drugs have become available everywhere from internet forums to legally operating testosterone clinics. Their pull is irresistible: a relative of mine who never played sports or even took to the bodybuilding stage was arrested for felony possession of steroids in 2014.

These recreational users are trying to win a different kind of game. When I started investigating steroids, an increasing number of users were following in the footsteps of Aziz “Zyzz” Shavershian, a Russian-born Australian who built a following on YouTube at the end of the Noughties. One of the first notable influencers to emerge on the now ubiquitous site, Zyzz preached a gospel of “aesthetics”, relying on steroids consumed in conjunction with exercise to develop a physique similar enough to his idol Frank Zane’s that it would win him the undying admiration of his followers.

The key difference, of course, was that Frank Zane — whom I interviewed a year ago — was a professional athlete, training his body to win bodybuilding pageants, and Zyzz was merely someone who wanted to look the part. Zane detested selfies and self-recorded footage, believing it to be deceptive and no substitute for up-close, objective inspection of another person’s body; Zyzz relied on these methods to project a particular self-image. Taking steroids arguably made him weaker and sicker, not stronger. Zyzz died after a cardiac arrest aged 22, the victim of a congenital heart defect and cardiomegaly — an enlarged heart — worsened by the drug use that, like many fitness influencers including the recently disgraced Brian “Liver King” Johnson, he had spent the majority of his career denying he used. (Zyzz’s deception was exposed a month before his fatal heart attack, when his brother Said was arrested for possession of anabolic steroids.)

Zyzz’s early death should have made him a cautionary tale. Instead, he became a “muscle martyr” beloved by other fitness posters. People like my felonious relative saw him and wanted to be him, while emerging social media platforms provided convenient playgrounds for their carefully-curated exercises in brand-building narcissism. I’ve now interviewed hundreds of users, and the reasons for their use all arise out of some sense of absence, some internal emptiness. A gay user whose steroid-abetted transformation I profiled explained to me that he wanted to transition from being a chubby, schlubby teen to a “hyper-masculine” man. Others said they added mass in the hope of “becoming someone”; all that hypertrophied flesh would obscure an essential lack of self. Several steroid users who were attending bodybuilding pageants merely as spectators told me how eager they were to be mistaken for competitors, that passing for one would constitute the highlight of their year.

“The first casualty of steroid use is the truth,” the fitness journalist and bodybuilding competition coach Anthony Roberts has told me repeatedly. Even if steroids are obtained with a perfectly valid prescription, there is still a cultural taboo that prevents most users from admitting to using them. As Roberts tells it, lying is the oldest and most effective performance enhancer of all: lying about what you take, how much you take, what else you take — because steroid use, for many, is but a small part of a drug-filled lifestyle. Certain fitness influencers, in addition to denying or at least staying silent about steroid use, have gone even further, inflating their on-screen workouts with the use of fake weight plates and exaggerated claims about their performance.

Meanwhile, they are risking their health. Heavy steroid users are already uniquely susceptible to cardiovascular problems — and so many influencers are using steroids in excess of what a physician would prescribe for therapeutic use. Those with pre-existing heart problems, like Zyzz, are uniquely vulnerable, particularly in recent times. During the pandemic, each widely-publicised bodybuilder death was met with waves of accusation: at first, it was the evil virus that did them in, then it was the “clot shot”. Never mind that most of these so-called “recreational users” are teetering on death’s doorstep at all times, aware that even a common cold could stop their engorged hearts.

Bodybuilding prodigy Dallas McCarver, for example, died in 2017 with organs so enlarged that they strained credulity, and a recorded testosterone level of 55,000 nanograms per deciliter (the normal range for a male falls between 300 and 1,000 ng/dl, and the highest recorded testosterone level captured in a failed Olympic drug test was 20,000 ng/dl). So, as they near peak muscularity, and fame, these bodybuilders are also nearing the end of their lives. Their spectacular bodies serve as both temple and tomb.

Hours of conversations with men like these have led me to believe that their behaviour is, in part, a response to the socioeconomic situation in which we find ourselves. Since the early Eighties, in the West, deindustrialisation has proceeded apace and the world of finance has become dominant. To people coming of age, it might appear as if nothing is made anymore but money. Farmers and manual labourers, such as the steamfitter captured in Lewis Hine’s famous 1921 photograph, sometimes exhibit a high degree of muscular development related to their jobs. By contrast, middle-class workers, performing increasingly less strenuous work for more than a century, have to actively cultivate muscular physiques to project power for which there might be little purpose — beyond showing that they aren’t subject to the degenerating tendencies of their age. In the absence of any tangible construction projects, the only thing that you can gain approval for building is your body — a body that is both an “aesthetic” calling card and a prison for your enlarging viscera and solipsistic thoughts.

In more recent years, there has been much commentary on declining male testosterone levels. Blame is assigned to everything from poisoned food to sedentary lifestyles. Some pundits, such as manosphere influencer Mike Cernovich, have urged men to set aside $80-100 a month for testosterone replacement therapy. Whereas Cernovich’s cohorts would most probably deride the prescription of SSRIs for depression, or oestrogen for transgender-identifying individuals, they accept a pharmaceutical solution for the crisis of masculinity. At least testosterone administered in a clinic is accompanied by regular blood tests that can detect cholesterol issues and other problems before they become dangerous. But it is still another of modernity’s many panaceas: here is a weekly or biweekly needle to the thigh or buttocks that will make you feel and perhaps even look like someone you are not, but feel entitled to be — or at least appear to be, on social media.

The overdiagnosis of SSRIs, the superfluity of steroids, and the legions of men killing themselves to look strong are tragedies. They are disordered responses to a kind of existential emptiness, a world in which our identities are all we have left to display and sell. And we know, deep down in our hearts, that such a meretricious product is worth nothing at all.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe