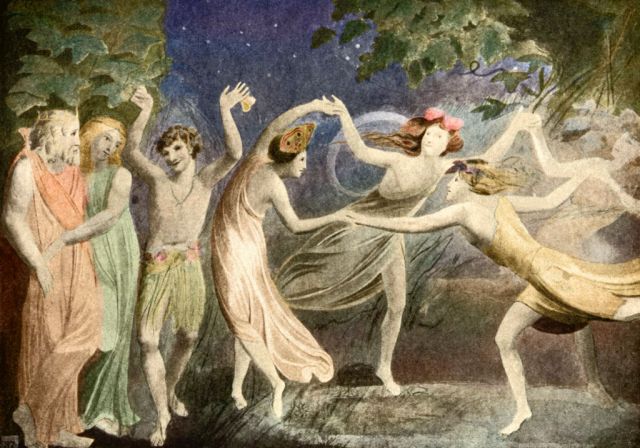

On a fairy hunt (Bridgeman/Getty)

It’s a long time since I took mushrooms, but my recollection is that the experience is profoundly reality-warping. Assumptions dissolve; mundane details or textures are suddenly fascinating; the wider world no longer echoes back your habitual understanding of it, but invites wild new interpretations.

Such an experience is starkly at odds with the world we inhabit today — one that has, over recent centuries, been progressively disenchanted by its subordination to the instrumental logic of science and technology. Medieval Christianity viewed the world as a book of signs, written by God and open to poetic or mystical interpretation. It was only around the 17th century — the age of Bacon and Descartes — that we began in earnest to lose the capacity for this kind of thinking. Then God first withdrew to the status of “watchmaker” for the world as mechanical watch, and finally — for many — disappeared altogether in favour of science and logic.

The shift away from the medieval mindset toward the scientific one is usually seen as a positive one. But it has left us poorly-equipped (unless we’re on mushrooms) to grasp just how different the thought-worlds of our forebears were, and how thronged with the uncanny. As folklorist Francis Young recounts, until relatively recently the British Isles was alive with “godlings”: spirits, creatures of legend and folklore. Young recounts the record of 6th-century Welsh St Samson of Dol, who reportedly encountered a terrifying “theomacha”, a “God fighter”, while travelling through a Welsh forest – an entity in the figure of an old woman who attacked and injured St Samson’s companion. Nor were such eldritch encounters only a feature of the so-called “Dark Ages” that preceded the medieval era. The 12th-century Gerald of Wales recounts meeting a man who would converse with “tiny huntsmen” who would tell him people’s secret sins.

Sometimes on woodland dog-walks after dark, the gleam of my torch will catch the eyes of a hidden muntjac and I’ll realise with a jolt that the woodland has been watching me all the time. When I try to picture life with all those non-human watchers, but without the comforting beam of light, it’s easy to imagine knowing that fairies are real.

At the very least, perhaps such beings represent a poetic way of expressing something indisputable: that there exist life-forms unfathomably different from our own, but deeply bound up with ours. The scientific explanation for the “fairy ring” circular pattern of mushroom growth is the underground presence of tiny threads called mycelia, that grow through the soil in a circular formation. As the biologist Merlin Sheldrake argues, such mycelia together form a primordial “mycorrhizal network” — a vast, underground matrix. And while this is not an “intelligence” in any sense we’d recognise, it is essential to plant life: an “ancient association” which “gave rise to all recognisable life on land”.

More than two centuries on from William Paley’s “watchmaker theory”, the received mainstream understanding of the world has little to say about mysterious underground mycorrhizal networks. Rather, it tends to describe a mechanistic universe, made of atoms, and devoid of governing intelligence or telos. For someone raised with this worldview, being stripped by hallucinogens of this frame of logic and causality can be exhilarating, eye-opening or simply terrifying. But even accepting that mind-altering substances can, well, alter the mind, even those who indulge would generally view the change as a mere chemical effect.

Last weekend, though, I found myself in just such a mind-altering experience without any such help. Trudging along a muddy path, I passed a “fairy ring” of mushrooms, and fell to thinking about my own hallucinatory adventures and what they suggest about perception. It struck me that even in the most mundane patch of woodland there’s still always something eerie at the edge of vision. As with the gleam of deer-eyes after dark, in the woods it takes only a minor shift in consciousness for all the godlings to creep back out from behind the trees.

Walking on, I passed a gate that seemed familiar and yet strange. I turned again, kept walking, and thought: oh look, another fairy ring. It wasn’t until several minutes further on that I realised that strange-looking gate was the exit, a route I’ve taken hundreds of times. The world suddenly resolved itself into the familiar again: I had passed the fairy ring twice, and was well on my way for a second lap round the woods.

Was it a fit of absent-mindedness? It felt as unmistakably an altered-state experience as being on mushrooms – except it was Saturday morning, and I was stone cold sober. It was like a message from the godlings: a reminder that the world only seems inert, because we’re used to seeing it that way.

And also, perhaps, a reminder that our age of disenchantment is on its way out. For inhabitants of mainstream modern British culture, raised in the birthplace of science and engineering, this may seem counter-intuitive. Fragments of old godlings may cling on in the very wild places, but Britain expelled our last major outbreak of millenarian religious fanatics to the New World, in the century of Bacon and Descartes. Our established church is so doctrinally tepid and reflexively conflict-averse, that hosting “silent discos” or installing helter-skelters in Anglican cathedrals prompts only the mildest of objections.

Those Anglican thinkers troubled by this are sometimes to be found yearning for a return of some sense of mystery. In “Re-Enchanting Christianity” the priest Dave Tomlinson speaks of how “Our world longs for numinosity: for a sense of awe and mystery, for sacredness, spirituality and enchantment, for something ‘more’ than the purely rational and cerebral”. And, he argues, “If the church fails to engage with, and cater to, this longing, it has no real future”.

Despite such efforts, there’s little of the numinous to be found in mainstream modern Anglicanism. But the wider world is on the opposite trajectory. I suspect the future belongs not to the sedate, polite mindset of logic and science to which Britain gave birth, and which by and large we still prefer, but the far more slippery, immanent, and enchanted one of millenarian religious narratives and wild forest beings.

My evidence for this is less the rise in religious extremism, noticeable though this has been especially in recent weeks. Rather, it’s signs that we’re losing the ability across the board to see the world in mechanistic terms: for example losing our ability to build or maintain complex systems, or even keep the roads repaired.

My best effort at explaining this phenomenon is that it’s happening because we are — at least compared with recent predecessors — simply ever less interested in the world of atoms, and physics, and cause and effect. Instead, leaders today are fixated on moral or symbolic dimensions. Evidence of this shift in priorities is everywhere, but perhaps its starkest instance might be what’s sometimes denounced as a “woke takeover of science” — but which could just as accurately be described as the re-subordination of empiricism to moral doctrine.

Even geopolitics has not escaped this re-subordination of reality to grand narratives. The neoconservative American wars, for example, were impelled at least in part by a religious impulse to globalise liberal democracy at gunpoint. Over the same period, too, they’ve been joined by other competing apocalypses. Believers in the climate variant conduct an escalating campaign of dramatic public protest. And the bitter dispute between Israel and Palestine has also, since the Nineties, accrued increasingly eschatalogical religious overtones.

The conflict in Palestine is of course complex. But contra the assertions of groups such as the New Atheists in the early 2000s that all forms of faith were destined for the scrapheap, grand apocalyptic narratives are growing not less but ever more influential. Along with the now endemic re-moralisation of governance, education, and science, this all presages a world that still (at least for now) has cars, and guns, and smartphones — but that runs not on the mechanistic logic of cause and effect, overseen by a remote divine watchmaker, but far more mercurial and sometimes violent logics of faith.

Is there any good news, amid this unsettling re-moralisation of the world? Well, if my Saturday-morning mushroom moment has a lesson it’s that mind-bending shifts in perception may be unnerving, but rich in insight. “Apocalypse” doesn’t just mean “end of the world” but also “revelation”. In Sheldrake’s view, the networked life of fungi can teach us to see ourselves as more porous ‑ something that, he argues, can help us to grasp our interconnectedness with other species, and thus perhaps to find new inspiration for tackling the ecological crisis.

We can perhaps extend this into the re-enchantment of public life: it may re-entangle us in frightening ways, but perhaps we’ll also be less lonely with it. Even so, those Anglicans calling for “re-enchantment” should perhaps be careful what they wish for. Outside the lamplight, the godlings were always looking back.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe