The most important element in the debate over the utility of Western sanctions against Russia, is also the most ignored. The sanctions regime mostly comprises of restrictions that have been deployed before, such as export bans and the freezing of certain assets. Even the controversial exclusion of a number of Russian banks from the main international banking message system, SWIFT, was not exceptional, having already been used against Iran.

But the freezing of Russia’s foreign-exchange reserves, worth around $300 billion — about half of its overall reserves — was significant. While the US had behaved similarly with Afghanistan, Iran, Syria and Venezuela, none of these targets was remotely as powerful as Russia: a member of the G20, and the world’s largest nuclear power. Likewise, none of the 63 central banks that are members of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in Basel — known as the central bank of central banks — had ever been the target of financial sanctions, not even during the Second World War.

At the time, the decision received relatively little attention. Future historians, however, will look back on it as the trigger that set in motion one of the biggest snowball effects in history, one which now threatens the very foundations of the American Empire.

In our age of fiat money, reserves aren’t held in the form of physical dollars (or other currencies) stashed in the vaults of foreign central banks. They are simple IOUs — a credit recorded in the accounting sheets of the Federal Reserve and other central banks. In the dealings between countries, just as in the dealings between individuals or companies and commercial banks, trust is therefore fundamental: just as you would never deposit your salary in a bank if you had even the remotest fear that it might freeze or confiscate your money, no country wants to hold reserves which may be snatched away at any moment.

This move, therefore, violated an almost sacred principle: the neutrality of international reserves. The message was clear: from now on, the US would stop at nothing to punish countries that stepped out of line or defied Western diktats. And if this could happen to Russia, a major power whose central bank reserves were mostly earnings from sales to the West, it could happen to anyone. As Wolfgang Münchau wrote, by weaponising international reserves, the US had “taken the biggest gamble in the history of economic warfare”. In one fell swoop, he noted, the US had “undermined trust in the US dollar as the world’s main reserve currency”, and encouraged China and Russia to “bypass the Western financial infrastructure”. For non-Western nations — especially China, which is heavily exposed to US assets — disengaging from the dollar, and more in general from the US-led international monetary and financial system, acquired a sudden urgency.

De-dollarisation was not something that would happen overnight, that much was clear. But the wheels of history were set in motion. It is no coincidence that most of the world’s nations didn’t join the West in slapping sanctions on Russia, but quietly started strengthening their ties with Russia and China in an effort to reduce their dependence on the dollar-centric system. In just over 12 months, the world has undergone a greater tectonic shift, in geopolitical terms, than it has in decades: the long-heralded post-Western international order — comprising the BRICS and dozens of other countries making up most of the world’s population — has finally become a reality. The US, as former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers recently said, is lonelier than it has ever been.

A key driver of this process has been the world’s gradual disengagement from the dollar. Its demise has been endlessly — and wrongly — predicted since the Sixties, so scepticism here is justified. This time, however, there is good reason to believe that it’s happening. De-dollarisation comes in many forms, but three are particularly easy to spot: the settling of international transactions in currencies other than the dollar, primarily the Chinese yuan; the reduction of the dollar in global foreign-exchange reserves; and the decline in foreign holdings of US Treasury bonds.

On all counts, the trend seems clear. In terms of international payments, the role of the yuan (and other currencies) has received a massive boost over the past year. The most obvious example is Russia, which has effectively been forced by the Western sanctions to embrace the yuan for most of its international transactions. But several other major countries — including Brazil, Argentina, Pakistan and Bangladesh — have already agreed to (or are in the process of negotiating) the use of the yuan or their own currencies to settle their international transactions. Meanwhile, the BRICS are also working on developing an international currency along the lines of the synthetic alternative proposed by Keynes 70 years ago, the bancor, which was rejected by the Americans in favour of a system anchored around their dollar.

Beyond the BRICS, interest in de-dollarising — or at least in greater use of local currencies — is also growing, most notably in the Persian Gulf, where the US previously wielded unrivalled strategic power. At the first China-Gulf Arab States Cooperation Council summit in December reached a consensus to use yuan for oil and gas trade. And last month, China and the UAE conducted their first transaction in yuan.

Looking at the composition of global currency reserves, the shift towards de-dollarisation might be less apparent. But it is happening. The nothing-to-see-here crowd might point out that the US dollar still dominates the world’s currency reserves, with around 60% of the total, while the yuan accounts for less than 3%. But static snapshots of the present, though true, are of little use in understanding what the future holds. And, according to current trends, the dollar’s share of reserve currencies has begun to contract at 10 times the average speed of the past two decades. Central banks are mostly dumping dollars for gold, while overseas creditors — China, Japan and Saudi Arabia in particular — are increasingly selling off US Treasury bonds.

Such is the progress of de-dollarisation that many in the Western policy establishment are starting to acknowledge that this time is different. Last week, for instance, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen admitted that the weaponisation of the dollar through the use of financial sanctions risked undermining its hegemony by pushing countries to look for an alternative, even if its supremacy wasn’t at risk soon. Just two days later, Christine Lagarde, the President of the ECB, made a similar statement, acknowledging that there was now “an opportunity for certain countries seeking to reduce their dependence on Western payment systems and currency frameworks”. She stressed that these changes do not amount to an “imminent loss of dominance for the US dollar or the euro”, but they do “suggest that international currency status should no longer be taken for granted”. The question, then, is no longer if de-dollarisation is happening — but how fast.

Sceptics, however, continue to argue that there are insurmountable technical and institutional obstacles to the dollar’s decline. They point out, for instance, that there are economies of scale that lead to a relative monopoly in reserve currency status, and that the Chinese yuan cannot become a real reserve currency unless capital controls are phased out and the exchange rate made more flexible. Moreover, they claim, a reserve currency country needs to accept — as the US has — permanent current account deficits in order to satisfy the world’s demand for its currency.

Therefore, there would need to be major changes in China’s financial markets and monetary-economic policies for the yuan to replace the dollar. These are valid claims, but they miss a fundamental point: the de-dollarisation process is primarily geopolitical in nature, not economic. It’s not just about finding an “efficient” system, but about challenging Western monetary hegemony. Moreover, de-dollarisation doesn’t necessarily mean the replacement of the dollar with the yuan, but the dispersion of reserve assets among several major currencies, and other assets, such as commodities such as gold.

And this would be no bad thing. The world’s reliance on the dollar makes economies excessively exposed to changes in US monetary policy, with periods of monetary loosening or, as now, tightening having dramatic knock-on effects on the rest of the world. Nor would this completely be to America’s disadvantage. As Michael Pettis and Matthew Klein argue, the current international and monetary financial system doesn’t pit the interests of nations against each other so much as it pits the interests of certain economic sectors against other economic sectors. In other words, it is not the US as a whole that benefits from the global dominance of the dollar, but rather certain constituencies within the US.

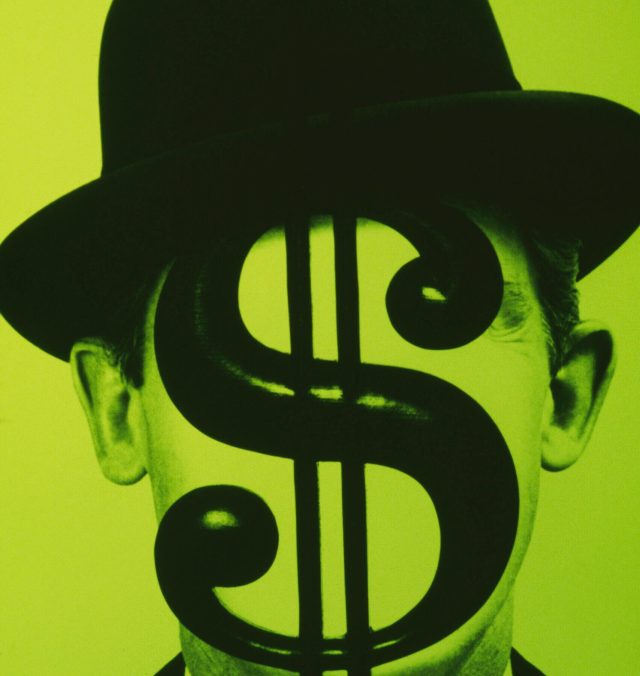

By attracting capital to the US and allowing it to help itself to foreign goods and resources such as oil, simply by printing its own currency — in what Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, de Gaulle’s Minister of Economy, called America’s “exorbitant privilege” — dollar dominance has undoubtedly benefited America’s imperial elites: Wall Street, large global corporations and, most importantly, the national security establishment. It’s what has allowed the US to sustain a regime of perpetual war, on top of exercising financial dominance over much of the world.

But this has come at a significant cost not only for the rest of the world but also for American workers, farmers, producers and small businesses. For America, supporting the world’s primary reserve currency has meant running permanent trade deficits, which has seriously eroded its industrial and manufacturing capacity and its ability to provide well-paying jobs to its workforce — what Pettis calls the “exorbitant burden” of the dollar. The end of this supremacy, then, would turn America into a somewhat “normal” country — a regional power among other regional powers. Both globally and within the US, this would benefit virtually everyone. Indeed, the only losers would be those who have had ample time to enrich themselves.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe