If the American futurist R. Buckminster Fuller was right, as he always was, then the boundaries of human knowledge are forever expanding. In 1982, Fuller created the “Knowledge Doubling Curve”, which showed that up until the year 1900, human knowledge doubled approximately every century. By the end of the Second World War, this was every 25 years. Now, it is doubling annually.

How can humans possibly keep up with all this new information? How can we make sense of the world if the volume of data exceeds our ability to process it? Humanity is drowning in an ever-widening galaxy of data — I for one am definitely experiencing cognitive glitching as I try to comprehend what is happening in the world. But being clever creatures, we have invented exascale computers and Artificial Intelligence to help manage the problem of cognitive overload.

One company offering a remedy is C-10 Labs, an AI venture studio based in the MIT Media Lab. It recognises that our ability to collect data about the human body is rising exponentially, thanks to the increasing sophistication of MRI scans and nano-robots. And yet a radiologist’s workload is so high she can’t possibly interpret all that data. In many cases, she has roughly 10 seconds to interpret as many as 11 images to judge if a patient has a deadly condition. It’s far quicker and more reliable to use AI which, in combination with superfast computing, can scan the images and find hints of a problem that a human’s weary eyes and overloaded mind might miss. This will save lives.

Yet AI is a greedy creature: it feeds on power. Last year, the New York Times wrote that AI will need more power to run than entire countries. By 2027, AI servers alone could use between 85 to 134 terawatt hours (TWH) annually. That’s similar to what Argentina, the Netherlands and Sweden each use in a year. Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, realised AI and supercomputers could not process all this data unless we find a cheaper and more prolific energy source, so he backed Helion, a nuclear fusion start-up. But even if we can power the data, can we store or process it at this pace?

One answer to the storage problem is to make machines more like humans. As Erik Brynjolfsson says, “Instead of racing against the machine, we need to race with the machine. That is our grand challenge.” How will we do this? With honey and salt. Earlier this year, engineers at Washington State University demonstrated how to turn solid honey into a memristor: a type of transistor that can process, store and manage data. If you put a bunch of these hair-sized honey memristors together, they will mimic the neurons and synapses found in the human brain. The result is a “neuromorphic” computer chip that functions much like a human brain. It’s a model that some hope will displace the current generation of silicon computer chips.

This project is one part of a wider “wetware” movement, which works to unite biological assets with inanimate physical ones; organisms and machines. Yet the wetware movement sees DNA, not honey, as the ultimate computer chip: salted DNA, to be precise. The salt allows DNA to remain stable for decades at room temperature. Even better, DNA doesn’t require maintenance, and files stored in DNA are cheaply and easily copied.

What makes DNA so special is that it can hold an immense amount of information within a miniscule volume. “Humanity will generate an estimated 33 zettabytes of data by 2025 — that’s 33 followed by 22 zeroes,” says the Scientific American. “DNA storage can squeeze all that information into a ping-pong ball, with room to spare. The 74 million million bytes of information in the Library of Congress could be crammed into a DNA archive the size of a poppy seed — 6,000 times over. Split the seed in half, and you could store all of Facebook’s data.”

Yet even if — thanks to honey and salt — we can capture, store and process this fast-growing galaxy of data, what will humans do with it? Will we actually make sense of it? Put another way, does the human brain have a Shannon limit? The American mathematician Claude Shannon clocked that there’s a “maximum rate at which error-free data can be transmitted over a communication channel with a specific noise level and bandwidth”. Traditionally, the Shannon theory is applied to technology: a telephone line, a radio band, a fiber-optic cable. But Brian Roemmele argues that the human brain, too, has a Shannon limit — and that it is 41 bits per second, or 3m bits per second if it’s visual input. With the breadth, depth and speed of new information doubling all the time, can the human mind keep up?

Probably not. The weight of all this knowledge is crashing against the limits of the human mind. We may be able to compress the whole of Facebook’s information to half a poppy seed, but can the human mind survive contact with that poppy seed? Perhaps not. Something’s got to give. It will be us.

The Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan suggested this years ago. He thought that information overload changes how we think and act. When there is too much news to process, we stop assessing individual news stories and start analysing the source: I don’t trust it if it came from CNN; I trust it if it came from Fox News. Too much information makes us more tribal and less analytical.

Just as political tribalism is a human response to knowledge overload, so, according to Princeton’s Julian Jaynes, is consciousness itself. Jaynes argued that consciousness is simply a coping mechanism humans developed once we started living cheek by jowl in ancient cities in the 2nd millennium BC. The stress of managing interactions between strangers with very diverse cultural backgrounds, languages, and behaviours was so great that the human brain increasingly split the work into two hemispheres, the left and right lobes, and began to analyse and absorb. This was the beginning of consciousness: of listening to the voices in our heads, turning to metaphor to explain reality and developing the skill of introspection.

Later, Renée Descartes proposed another split. This time, humans would split the head from the body. The Cartesian Revolution ruled that the left side of the brain handles the serious stuff: logic, rationality and the scientific method. These endeavours were deemed worthy of our time and energy. The right-brain — which includes emotions, anything mystical or inexplicable or unprovable — was cast aside along with the body. The State got the decapitated head, and the Church got the body.

Now, AI is using its God-like powers to reunite them. With the development of AI and wetware, we are witnessing the beginning of the end of the Cartesian era of human history. The split between the mind and the body no longer makes scientific or practical sense: humanity is increasingly knitting the two back together again and approaching reality more holistically (not that they were ever actually separate — we humans have always been wetware).

This realignment is changing the way we manage risk and uncertainty, for instance in financial markets. David Dredge, a former colleague of mine and the founder of Convex Strategies, argues that it’s not only the end of the Cartesian era, but also the end of the Sharpe World. For a long time, financial markets have relied on the Sharpe Ratio, which compares the return of an investment with its risk. But, in this new post-AI environment, that old measuring stick no longer works. Dredge refers to the concept of “Wittgenstein’s ruler: Unless you have confidence in the ruler’s reliability, if you use a ruler to measure a table, you may also be using the table to measure the ruler.”

In the post-AI world, it may be that all the data starts to fall into patterns, perhaps fractal-like repeating patterns. Our job won’t be to guess the price of the S&P or the Yen anymore but to rely on AI and supercomputing to tell us how all financial instruments are moving in repeated patterns over the course of time. We’ll stop focusing on price moves and start looking at the movement of the financial system as a whole. As Dredge says: “It is the divergence that matters and ever more so the greater the scale of the variation.” In other words, volatility at the global financial systems level is very different from volatility at the level of the US bond market. Perhaps this means in the future we won’t have specialists in US government bonds or British government bonds. Maybe we won’t even have bond specialists. Instead, we’ll have people who are reading the patterns of all financial instruments in all markets at once. This brings a whole new meaning to what we call global macro.

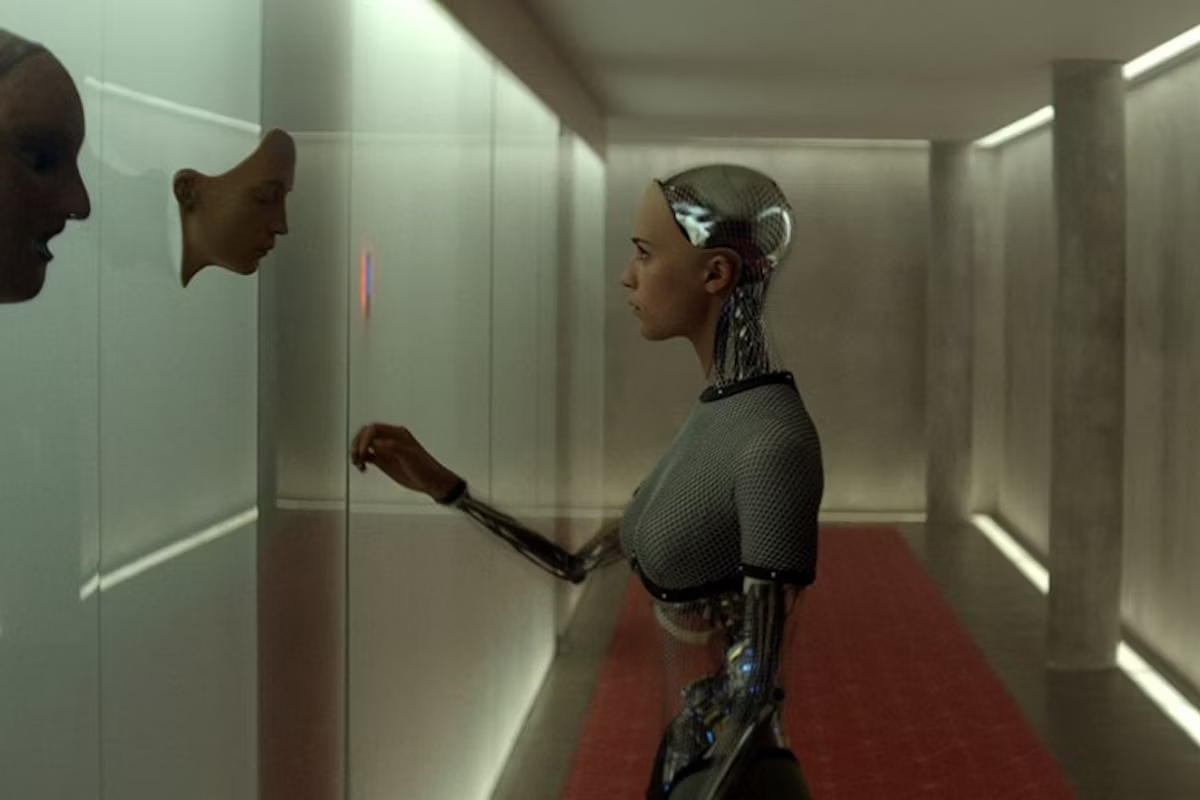

So, wetware-powered AI isn’t just about processing more information faster: it is about reducing uncertainty. Its rise will also profoundly change how humans think about the nature of reality — both in finance, and more generally. It will require humanity to delve into the subject of consciousness that hasn’t been considered worthy of study in the Cartesian era. The thinking nature of AI presents uncomfortable questions: is it sentient, or will it be? Will its decision-making supersede human decision-making? Will the volume of data overload mean that human minds can’t make sense of things that machines can understand perfectly? Will we eventually outsource decision-making to AI powered by neuromorphic chips that form a brain that is vastly better informed and more conscious and conscientious than any one human brain? This means letting go of the details and getting into the flow of this new emergent superhuman consciousness that moves faster than our minds.

Can we handle this reduction of uncertainty? Humans are upping their game all the time: we went from storing and sending data on megalithic stone carvings to computer chips with silicon substrates, glass substrates and now honey and salted DNA substrates. Accepting the gift of this emergent consciousness will change humanity. It will remind us that we humans are a fluid and emergent phenomenon ourselves. We won’t be specialists surfing within the web anymore, we’ll be polymaths surfing the whole of the web. This is more than a Renaissance. It is something new — and we are present at the creation. It’s a bittersweet moment: but change is happening, like it or not. AI demands not only nuclear fusion but a fusion of all our cognitive capabilities and consciousness, whether human or human-made. Only by improving the quality of our emerging consciousness, and the conscious qualities of our machines, can we hope to stay afloat in that ever-swelling ocean of knowledge.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe