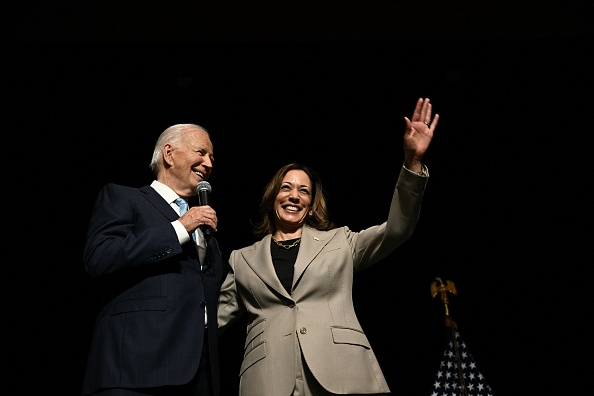

Can Kamala Harris disturb the regional balance of power? (Photo by BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images)

It has become conventional wisdom in the waning days of Biden’s presidency to say that America has launched a new era in economics. Concepts like industrial policy, trade protectionism, antitrust enforcement and child subsidies — all once verboten during the heyday of globalisation — have been dusted off by a new generation of policymakers.

Taken together, several commentators believe these trends mark the end of neoliberal governance and the beginning of a different consensus in Washington — and in a narrow sense they are right. Biden’s policies do harken back to aspects of the New Deal and Cold War liberalism, while the populist Right have promoted their own vision of economic reform. But, for reasons intrinsic to America’s party system, neoliberalism’s final chapter has yet to be written.

There are real obstacles to consolidating a new consensus — and they go beyond the obvious influence of each party’s most prominent donors or the rulings of conservative justices. The current geographic division of political power in the United States between conservative red regions and progressive blue ones reinforces a status quo which greatly privileges economic elites in both party coalitions and curtails the possibility of faster action on urgent issues.

Compared with the latter half of the 20th century, when Democrats and Republicans contested a broad range of states and a handful of landslide elections took place, the strategies animating today’s party coalitions are primarily defensive. Bold incursions by either party into the other’s strongholds are now uncommon. And the Democrats’ big-tent posture under Kamala Harris is unlikely to disturb this balance of power.

The regional pattern of party dominance is reflected in the small set of swing states that have determined presidential elections since the 2000 contest between Al Gore and George W. Bush. But it is illustrated just as much, if not more so, by the rise of one-party control in a majority of US states. Democrats currently hold “trifectas” (the governorship plus a majority in a state’s upper and lower chambers) in 17 states, while Republicans have a veritable lock on 23. In an echo of past “sectional” distributions of party control, geography would appear to denote ideology in the first decades of 21st-century America.

And this regional dynamic seems to go hand in hand with an accelerating political realignment or class “dealignment”. This phenomenon, wherein since the late Nineties the GOP has attracted far more working-class voters than it used to while the Left has won the vote of more and more upscale voters, appears to wary progressives and eager “New Right” thinkers alike as a harbinger of a generation-defining political realignment. But, while that is partly true, what is more salient is that the parties now coalesce support on the basis of identity-driven loyalties and deeply felt negative partisanship, and are then able to limit their economic promises, hewing instead to vague rhetoric about growth and opportunity. Campaign strategists continue to prioritise mobilising core supporters, rather than courting workers who are wavering in their partisan affiliation or engaging the country’s estimated 80 million disaffected nonvoters.

Consequently, the respective opposition party in key regions has become feeble to the point of being virtually nonexistent. Modern Democrats have been routed in several Rust Belt and Southern districts where New Deal liberals once swept the polls, while Republicanism, once a vehicle for Reaganite yuppies and wealthy suburbanites, has been reduced in the citadels of high finance and the multicultural elite to an ornery badge of non-conformity. In both cases, wage-earners who want a bigger share of the economic pie and more accountable politicians must contend with de facto one-party rule in much of the country. This is a situation that has rarely favoured more egalitarian outcomes.

The past 30 years might have altered the composition of the Republican and Democratic coalitions, but it has also calcified the power of regional and national elites. The political realignment has failed to catalyse any fundamental change of priorities in Republican strongholds. With few exceptions, Republicans, in spite of Trump’s 2016 foray into economic populism, remain beholden to big players in older extractive industries and a host of middle-men magnates. The combined lobbying efforts of these interests prevent local- and state-level Republican officials from reorienting their party branches to populist ideas. The GOP response to teachers’ strikes and unionisation drives at auto plants and Amazon distribution centres has predictably ranged from indifferent to hostile.

Conservative thinkers advocating substantive overtures to labour still have high hopes for Trump’s running mate, Ohio senator J.D. Vance, and a few other “anti-globalist” Republicans in the Senate. But remove the ever-churlish Trump from the equation and the GOP all but loses its insurgent garb. Belying Trump’s fading anti-establishment message, rising GOP leaders such as Georgia governor Brian Kemp have staked their reputation on attracting high-profile business investment and pet development projects. Ribbon-cuttings, not a showdown with American oligarchs, are what motivates them. Vintage Trumpian populism shows no sign of supplanting the traditional business conservatism that still guides local GOP elites.

By contrast, the Democratic Party certainly appears more attentive to the needs and hardships of its own lower-income base. Indeed, the party’s self-image as the vehicle of social uplift has endured despite attracting a growing share of wealthy and college-educated voters in recent election cycles. Even though Democrats have haemorrhaged support from working-class whites, they continue to heavily draw black and other minority wage-earners as well as white progressives who want a stronger welfare state. On the basis of this alliance, it is hoped by the party’s reformers that if Harris wins the presidency she will continue to legislate in Biden’s “post-neoliberal” vein.

This optimism derives in part from stalwart Democrats’ rose-tinted view of the records of blue cities and states. As housing costs began to soar last decade, a handful of Democratic governors and mayors billed themselves as reformers ready to take on powerful real estate interests and build more affordable housing. They likewise tried to aid their working-class constituents through minimum wage hikes, paid sick leave, experiments in fare-free public transit, and efforts to raise enrolment in health insurance subsidised by the Affordable Care Act, Barack Obama’s key social programme.

Scratch beneath the surface, however, and one finds little has been done in major US cities to alleviate economic insecurity. Whether due to permitting obstacles or vested interests, the housing shortage is now a full-blown crisis. And the problem is only bound to get worse. Nationwide, a record-breaking twelve million renters now spend half their income on housing while nearly seven million units need to be built for heavily rent-burdened low-income people. This shortfall stands in contrast to Harris’s plan to build just three million homes.

Previous efforts to ensure wages kept up with living costs have likewise proved insufficient. App-driven gig work has become ubiquitous in large metro areas, testing Democrats’ commitment to full employment and pro-worker principles. From California to Massachusetts, Big Tech has successfully fought legislation that would classify gig workers as employees and have tried to resist industry-specific minimum wage bills. Despite the Biden administration’s investments in infrastructure and clean energy, urban economies continue to reflect neoliberalism on steroids: the pace of gentrification, pushing poorer residents to outer neighbourhoods, has put them at a further disadvantage when it comes to finding decent work.

These trends have heightened the perception that Democrats cater to affluent professionals while offering, at most, minor relief to the wage-earners who provide their margin of victory in major elections. That is bad enough for a party once considered to be the tribune of workers. Rather absurdly, however, the Democratic Party’s deference to tech, real estate, and finance has been accompanied by ham-fisted choices which have exacerbated quality-of-life problems for many working families. These range from radical misjudgements influenced by social justice paradigms to less obvious but still pernicious forms of incompetence.

Most notoriously, recent ill-conceived experiments in drug decriminalisation under the framework of “harm reduction” in cities such as San Francisco, Seattle and Portland, Oregon eroded public safety enough to dampen economic activity in core neighbourhoods. Those case studies have since become a source of ridicule and embarrassment for Democrats trying to thread the needle between maintaining vibrant commercial centres and reforming the criminal justice system.

Unfortunately, other trends only underscore the ways in which blue-city governance has become strangely inept. Since the pandemic, truancy rates and learning loss in public schools have exploded — an outcome that more and more analysts attribute to extended remote-learning protocols in Democratic districts. Those decisions had a disproportionate effect on lower-income and nonwhite students whose family breadwinners were nurses, truck drivers and warehouse packers who by definition could not work from home.

Urban Democrats’ handling of immigration politics has also compounded tensions in their coalition. During Trump’s term, it was a point of pride among progressives to live in a sanctuary city that shielded undocumented immigrants from detention and deportation raids. The surge in migrants since 2021, however, has strained municipal resources and working-class neighbourhoods due to the pressure put on scarce housing and already-overcrowded schools.

Some on the Left insist concerns about these burdens are inherently reactionary. But for others it is a matter of public trust and effective administration. In key cities, congested streets teem with overworked “deliveristas” yoked to those very gig platforms which fail to provide a living wage; migrant mothers and children hawk snacks and cheap toys throughout parks and subways; while municipal agencies turn a blind eye to the proliferation of illegal and unsafe flats. All this has snuck up on hopeless local politicians at the same time that homelessness and evictions have spiked.

Conservatives, of course, are more than happy to pin these various challenges on misguided progressives. Yet, far from being too ambitious, Democrats’ urban governance instead reflects the extent of “policy capture” in their party. Absent a GOP fit to govern large cities, many of today’s business titans have turned to an all-too pliant Democratic Party eager to build its donor network. That relationship is unlikely to fray anytime soon, whatever one makes of the party’s episodic populism under Biden.

The truth is that if Democrats had devoted less energy to cosying up to elites and committed themselves to grand public projects and social investments in the spirit of the New Deal, fewer of their loyal supporters would be contending with extraordinary rents, mediocre jobs, underfunded transit, and underperforming schools. And a genuine record of governing “for the people” would be resonating in places which have long slipped from the party’s grasp.

One might think, therefore, that the unity displayed at the Democratic Convention is shallow and that Harris is helming a coalition susceptible to fracture. But the current state of the GOP campaign suggests Trump is no longer poised to exploit discontent in the Democratic base over their party’s contradictions and shortcomings. Nor are Republicans making the barest effort to offer a positive alternative. On the contrary, it is the Democrats who remain at once the party of government and the agents of, well, limited yet “hopeful” change.

This returns us to the regional divide which constrains the advance of a post-neoliberal order. Even if Harris wins and sticks with Biden’s flagship policies, her mandate — and thus her obligation to deliver reform — will be determined by the scale of her victory. It is certain the result will relieve elites in both parties. In fact, trench warfare between Democrats and Republicans may well revert to battles over culture, identity, and values, muffling vital issues of economic power and life chances. Until one party wages an insurgency that rallies struggling Americans of all stripes, transformational change will remain out of reach.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe