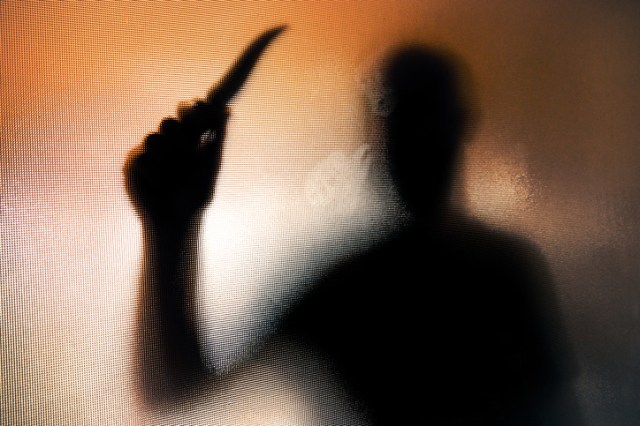

(Credit: Getty)

Another day, another report of a child stabbing another child. On this occasion, it was in the comprehensive school in the former mining valley of Ammanford in Wales, where a teenage girl has been arrested after three were left injured, one a fellow pupil. But these stories have become so common that they’ve almost lost their power to shock. Instead of examining these crimes, we have allowed them to become an ambient menace: a rolling cycle of arrests, trials and ever-growing violence. And this is an abdication: we are all partially guilty for pushing the cold steel blade.

Explanations for this escalation in violence are framed in two distinct ways. The first sees it as a question of individual responsibility and free will. The perpetrator must assume sole culpability. If there are other factors at play, they are thought to be immediate ones: from bad parenting to the grooming cultures of gangs. There is no doubt some truth to this, especially the way gang culture promotes and glorifies violence, which is also inseparable from that of the drug economy. But most would also agree that when it comes to youth violence, given the age of the assailants, the account needs to factor in a wider question of blame. After all, can a child be held fully responsible for their actions?

The second approach focuses on those broader social conditions, or what sociologists would identify as embedded “structural factors”, which include various measures for deprivation. In this reading, insight is less concerned with dangerous individuals than with society more generally. This is the approach associated with Henry Giroux, whose focus on what he terms “the war on youth” addresses adolescent rage within a framework that considers social neglect and criminalisation. If we choose to emphasise not agency but social ecologies, if there is blood on our streets, it’s not just the perpetrators that should concern us.

To have a full sense of the problem, though, we must also factor in the conditions of austerity and the major cuts to youth services which once provided children with educated alternatives to gang lives. There is a clear correlation between cuts in funding after 2008 and the exponential rise in knife violence. Before the pandemic, an official Parliamentary report specifically highlighted the link. And since this hollowing-out of civil society began, there have been clear warning signs that something was being neglected, and was allowing violence to brew.

Particularly instructive were the inner-city riots of 2011. Driven largely by youths in cities across the UK, these mindlessly destructive events demonstrated what the late cultural theorist Stuart Hall pointed to as revealing of nihilistic tendencies born of a real sense of alienation and a dispossessed future. The eminent sociological theorist Zygmunt Bauman concurred, referring to them as protests without aim, a causeless revolt for a post-political generation who no longer believe their future can collectively be steered in a different direction. As Hall wrote:

“Some kids at the bottom of the ladder are deeply alienated, they’ve taken the message of Thatcherism and Blairism and the coalition: what you have to do is hustle. Because nobody’s going to help you. And they’ve got no organised political voice, no organised black voice and no sympathetic voice on the left. That kind of anger, coupled with no political expression, leads to riots. It always has.”

Since then, some would claim that social alienation has found more genteel avenues to march along: there has been an exponential rise in youth protest, from concerns with ecology to the Black Lives Matter movement. Yet any close study reveals how the impetus and main participation of such movements remains a largely middle-class preoccupation. And too often, the lauding of this newly awakened generation affirms the wonders of digital activism, which has been a catalyst for a new kind of political community building. But digital technology isn’t solely a progressive catalyst — the same is directly responsible for compounding the violence we are seeing on the streets.

For middle-class youths, the internet allows them to advertise themselves as the new vanguard of digital activism, which from time to time sees them taking to the streets or damaging works of art without any real risk to their personal safety. For children from poor backgrounds, however, what social media exposes them to are glamorous lifestyles that will probably remain beyond all reach, while ensuring the visual records of their impoverished lives will continue to follow them around. Given their conditions of acute poverty, many young people prefer to live virtually, playing violent video games and scheming an escape from their surroundings. And when hit with the rub of the real world, these forces of brutality and social aspiration only merge and warp.

That the digital revolution has diminished the wellbeing of children is now well-established. The addictive effects of technology and its impact on anxiety, mental health, attention spans, and general ability to navigate the world in a more tolerant and open way points to a generational problem which many would readily accept. And yet for too long we have treated the outlying social issues of our time as immune from this diagnosis.

While children, like the rest of us, have become forced witnesses to spectacles of violence and voyeurs to daily sufferings, they are also mirroring the brutalism and loneliness that fills digital landscapes. We live in an age defined by what I would call “hyper-primitivism”, occupying digital nervous systems of hyper-arousal, where everything is tethered to emotional reactions and responses in an excessively sensitised way. It smothers our genuine respect for others. And instead of bringing humans together, it propagates tribalism and division as creeds of hatred and intolerance. Individualism and rampant disregard becomes the norm. And emotion is liberated from responsibility.

The consequences are all too shocking. Online battles and disagreements that take place in virtual bubbles are finding their way into the material world: slashed bodies on digital screens make their way into the real world as bloodied corpses on our streets. And in a deeply tragic and symbolic way, one item has come to stand out as the symbol for this new reality. The weapon of choice, and perhaps the only kind of leveller on city streets: the zombie knife. Garishly coloured, unrealistically huge, they represent the merging of the artificial and the alienated.

The rise of the zombie genre in the violent virtual world is instructive. Born out of the Sixties concern with consumerist culture and the soul-destroying landscapes of the American shopping mall, it has also become one of the leading products defining the digital age for youth. Yet the zombie also evokes a particularly nihilistic sense of the world, where the only strategy is one of pure survival. As depicted in the “Men Against Fire” episode of Black Mirror, seeing humans as zombies facilitates dehumanisation, which makes the violence easier to afflict. We only need to look at popular games children are playing, from the Resident Evil franchise, The Last of Us, and Dead Island, onto other popular series like Fortnite and Grand Theft Auto, to note the prevalence of slasher killings. The zombie knife brings this utter hopelessness into reality, a weapon for a place where children place no value on the lives of others.

Mindful of this, it’s hard not to see the current problem of youthful killings as a novel kind of nihilism, executed by children who no longer have any belief in the future. We know that the more we weaponise the world, the more we are likely to usher in its obliteration. That same logic should be applied to the streets. The fact that children carry knives is the surest indication that their means of navigating space is by being prepared for a violent ending, and taking another life should that eventuality arise.

So what can be done about this? It’s not enough to say we just need better regulation, and societies shouldn’t expect parents to carry the responsibility. When the young die, we only see the body lying in the street or on the hospital bed. But there are other forces putting them there. Knives have become more than a weapon. They cut open the illusions of a digital world.

Faced with this situation, it’s time that our society started taking seriously the desire for such violence. Hyper-primitivism is all about desire, creating emotional states on virtual spaces, which then leave us feeling helpless once we enter back into the real world. For young people who spend most of their lives feeling powerless, violence is attractive because it has real-world effects. Violence fills the void.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe