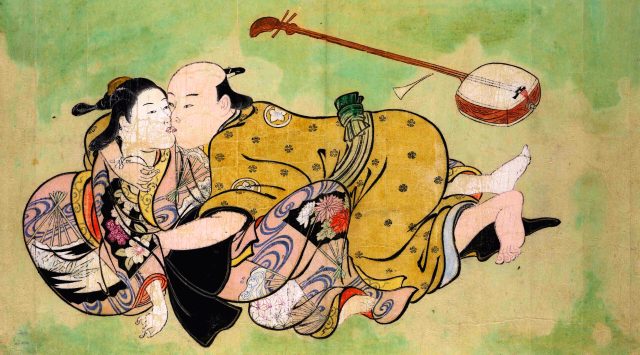

A man and geisha, ca 1714. Found in the Collection of British Museum. (Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

“Sex is where the weirdness of the Japanese peaks,” wrote A.A. Gill in his notorious “Mad in Japan” essay. Gill went on to catalogue largely anecdotal evidence of what he saw, on his brief visit, as a warped obsession with sex and a culture hard-wired to objectify and infantilise women who were, he asserted, seen simply as handmaidens or sex toys. Such characterisations, once typical, would now generally be dismissed as Japanophobic tropes — but occasionally a story will come along that seems to add fire to Gill’s wisps of smoke.

The Japanese government is considering raising the age of consent from 13 to 16 as part of a package of sex crime reforms. Yes, you read that right, the age of consent in Japan is currently 13, one of the lowest in the world and the lowest in the G7. A justice ministry panel is also recommending redefining rape to make court judgements more consistent. As it stands, it must be proved that not only was sex non-consensual, but that the victim had been unable to resist due to “violence or intimidation”. The new law will allow courts to consider drugging, intoxication, “catching the victim off-guard” and psychological manipulation in their definition. Voyeurism will also be outlawed.

That Japan is only now updating its laws is troubling, as it suggests a society indifferent to the fate of vulnerable minors and sexual assault victims. Just last week, a former J-pop star Kauan Okamoto claimed to have been sexually abused by the now-deceased music producer Johnny Kitagawa when he was 15. He thinks many more boys who worked for Kitagawa were also abused, but were afraid that speaking out would ruin their fledgling pop careers. “I believe that almost all of the boys who went to stay at Johnny’s place were victims,” he told reporters . “I would say 100 to 200 boys stayed there on a rotation basis during my four years at the agency.”

All this appears to add substance to the implications of the “weird Japan” reportage that fixates on the seedy elements of Japanese culture, such as the popularity of disturbingly young girl bands who cavort scantily clad in glossy videos. (Some members of the J-pop band NMB48 are just 14.) But as ever with Japan, things are not what they seem. The salacious Orientalist myth needs to be separated from the more prosaic reality. For one thing, it’s not exactly true to say the age of consent in Japan is 13. Most prefectures (or counties) interpret laws against “lewd acts” to include sex with minors. This means the real age of consent in much of the country is 18 — though penalties for “lewd acts” are generally lighter.

Still, that hardly explains why Japan’s sex crime laws haven’t been updated since the late Meiji period. The answer may lie in Japan’s traditional “black box” attitude to sexual crime. In a culture where direct expressions of opinion or intent are considered impolite and injurious to societal harmony, and everything is caveated or left unsaid, it is often considered too difficult to determine what happens in the “black box” of an intimate encounter between two individuals. The police and judiciary would rather not be asked to get involved — and nebulous sex crime laws that deter victims from coming forward have long suited them. Of course, it also benefitted predatory men.

Then there is the fact that the public was, until recently, largely unaware of the flaws of the outdated laws. Japan has a low official rate of sex crime at 1.02 per 100,000 citizens (the UK’s figure is 27), and horrific stories of abuse do not appear on the news. Nor does sexual abuse ever feature as a storyline in TV dramas. In the absence of compelling evidence of a problem, the dusty old ordinance remained on the statute books as there simply wasn’t any clamour for change.

That is, until recently. Japan is at its most dynamic and progressive when it feels the world’s gaze upon it, a phenomenon known as gaiatsu (“outside pressure”). Not all Western-inspired protest movements translate to Japan (BLM flopped), but MeToo took off in 2017. The behaviour of celebrities came under intense focus, with particular attention paid to how “talents” interacted with their very young fans. In 2017 the bassist of the band Tokio quit after forcing a kiss on a high-school girl, and actor Keisuke Koide had his contracts for TV dramas cancelled when it was revealed he had slept with a 17-year-old. Then, in the run-up to the Tokyo Olympics, Yoshiro Mori, a former prime minister, was forced to step down after implying that women talked too much in meetings. The director of the opening ceremony was sacked for likening the female star to a pig.

At the heart of Japan’s MeToo movement was Shiori Itō, a journalist and filmmaker whose rape allegations against a high-profile colleague saw her awarded substantial damages in 2019. Her memoir Black Box, published in 2017, became a bestseller, and she has since campaigned to change Japan’s century-old rape laws.

Ito’s story raised many awkward questions in Japan. Those impressively low crime statistics came under scrutiny: a government survey in 2019 found that only 14% of victims of sexual assault had reported the crime. And the survey only questioned those aged 16 and above. The reasons given were a lack of faith in the police, a belief that their trauma was unimportant, and shame. In a country where stoic endurance is prized and maintaining societal harmony is considered of far greater value than personal suffering, underreporting is a serious issue.

However, there is a limit to Japan’s tolerance. In 2019, a series of technical acquittals in four sex abuse cases involving minors sparked outrage. This included a horrific case in Nagoya, where a man was acquitted despite the judge acknowledging he had repeatedly raped his teenage daughter and had threatened to beat her if she refused. The judgement hinged on whether the young woman could have resisted: the judge ruled she could have done. A higher court overruled the judgement, and the man was given a 10-year sentence, but the dangers of the ossified penal code had been exposed and calls for changes to the law intensified.

Gaiatsu may be a factor in the timing of the proposed changes. Japan will host the G7 summit in Hiroshima in May and Prime Minister Fumio Kishida — who was schooled in the US and is on a mission to harmonise Japanese society with Western norms — will not want any embarrassment spoiling his showpiece.

Kishida has already made efforts to rid Japan, which is ranked 116 out of 146 in the gender gap index, of its chauvinist reputation. Last June’s Intensive Policy for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women required firms to disclose their gender pay gaps; last December, Japan hosted the sixth World Assembly for Women, featuring luminaries such as Malala Yousafzai and Christine Lagarde. Kishida is likely to welcome the justice ministry’s sex crime reforms and push through the necessary legislation swiftly.

This is all well and good, except that the proposals appear to be more about sanitising Japan’s international image than protecting vulnerable young people. The bar for rape conviction will remain high: Human Rights Now have said it will still fail to meet international standards. Whether the new policy will cut through on the international stage is also in doubt. Two weeks ago, thousands of tourists flocked to Kawasaki to attend its annual Penis Festival — much to the mirth of the Western press. But what foreigners often don’t realise is that the defining aspect of Japanese sex culture isn’t, as A.A. Gill claimed, its weirdness — but its secrecy.