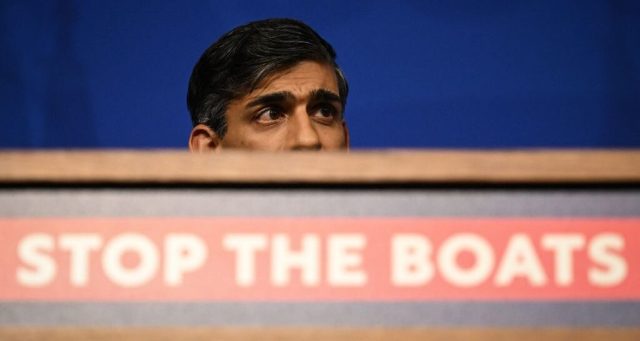

Can’t or won’t? (LEON NEAL/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

The Supreme Court’s ruling against the Government’s Rwanda plan may have been a foregone conclusion, but the broader political fall-out was not. Even though the Supreme Court struck down the migrant bill without relying on the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) or the Human Rights Act, the decision is nonetheless bound to reignite the discussion about the ECHR — which is what kickstarted the British courts’ judicial review of the bill in the first place.

For years, critics of the ECHR have argued that the Convention and its handmaiden, the European Court of Human Rights, represent an unacceptable infringement on national sovereignty. Supporters of the ECHR, on the other hand, claim that it has been an important driver of social progress, helping to redress blind spots within the UK’s legal system.

In a way, both sides are correct. Consider the ECHR’s most important UK-related rulings — ranging from homosexual equality to journalistic freedom — and few would disagree that it has played an important role in strengthening the protection of citizens’ rights in Britain. Yet it is also true that the ECHR raises important issues over sovereignty and democratic legitimacy. Should a supranational court have the right to decide whether a certain bill, approved by an elected parliament, passes the ethical and moral litmus test?

It is, though, a mistake to treat the ECHR in isolation, as its critics do. For the same question could be asked of any national court, including the Supreme Court itself. The influence of the ECHR is only one part of a much bigger story: the wider judicialisation of our political and democratic systems.

Over the past few decades, an unprecedented amount of power has been transferred from representative institutions to judiciaries, transforming national and supranational courts into full-blooded political and decision-making bodies — and giving rise to a new type of political regime altogether: what some have called juristocracy. As legal scholar Ran Hirschl wrote as far back as 2004, from matters of national security to macroeconomics, “courts have become crucial for dealing with the most fundamental questions a democratic polity can contemplate”. The view that “nothing falls beyond the purview of judicial review”, as Aharon Barak, the former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Israel, said, has become widely accepted.

As a result, it has become standard practice for core political decisions relating to the very essence of public life — such as immigration policy — to be taken by courts and judges. Questions that ought to be resolved through public deliberation in the political sphere are increasingly being settled behind closed doors by a self-selecting judiciary elite. Power has been delegated away from elected bodies and towards technocratic institutions — not just courts but also quasi-autonomous administrative bodies within the state, as well as supranational political-economic institutions such as the European Union. This process of judicialisation has disrupted the equilibrium between the various branches of government, and the fundamental principle of the separation of powers, transforming judiciaries into de facto legislators, at the expense of democratic deliberation.

In this sense, critics of the ECHR are right to claim it usurps the functions of democratic institutions, just as the EU does. As the former Supreme Court judge Jonathan Sumption recently made clear: “The [European Court of Human Rights] is now much more than a judicial body. It is a great factory for making law, which has become a legislative and political authority for the whole of Europe… It is political because many of the issues which it decides are matters of political judgement on which states can legitimately differ.”

But the Convention is only one facet of a much bigger problem: the juristocratic regime. And this is more than just a scholarly issue — it is a matter of class and power.

The birth of today’s juristocracy dates back to the late 19th century, when the gradual establishment of universal suffrage led to growing anxiety among ruling proprietarian elites, including most liberals including Mill, about the entry of the lower classes into government. The fear was that the extension of the franchise would disrupt social stability and constitutional principles — and, more precisely, that the working classes would use their new-found political rights to challenge the dominant economic order.

Most governments responded to this threat by effectively restraining popular participation through a mixture of parliamentary sovereignty, rule of law and formal or informal constitutional conventions. In England, this came to be known as the Westminster system, a regime premised on the idea that Parliament was the only body with the authority to make laws, thus implying the subordination of the judiciary to the legislative.

This form of political system became increasingly prevalent in Europe in the years after the First World War — and, in most cases, the power of the court to influence the legislative and political process was fairly limited. Indeed, as of 1942, only Norway had a constitutional court with the power to throw out laws adopted by the national legislature. Throughout the Forties and Fifties, however, several countries — including Germany, Italy, France and Austria — adopted constitutions that instituted courts with the power of judicial review: the power to examine, and eventually overturn, the decisions of the legislative and executive arms of government, if deemed in breach of the constitution.

This gave rise to the model of “constrained democracy” that was later emulated across most of Europe: one which possessed all the formal elements of democracy but where the ability of the masses to influence policy-making was subject to new sets of constraints. Though these constitutional courts were officially created as “guardians of the constitution”, they were in fact just as much guardians of the emerging US-led international order. Indeed, the early post-war years also saw the emergence of courts that were international or supranational in their own right, in Europe in particular, most notably the European Court of Justice and the European Court of Human Rights.

Westminster-style polities, such as the UK, were largely immune to this trend. But in the Seventies, the push towards judicialisation underwent a massive acceleration, including in the Anglosphere. Faced with growing pressure from an increasingly militant and politicised body politic, political elites resorted to various forms of depoliticisation — the removal of political decisions from the realm of popular-democratic contestation — in order to escape such pressures.

Judicialisation was one of the key tools — by either relying on the courts to challenge existing aspects of the social order that would have been hard to change through the normal channels of democracy, as Thatcher did, or by outright transferring power from majoritarian decision-making bodies, such as parliaments, to courts at the domestic and supranational level.

As Hirschl explained, even though this transfer of power might appear to run counter to the interests of political elites, in fact it served their interests very well. It allowed them to “scapegoat” the courts for policies they themselves wanted, safe in the knowledge that high judges tend to reflect the elite consensus on major cultural and political issues. “Deference to the judiciary, in other words, is derivative of political, not judicial, factors,” he wrote.

For the UK, this journey largely accelerated with its entry into the EU in 1972, which over time transformed EU law into something akin to a higher law. The second big push towards judicialisation came in the late Nineties and early 2000s under New Labour, with the creation of the Human Rights Act and then the Constitutional Reform Act of 2005, which paved the way to the creation of the Supreme Court in 2009.

Yet for Britain’s political elites, judicialisation still carried a risk — namely, that the courts would start producing judgments that no longer reflected the ideological preferences of those who handed authority over to the judiciary in the first place. Hence, the Conservative Party finds itself unable to enforce its Rwanda policy.

So, when leading Conservatives claim that the ECHR represents an infringement on democracy and parliamentary sovereignty, and that leaving the ECHR is necessary to complete the “Brexit project”, they are not wrong. The problem, rather, is that these arguments ring hollow.

After their victory in the EU referendum, many hoped that Britain’s democratic rejuvenation was just beginning; instead, the Conservatives have gone out of their way to avoid democratic scrutiny. They have a Prime Minister who rules without a democratic mandate, and a party machine which seems more interested in internal squabbles than fulfilling its electoral promises.

Should we be surprised, then, that a majority of people, according to a recent poll, don’t want to leave the ECHR? Perhaps they realise that, for withdrawal to make sense, it needs to be part of a radical project of re-democratisation. But that would require the existence of a political class that believes in democracy. Even if the Tories somehow manage to conjure up a way to bypass the Rwanda ruling, that uninspiring reality is unlikely to change.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe