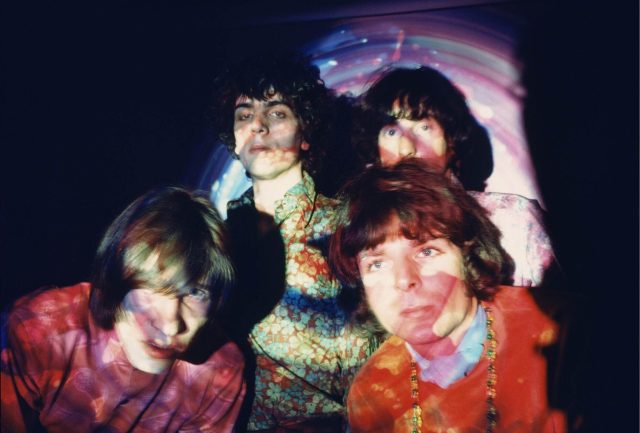

Syd Barrett (top left) with Pink Floyd (Andrew Whittuck/Redferns)

Bankruptcy is not the only thing that proceeds gradually, and then suddenly. While Syd Barrett may have appeared fine in an interview in May 1967, his teetering mental state would change drastically by the summer. Locking himself in his bedroom for days, the formerly placid frontman of Pink Floyd became crudely violent, on one occasion smashing a mandolin over a girlfriend’s head. “This angelic boy became this… moody, impossible to work with, violent man,” said his friend David Gale. Initially, Barrett’s antics were exoticised as the floridities of a ‘mad artist’. While testimonies vary, many blamed, at least in part, his excessive use of LSD.

Barrett is the main case study of the “acid casualty”: the archetypal subject who, after a few too many trips, is said to endure a mental collapse from which they may never return. His story is frequently shared as a parable in online forums such as Reddit, which is a recruitment pool for psychedelic studies. And while attitudes around psychedelics have softened in recent years, this meme still lurks subtly within the public consciousness. One doesn’t have to ask too many baby boomers before someone shares a story, perhaps of a friend from school or university, who got lost ashore on the other side.

The first recorded reference I could find was in 1974, from Changes magazine. A passage spurns the “unique contemporary type: that kind of burnt-out acid casualty who ends every sentence with ‘Man’”. Amid the Nixonian disappointments of the Seventies, the acid casualty was a way to culturally dismiss the psychedelic ruptures of the Sixties. No longer an agent for spiritual awakening or a wonder treatment, LSD was cast as a trigger for madness and a tool for mind control. Many casualties were reported in the press: Peter Green of Fleetwood Mac, Roky Erickson of the 13th Floor Elevators, Arthur Lee of Love, and Brian Wilson of The Beach Boys, who suggests his LSD experiments “fucked with his brain”.

What really caused these cases of psychosis is not known for certain, but the explanation usually focuses on their internal worlds. In a new film about his life, Have You Got It Yet?, some of Barrett’s contemporaries cast him as an Icarus figure — one who communed with the Gods prematurely and “reached for the secret too soon”. Other narratives are less grand: perhaps he “boiled his brains with acid”, sustaining real organic damage to his nervous system through excessive chemical stimulation. Or perhaps the breakdown was inevitable. His former bandmate David Gilmour suggests that Barrett had in him a “switch waiting to be turned”, a “weakness of some sort”, maybe a vulnerability embedded in his genes. Such determinism echoes the public understanding of severe mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia.

However useful such layers of analysis can be, they risk downplaying the external factors that might have engendered the distress. If an individual takes a drug to cope with experiences they find hard to bear, it is not necessarily wise to blame the drug for any subsequent mental break. Touring several nights a week for months straight, Barrett’s deranged behaviours could be partly triggered by the exploitative atmosphere of the music industry.

“He feels that the application of commercial considerations is harmful to the music,” a report in Melody Maker stated in December 1967 — after the chart failure of “Apples and Oranges”, a by-the-numbers psych-pop single that Barrett had written amid intense managerial and label pressure to produce another hit. “He’d like to cut out the record company, wholesalers and retailers.” The same year, Pink Floyd performed on Top of the Pops for the first time, and Barrett expressed some reluctance to go on stage. It was then that Pink Floyd’s bassist Roger Waters first noticed that something might be wrong.

Barrett deteriorated rapidly. Before another scheduled performance on Top of the Pops, he turned up at a friend’s door barefoot and in a panic. In 1971, Barrett — now three years out of Pink Floyd — refused to leave his home for a photoshoot; he was afraid of “aliens”. What appears to be deranged at first makes a kind of sense when one considers that the aliens he feared were in fact his managers and hangers-on.

Robert Chapman’s biography describes how, even after Barrett had achieved some semblance of later-life balance in his hometown of Cambridge, obsessive fans would regularly knock on his door, film him with camcorders, steal his paintbrushes, climb over his fence, pose as couriers to secure autographs, and scan the neighbourhood trying to catch a glimpse. And something strangely under-discussed in the documentary and Barrett’s biographies is how the massive success of his former band — which had ejected him without warning in 1968 — might have made him feel. It can’t be a coincidence that Barrett retreated into isolation at the Chelsea Cloisters Hotel just as Pink Floyd hit the big time in 1973 with Dark Side of the Moon, which is partly about him and his madness.

Many acid casualties were as much victims of a music business that eviscerates its workers as of overwhelming psychedelic trips. Peter Green of Fleetwood Mac rejected the music industry in even more radical terms than Barrett, pledging to give away his earnings to charity, to reflect his new Christian beliefs; a move viewed by his contemporaries as the initial spark of his madness. The 13th Floor Elevators took LSD daily for long stretches of the Sixties; but their breakdowns were surely influenced by the predation of the local Texan police force, which sought to destroy the band’s acid evangelism through arrests and threats of violence.

Someone else deemed an acid casualty is Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones, the subject of a recent BBC documentary. On top of the relentless psychoactive effects of fame and public pressure, Jones’s paranoia can be seen a response to prohibitionist drug policies: after a humiliating court appearance for drug possession Jones, as Nick Kent writes, “was too scared to go into a shop to buy cigarettes even, because he thought anyone behind the counter had to be a plain-clothes cop”. Jerry Berkers, bassist of the Krautrock band Wallenstein, may have collapsed under the weight of his LSD visions, but it’s thought his trips reacquainted him with the trauma of time spent serving in Vietnam.

And yet, our interpretation of mental breaks often place little emphasis on the worlds in which they’re situated. In his classic text, The Triumph of the Therapeutic, Philip Rieff describes the ascendancy of the “Psychological Man” — the embodiment of late modernity — who understands himself in internal terms. We are our thoughts; our self stands behind the glass of our eyes, variously disappointed and enchanted with the stream of our inner lives flowing out into the world we perceive. And yet in studying history’s casualties, it seems that what was happening on the outside was flowing into, and warping, their internal worlds.

Even among those who reject the simplistic diagnosis of acid casualty, a more subtle form of othering can occur. “There can be no doubt that Syd was a schizophrenic,” Waters said — despite the fact that Syd was never diagnosed with anything other than an undisclosed personality disorder. Indeed, the schizophrenia diagnosis, applied to many of history’s casualties by both psychiatrists and onlookers, may seem like an objective description. But the reality is far more complex.

Schizophrenia is popularly understood as a biological phenomenon: an organic madness, in which its primary explanation lies within the individual. But poor outcomes for schizophrenia are independently shaped and predicted by parental socioeconomic status, poverty, class, immigration status, living in urban environments, and membership of a racial minority. Evidence tentatively suggests that those labelled schizophrenic in countries such as India and Ghana fare better than those in the United States, since they are less likely to be medicalised or face the stresses of developed modern life. This supports the idea that the music industry’s pressures may have been far more harmful to the acid casualties than either their original or psychedelically altered brain chemistry.

It’s easy to apply the labels of “acid casualty” and “schizophrenia” — and it sounds authoritative — but, in truth, the latter diagnosis is broad, vague, and variably administered. Dr Robin Murray, one of the UK’s most senior psychiatrists, suggested in 2017 that “the term schizophrenia will be confined to history, like ‘dropsy’”. As early as 1973, when many casualties were being diagnosed, the World Health Organization suggested that, for all its faults, the term should be preserved partly “for the benefit of non-professional contemporaries who enjoy talking about schizophrenia without knowing what it is”.

Commentators are therefore right to remark on the hypocrisies of “mental health awareness”: depression and anxiety are being unduly neutralised in the language of medicine, while “serious conditions like psychosis and schizophrenia are being overlooked”. The general public was understandably struck by the news last year that depression is not, as they’d been told, a mere “chemical imbalance”. The Moncrieff paper fast became one of the most accessed in modern history. But the popular reckoning with the parameters of schizophrenia is nowhere to be seen.

It is acknowledged even in the DSM-5, psychiatry’s “Bible”, that the majority of those who develop psychotic disorders have no family history of the disease — weakening the idea that genetic predisposition can fully explain mental breaks. The medical establishment has found hundreds of biomarkers “associated” with schizophrenia, but many of them overlap with other conditions, and may point to a broad “sensitivity” — which may make mental collapse more likely, but not inevitable.

But since the Sixties, the biogenetic model of schizophrenia has been in ascendance; and the basis of diagnosis always influences the rationale of treatment. Just as the understanding of depression as unsettled brain chemistry allowed some irresponsible medical practitioners to sell antidepressants as a silver bullet, our understanding of mental breaks as caused entirely by internal factors can be harmful. Many acid casualties faced great failures from the psychiatric sector following their diagnoses: involuntary electroshock, premature discharges, and shocking over-prescription.

None of this is to say that our treatment of those experiencing mental breaks has become worse since the Sixties. The antipsychotics on offer now seem to be more tolerable than those of their forebears. But stigmas towards psychosis and schizophrenia have, by some measures, deteriorated — possibly because of the othering that associates the stereotyped schizophrenic with some alien influence in their nervous system. Though we might not label anyone an acid casualty these days, our readiness to see mental distress as solely internal may prevent us from reckoning with the unhealthy pressures our society places on individuals. Psychiatry always attempts to remain apolitical. But it might do well to accept that mental breaks can, at least in part, be blamed on a troubled world in which, to quote psychiatric researcher John Read, “bad things happen and can drive you crazy”.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe