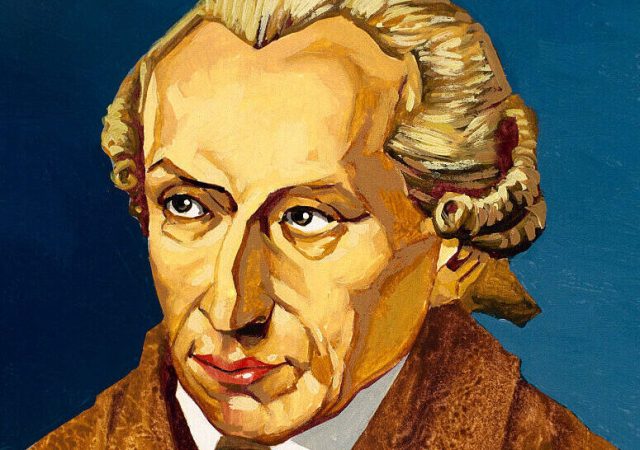

(Ipsumpix/Corbis via Getty Images)

Poor old Immanuel Kant, scourge of many an undergraduate essay crisis, whose 300th birthday fell this week. Was ever any other major intellectual figure put through so much painful contemporary “rethinking”?

According to the late political theorist Charles W. Mills, Kant’s oeuvre contains the resources to establish a variety of “Black radical Kantianism”. Numerous others have presented him as a proto-feminist, with a recent monograph by US-based philosopher Helga Varden claiming that “despite his austere and even anti-sex, cisist, sexist, and heterosexist reputation, Kant’s writings … yield fertile philosophical ground on which we can explore … abortion, sexual orientation, sexual or gendered identity”. All of this is quite unexpected for a 18th-century Prussian bachelor of Lutheran upbringing, of the opinion that sex should occur only within Christian marriage, black people were natural slaves, and women unfit to have a vote.

Also surprising, at least initially, is the fascination Kant’s systematic philosophy still exerts over many in academia, despite the famed dullness of his prose. In an unusually striking phrase, he once wrote of “the miserly provision of a step-motherly nature” — and indeed, step-motherly nature doesn’t seem to have been liberally doling out the bantz the day young Immanuel was born. According to one biographer, he was “extremely stern with himself from his early youth”: determined to be economically independent, “because he saw in it a condition for the self-sufficiency of his mind and character”. Throughout his life, he never left his home city of Königsberg; later on, his neighbours there would set their watches by his exactly timed daily constitutional walks.

Valiant attempts of hagiographers to make him seem like a fascinating demimondaine only reinforce the impression of squareness. “He was a very social type who often went to parties and sometimes drank too much,” protested one fellow German author to the Guardian 20 years ago, a little too insistently. “At times Kant could not find the street where he lived because he was so inebriated.” There were also “amorous interests” in at least two women, it was reported, though no evidence the relationships were consummated.

If not his innate charisma or worldliness then, what explains the lingering attraction of Kant’s elaborate philosophical system to today’s thinkers? For many, it is surely the ingenuity with which he dealt with a number of disquieting sceptical challenges that emerged during the Enlightenment. Over the course of several mature works, Kant built an intricate cathedral of interlocking justifications, providing support for certain traditional assumptions that new scientific discoveries and encroaching atheism would otherwise seem to leave dangling in mid-air.

For instance: answering to David Hume’s worry that humans could neither directly observe nor otherwise prove the existence of fundamental natural laws such as the connection between cause and effect, Kant got rid of the underpinning assumption that the human mind and the natural world were wholly separate. Instead, in a reversal he likened to Copernicus’s revelation that the Earth revolved around the Sun and not the other way round, he wove an understanding of such laws into the fabric of sensory experience, so that allegedly it now made no sense to seriously doubt them.

Faced with the creeping fear that there could be no free will in Newton’s mechanistic universe, Kant then leaned upon his own picture of the physical world as a realm of partly mind-constructed appearances, and placed the free, unmoved-yet-moving self safely in a separate realm beyond it. To the increasingly urgent complaint that without God as a foundation, traditional Christian precepts must surely lose their authority, he responded by instead putting free will and autonomous human reason at the heart of objective moral decision-making, conveniently preserving many austerely Protestant-looking practical conclusions as he did so.

In all of this Kant gave the cognitive faculties a crucial role, painting the mind not just as a discoverer but also as a partial inventor of our universe and its fundamental rules — a suggestion flattering to susceptible brainboxes in universities, secretly pining for a superhero role in life befitting of their intellectual talents. And despite the often flatfooted and prosaic presentation, there is also a thrilling intimation of spookiness to the metaphysical picture Kant ultimately offers readers: on the one hand, the world of knowable appearances, and on the other, a supernatural realm of things-in-themselves, whose existence humans cannot apprehend directly but only infer.

But perhaps the aspect of Kant’s thought most attractive to today’s professional academic is that — like many of them — he is an intellectual conservative of sorts. Though he rearranges the metaphysical furniture, sometimes fairly radically, he usually leaves his fellow citizens sitting almost exactly where they were beforehand. The structure of the universe is still predictable; humans continue to have free will; it is still the case that one shouldn’t kill, break promises, or lie. Effectively, Kant often starts with conclusions he wants to preserve and then works backwards.

To some extent, this is also the strategy of some of his modern interpreters, beginning with a particular set of now-fashionable political conclusions, then casting about in Kant’s writing for the resources to prop them up (usually, by making extensive use of his emphasis upon the importance of freedom and self-governance). Though in his ethics Kant railed against using another person instrumentally as a “mere means” to your own personal ends, in practice commentators don’t seem to pay much attention to that bit, as they haul him off down the gender clinic or to the BLM march. Superficially, it may look sexily avant-garde to employ the ideas of a thinker as buttoned-up as Kant, in order to underpin arguments for the rights of people to have polyamorous orgies or to cut body parts off at will. In reality, though, these anachronistic uses of his thought would never have escaped the seminar room and made it out into the wider world alive, had society not already rendered it perfectly permissible or even profitable to pursue such endpoints.

Of course, there are also differences between Kant and the new crop of academic apologists for contemporary mores. Perhaps the most obvious is that, over the last 300 years, hundreds and thousands of people from many walks of elite life have read and responded to Kant’s works; a trend helped along by the assumption, popular until relatively recently, that a grasp of the central figures in Western philosophy was a requirement upon any decent education. But these days, almost nobody who isn’t already studying or researching philosophy reads academics like Mills and Varden. So who or what are they doing it for, exactly? It would be madly grandiose to think that, in the 21st century, anyone has ever been converted to black radical politics or pansexual people’s rights by reading opaque monographs from academic presses priced at £25 a pop.

A more charitable take, perhaps, is that both Kant and those modern thinkers loosely inspired by him are each using reason to perform a kind of sense check upon certain key presuppositions of their time. They start off with some folk-conclusions that are believed by many, though with no clear idea of why; next, they ask themselves whether there are convincing rational arguments available that might support those conclusions, and so lend them extra weight. In other words: can philosophers, with all their specialist technical skills in argument construction, produce a solid-enough rational scaffolding for some of the important-looking things that people already think?

But if this is the strategy, it is a risky one. The more byzantine the layers of argument offered for the truth of a particular set of presuppositions, the more keenly the suspicion grows that it might have been just as easy — or certainly, no more difficult — to offer neat and ingenious arguments that seemed to show exactly the opposite. Kant’s sprawling system, with its host of interwoven technical assumptions ranging across metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, aesthetics and politics, already invites this worry; by the time commentators start to lean upon that system in order to justify social-justice mantras about abortion or cis privilege, the edifice looks in danger of collapsing.

Or perhaps these present-day commentators assume that the only way to redeem Kant from his intermittent episodes of racism and sexism — to cleanse him of those everyday 18th-century sins — is to demonstrate that, despite appearances, his philosophical system has the potential to generate a progressive position on those very matters about which he was so reactionary. For some academics, this may well be the best explanation: attempting an absolution of sorts for their hero.

Either way, it’s hard not to conclude that in thinking about Kant’s legacy, we are better off going back to the extremely rich source material directly, and trying to see it in its proper historical context — for better or worse. There is no need to mess around with any quasi-religious new adaptions. It is a strange irony that, in the 300 years since Kant was born, those working in universities only seem to have got more puritanical.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe