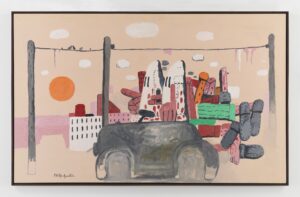

The Studio by Philip Guston (1969). © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

Two years late and trailing clouds of derision after the Boston Museum of Fine Arts didn’t feel it could mount the exhibition without a confetti shower of trigger warnings and leaflets advising on “Emotional Preparedness”, the Philip Guston retrospective finally opened at Tate Modern. A couple of days later came the Hamas massacre in southern Israel. After that, the Tate’s note advising that the exhibition has “some content relating to racism and antisemitism” seemed tame in the extreme. Racism and antisemitism you could find in plenty on social media and television, whether you were emotionally prepared for them or not. Your only option, if you weren’t, was to go back to bed and pull up the duvet, much as Guston liked to portray himself doing.

Otherwise, the retrospective is admirably respectful of the artist’s work and the people who come to see it. There are none of the admonitions against colonialist and sexist looking, for example, that marred The Rossettis at Tate Britain. Guston looks at whatever he wants to look at and — barring that brief allusion to antisemitism and the Ku Klux Klan as you enter — we are left in peace to do the same.

If anything, it is a bold curatorial stroke to begin the exhibition, not with examples of the young Guston’s early forays into social realism and surrealism but with a single full-blown, late-style comic-book canvas — “Legend” — in which the sleeping painter lets his nightmares spill across a flat mental plane so messy you can see why he has no desire to get out of bed. Here are objects that will become familiar as the exhibition continues: cigarettes, empty bottles of booze, bricks, a baton, a hoof, but also himself, the dreamer and hallucinator, all but crowded out of his own painting, wrapped up against the waking world, his brow rumpled, one boxer’s ear attached to his head like a can-opener, his spidery eyelid shut tight. Disturb him if you dare.

The artist’s mind rendered as a kitchen in which nothing has been washed or put away is more beguiling than disturbing, for all the violence of the brush strokes and the delusional pinks and scornful reds of the palette. I cannot explain the spindle-shanked horse running out of the picture, brandishing his tail like a scourge as he leaves, unless he’s a she — quite literally a nightmare. But the artist sleeps on, for all the sound of hooves smashing broken glass. “A world in turmoil,” the note on the wall comments. Yes, turmoil within and without — but too intriguing, not to say comic, for the turmoil to turn to anguish. However deranged the painter, the painting is all very bearable — a sort of joyous bonfire of the madnesses, as though Guston were painting himself sane. And then, having got you “emotionally prepared” for what’s still to come, the exhibition sweeps you back in time to Guston’s many false starts, that’s if it’s fair to call the means by which an artist discovers what he really wants to paint “false”.

Guston was good at this and that. Dipping his toe into the Italian Renaissance, surrealism, social realism, muralism, abstract expressionism — you name it, he could do it. He was born Phillip Goldstein, a name he changed for the usual reasons, to parents who had fled persecution in Ukraine. Just when or where is it a good time or place to be born a Jew? His reclusive father hung himself when Guston was still a boy, though what part the anti-Jewishness of early 20th-century America played in that — the alienation, the restricted opportunities (collecting junk was the best job he could find), the threats from the KKK — is a matter for speculation. But the Klan doesn’t haunt Guston’s imagination for no reason, and depression, in his greatest works, is only a dive under the covers away.

Not long after his father’s suicide, his brother died in a horrific car accident, after losing both his legs. The recurring motifs of nooses and twisted limbs need no more explaining than do the hoods of the Klan and the mountains of anonymous shoes. And maybe the name-changing accounts for the atmosphere of obsessive guilt. A bad start in life for the boy was a good one for the painter.

Crises of confidence and conscience nudged Guston from one sort of art and artistic commitment to another. He painted and won acclaim, but not from himself. “What kind of man am I,” he asks, “sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything” — he means Vietnam and the brutality of the world in general — “and then going into my studio to adjust a red to blue?”

He isn’t the first artist to have asked himself that. And it could have been the end of him as a painter. Political engagement had already taken up much of his time; what would another bout of engaged solemnity have yielded? As it happened, the artist in him found a way to make the refined aesthetics of “adjusting a red to a blue” a means of confronting the unrefined brutality he saw everywhere. As though to recreate the exhilaration of that creative resolution, the exhibition ushers us, along a narrow corridor, from the self-questioning Guston of earlier rooms, to the blazingly confident pink light of “Dawn”, a sublimely airy comic-strip send-up, firstly of the Ku Klux Klan and, by implication, Guston’s own early fear of them. Can there really be anything to be afraid of in these gormless hooded figures out driving in the early morning like children in a toy car, pointing out the sights of the city to each other, seeing the world for the first time, a lollipop sun just rising, candy-floss clouds floating in the sky, birds kissing on the telegraph wires.

It’s a glorious painting of the world waking up to wonder. So innocent does the jaunt feel that we can’t bring ourselves to ask whose twisted feet are sticking out of the boot of the nursery car. The Klan’s latest victims? Guston’s brother? Every menace and pained remembrance are grist to the mill — but ask what, in fact, is so illuminating about the painting and we have to root around in our own untidy kitchen of words to find the right ones. The painting takes the strain, let’s try that for starters. The painting disburdens — but disburdens whom of what?

There follows, in the next four rooms, one magnificently disburdening painting after another. “City Limits” depicts three hooded Klansmen hugger-mugger in another children’s car with giant Swiss-roll wheels, staring ahead in a bemused sort of way, excited to be out and about for all that their masks limit what they can see, if they can see anything. One is, of course, smoking, in the style of Groucho Marx, which doesn’t seem to bother the others. The painting is gorgeously claustrophobic, suggesting that the Klansmen enjoy one another’s company so much that being cramped is a pleasure to them. If the car is a prison, they are too stupid to mind and too impotent to do anything about it.

What world is this? Laurel and Hardy? Keystone Cops? The cartoonist Robert Crumb’s Keep on Truckin’?

Guston famously said of the Klansmen that “they are self-portraits” and in “The Studio” he goes the whole way with that fancy, standing a hooded figure at the artist’s easel, puffing black smoke, painting himself. It’s sublimely funny — the painter as Klansman engrossed in painting the painter as Klansman, an infinity of perpetuation, the crazier for the painter-Klansman having only two prison-door slits in his hood to see through, but reproducing those prison-door slits on the canvass with loving care. If Guston is somehow redeemed in the act of seeing himself behind the hood, is the hooded Klansman redeemed in the act of seeing himself as Guston? I don’t even know what sort of question that is. Does it bear on the nature of art or the nature of evil?

Here is the joy of the show, anyway. We look, muse, laugh, speculate, writhe a bit, which might be our own redemption from solemnity. How seriously to take Guston’s further identification with the Klansman — “I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan…what would it be like to be evil?” — I don’t know. Is Guston a metaphysician of evil? Is he Dostoevsky with red paint on his hands? Or are we closer to Chaplin guying Hitler?

I have to say I don’t experience the fear and trembling before these works that others report. Guston has so successfully eviscerated all horror from the Ku Klux Klan, so sublimely, if you like, made them himself in the course of making himself them, that we are taken to another plane of visionary delight. Not of aesthetic insouciance — there is no opting out of seriousness in these paintings — but of quizzical exuberance, as if to cast seriousness in a new light. Each of these late canvasses is a kind of obstacle course of memory, in which victory over evil is achieved by celebrating the absurd plasticity of evil’s presence, a random and yet purposive inclusiveness that takes in the artist and his perturbations, for the act of worrying is now his subject too.

Even “Flatlands”, which appears to show the artist’s imagination after the Flood — the scattered real and delusional detritus of his thoughts and associations: clocks telling different times, books, pointing fingers, legs without a body, a setting sun, Klansmen losing their way like malfunctioning robots, what might just be the chimney of an Auschwitz oven puffing its own cigar smoke — is calming, perhaps because it’s all over now, mastered in its random, godless profusion. Not “Look, I have come through,” but “Look, I am still looking.”

Almost the last painting in the exhibition is “Couple in Bed”. I don’t know if any artist more frequently painted himself asleep, but none surely painted a more poignant study of sleep and love in the service of art. Clutching his quiver of paint brushes for dear life, the painter buries himself into the safety of his wife. It’s a bed the poet Donne might have imagined — one little space an everywhere of devotion and achievement, a place of peace but not forgetfulness.

It is not unusual for art to make us happy. Mellow vistas and golden sunsets do the trick every time. What is far more rare is for happiness to be conjured out of horror.

***

The Philip Guston exhibition is on at Tate Modern until 25 February 2024.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe