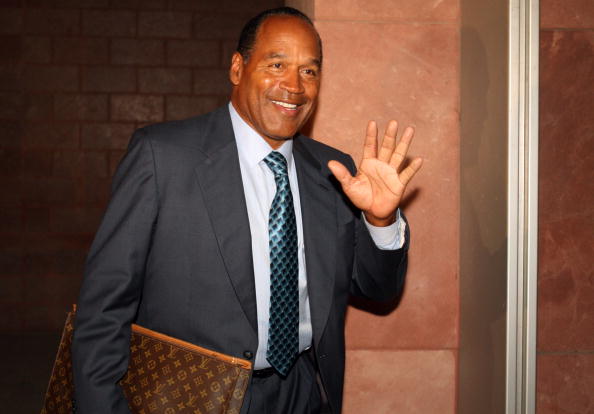

(Credit by Steve Marcus-Pool/Getty Images)

Hours after the news broke that OJ Simpson had died from cancer at the age of 76, I was sitting in a conference room, listening to an elevated but meandering discussion on the topic of forgiveness. Could absolution be empowering to those who bestowed it: a path to moral heroism? Or was it a relinquishing of power, of the favoured status conferred by victimhood? There was the question, too, of whether forgiveness could be cheapening — whether, for instance, there was a point at which forgiving a flagrant perpetrator of repeated harms was less an act of moral courage, than the mark of a rube.

One of the speakers, journalist Elizabeth Bruenig, recounted an incident that she described as the “perfect” act of forgiveness. Some 30 years ago, a woman was murdered. The killer was caught and convicted, and sentenced to death; she was also, remarkably, utterly unrepentant. She would express neither remorse nor regret. She would not even meet with the victim’s brother, who had intervened on her behalf to ensure that she would not be executed.

And yet, he forgave her anyway.

I suppose there is something perfect about that — in the same way that a perfect work of art or music can fill you with sadness and longing. To Bruenig, affording grace to a person who not only did not want forgiveness but was liable to throw it back in your face was an example of profound moral courage. I don’t disagree, but another, more cynical thought also occurred to me: what else was he going to do?

There’s a saying that I’ve seen printed on pillows and such, in those shops where they sell scented candles emblazoned with LIVE LAUGH LOVE: it reads, “Let go, or be dragged.” It’s trite, but it captures something about the price of holding a grudge — how the weight of an injustice can grow to become a greater burden than the original offence. That wound you refuse to allow to heal will fester, and deepen, until you’ve caused more damage through your scab-picking than the person who cut you in the first place. You may desire retribution, but you may also find it unavailable to you, and then what? The only thing left is forgiveness.

This was when I started thinking about OJ Simpson, who in some ways strikes me as a funhouse mirror version of the Bruenig’s unrepentant killer. The contours of OJ’s life after his acquittal for the 1992 killings of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman, which he definitely committed, have been aptly described by Oliver Bateman as “posthumous” — that is, long before OJ’s actual death, to a certain segment of the public, he might as well have been. We wished he were. And his existence after the trial, per Bateman, made for “a striking modern-day reflection of how legacy and infamy intermingle in the digital age”. Insofar as OJ did have a life after getting away with murder, he owes it largely to the sense among members of Gen Z that history before the internet simply didn’t exist; the most sympathetic audience to Simpson’s comeback performance were always the ones too young to have actually seen its first or even second act.

Those of us who do remember the trial, the car chase — or Simpson’s reputation for domestic violence — were less inclined to welcome him back into polite society. But even those who protested most vehemently against his reemergence could only do so for so long, before the whole endeavour seemed pointless, especially in the face of Simpson’s winking remorselessness. Remember, this was the man whose brilliant plan after being acquitted of murder was to confess to the killings by way of a six-figure deal for a book titled If I Did It. And if the title was a provocation, then the original jacket design — the I DID IT in eye-catching red, with the “IF” printed in letters so pale that it couldn’t be seen at a distance — elevated it to the level of farce.

The brazenness of it was such that, at the time, it seemed like the only option we had was to laugh it off or lose our minds. OJ’s acquittal despite his obvious guilt was no longer just a tragedy but a terrible joke — one we were all in on whether we liked it or not. And the question of whether he might be forgiven (not that he was asking for this) became inextricably entwined with the question of whether we could forgive ourselves for our inability to do anything about it — for a miscarriage of justice so complete that the only catharsis was to make it a recurring gag on Saturday Night Live. Imagine the relief when Simpson managed to get himself sent to prison anyway, this time on a robbery charge for which it hardly mattered if he was guilty or not. Nothing could undo the appalling error of his acquittal, but here, at least was a way to halfway correct it. The only problem, and nobody wanted to think about this part, was that he would eventually be let out again.

And then he was.

An uneasy dynamic has existed between the world and OJ in the seven years since his release. Unlike Mike Tyson, who finished serving a prison sentence for rape the same year OJ was acquitted of murder, and who has since found his footing in popular culture as a sort of lovable drunken uncle figure, OJ remained on the fringes of public life; he never won complete rehabilitation. But nor was he saddled with the baggage of a Bill Cosby, a Roman Polanski, or even a Woody Allen (nobody ever feels compelled, for instance, to issue a disclaimer about their distaste for OJ before professing an appreciation for Roots or The Naked Gun series, both of which featured him as an actor). I’m still trying to understand the calculus whereby one person is merely (and not even necessarily credibly) accused of a bad act against a woman and spends the rest of his life a pariah, while another, who most definitely killed two people, can make something of a public comeback in which his criminal past becomes part of his charm.

Or perhaps it was precisely because of OJ’s utter irredeemability that any sort of redemption was possible: that once someone has done the worst thing, even the slightest glimmer of humanity might feel encouraging. It’s a familiar trope in fiction, the monster you find reasons to root for. Hannibal Lecter, Dexter Morgan, Raskolnikov, Macbeth. These are bad men, they do bad things — but we know this only in the abstract, without any accompanying wound. These are bad men, they do bad things… but not to us, so maybe it’s sort of okay?

Of course, to the victims, it’s not okay. And while Simpson may have travelled a peculiar sort of redemption arc in the final years of his life, there is still a difference between rehabilitating one’s brand — something a person can do for himself — and forgiveness — which can only be bestowed by someone else. When we abandon hope of seeing justice done because we’re too tired, or too disgusted, that’s something, but it’s not forgiveness. Nor is it forgiveness when the people bestowing it upon you have no real sense of the harm you did. And whatever status Simpson enjoyed as an internet personality, he was never let off the hook by the families of his victims, who remained at once shattered and animated by his crimes. The most memorable statement on the day of OJ’s death was made by Ron Goldman’s father, Fred, who never stopped insisting on the necessity of justice long after the rest of the culture had made its uneasy peace with the murderer: “The hope for true accountability has ended,” he wrote.

It’s possible to imagine a world in which this remark was one of resignation, and also of relief; after more than 30 years, with his son’s murderer dead, surely nobody could blame Fred for letting go now. (Indeed, if you continue clinging to a remorseless killer after he himself has died, the question arises of which immortal realm you might end up being dragged to.) It’s also possible to imagine a world in which this could have become one of those perfectly imperfect moments of forgiveness, for lack of an alternative. But this is not the path forward that Goldman proposes. “[Despite] his death,” he wrote, “the mission continues; there’s always more to be done.”

In other words, when the hope for vengeance is lost, forgiveness is one possibility, but not the only one. Another sort of hope might takes its place, and with it, another sort of power: not the status of the permanent victim, or the self-satisfaction of the moral hero, but the purpose of the survivor.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe