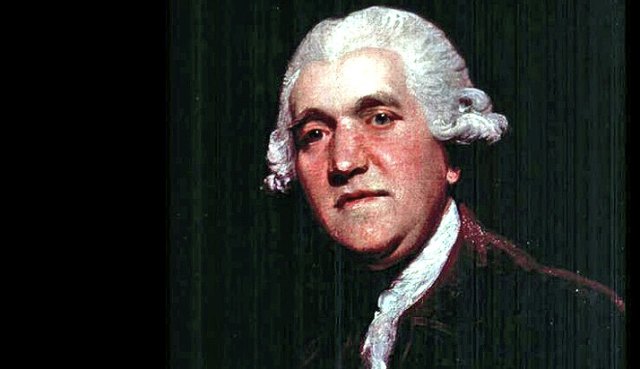

Josiah Wedgwood was Britain’s first ‘woke capitalist’.

It is an image of a black man kneeling. His hands are clasped together and chained, his neck upturned. Attached to the image are the words: “Am I not A Man and a Brother?”. Four years after this image was created, a portly doctor from the Midlands called Erasmus Darwin wrote a set of two poems entitled ‘The Botanic Garden’. In one of the poems, these lines feature in a stanza: “The Slave, in chains, on supplicating knee, / Spreads his wide arms, and lifts his eyes to Thee; / With hunger pale, with wounds and toil oppress’d, /’Are we not Brethren?’ sorrow choaks the rest”.

To describe Erasmus Darwin — the grandfather of Charles Darwin and Francis Galton — as simply a doctor would be selling him short. He was a figure the stature of Samuel Johnson. Unlike Johnson, however, he stayed in the Midlands and was transfixed by science. Darwin was a pivotal member of the Lunar Society, that constellation of thinkers who believed in the power of science to improve humanity. Coleridge, his friend and correspondent, described him as “the most original-minded man”.

He was also an abolitionist. The emancipation badge, the medallion with the inscription “Am I Not a Man and a Brother” that inspired Darwin’s verse, was made for the Society for the Abolition of the Slavery. It was the most popular symbol in the fight against the slave trade in the late eighteenth century. And it was created by Darwin’s good friend: Josiah Wedgwood.

Stoke has unfairly acquired the status of a provincial backwater. It is a Brexit city and its football team is a punchline: a foreign player can be good, but he can’t be that good if he can’t do it on a rainy night in Stoke. But Stoke’s most famous son was the emblematic figure of the long eighteenth century. Wedgwood’s work is mentioned in the novels of Austen and the letters of Gibbon. He made ceramics for Catherine the Great and the Georgian Royal Family; his family-surgeon and close friend was Erasmus Darwin; his other friends included Joseph Priestley, the minister and scientist who discovered oxygen.

Tristram Hunt, the director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, and former Labour MP for Stoke-on-Trent Central, has written a fluent and insightful biography of Wedgwood. Near the start of The Radical Potter, Hunt states: “Wedgwood’s marriage of technology and design, retail precision and manufacturing efficiency, transformed forever the production of pottery, and ushered in a mass consumer society”. But what is clear from the biography is that Wedgwood was also responding to the demands of a new consumer society.

By 1700, Britain was behind in terms of ceramic production. Japan and China were masters of exquisite design. British ceramics, by contrast, were crude. Lorenzo de Medici, the most powerful supporter of art in Renaissance Italy, loved Chinese porcelain. And so did Henry VIII. Louis XIV of France adored Chinese porcelain so much he even created a porcelain pavilion for, Hunt writes, “ceramic-themed assignations with his mistress Mme de Montespan”.

However, as Hunt notes, “over the course of the early eighteenth century, the need to substitute Asian and European imports with indigenous manufacture was vital in the development of a mass-market, consumer goods industry”. This need was satisfied by Wedgwood.

The Wedgwood family had been minor potters in North Staffordshire for two centuries before Josiah was born. What made North Staffordshire so useful was the proximity of clay and coal in the environment. Pottery ran through the veins of the family the way clay and coal veined the earth.

Wedgwood developed a leg disability from smallpox when he was 12. This meant he could never be a “thrower” — someone who operates the foot pedal on the potter’s wheel. Misfortune, was in this case, a stroke of luck. His disability allowed him to instead get stuck in on the more cerebral aspects of the business. “Design, innovation and business were aspects of the pottery trade”, Hunt writes, “to which Wedgwood could devote the attention that he could no longer apply to the thrower’s bench”.

The task of Wedgwood and his business partner Thomas Bentley was, in the words of Hunt, to “see off the attraction of luxury Chinese porcelain, dominate the fast-moving retail market, satiate the insatiable appetite of the middling sort with fashionable products sold at a healthy profit and soak up the emulative spending power of the increasingly taste-conscious Georgian consumer”.

Wedgwood came from a nonconformist religious tradition; he subscribed to political radicalism and popular democracy. His business success was nevertheless beholden to the patronage of the aristocracy. He made a creamware for Princess Charlotte, the wife of King George III “who set the fashion in London”. Hunt emphasises this ideological fissure when he notes that “a luxury product endorsed by high society was thus by far the most effective means for developing a profitable, mass-market commodity and if Thomas Bentley and Josiah Wedgwood were to secure the patronage of the trend-setting nobility they had to jettison their political radicalism, Nonconformist ethos and thirst for democracy”. The fissure, however, would be more brutally exposed by Wedgwood’s entanglement with the trans-atlantic slave trade.

The demand for ceramics was linked to a demand for other goods in the eighteenth century; porcelain was a pretty appendage to drink and grub. In particular, the period witnessed a tea craze. Tea was imported by the East India Company from China. The Company also imported sugar from slave plantations in the Caribbean. Sugar went from being a luxury product to a “dietary staple”. It was used to make chocolate, jam and treacle. But most importantly it was used to drink tea. 8,000 tons of sugar were imported to Britain in 1663; it was 97,000 by 1775. Britain had developed a sweet tooth.

But it was a sweet tooth that encouraged an industry characterised by savage cruelty. As Adam Hochschild makes clear in his book Bury the Chains: “When slavery ended in the United States, less than half a million slaves imported over the centuries had grown to a population of nearly four million. When it ended in the British West Indies, total slave imports of well over two million left a surviving slave population of only about 670,000”. Wedgwood was complicit in this industry: he exported pottery to slave plantation estates in Barbados and Jamaica. And he personally took commissions from slave-owners. But by the 1780s, he was passionately opposed to the slave trade.

The committee for the abolition of the slave trade was founded in 1787 by William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and Granville Sharp: the Three Musketeers of British Anti-Slavery activism (With Olaudah Equiano as d’Artagnan). Wedgwood was subsequently elected to the committee. During this period, he “wrote impassioned letters, circulated petitions, attended meetings and joined boycotts”.

He also created the emancipation medallion, which was, as Hunt notes, “the dominant motif of anti-slavery activism until illustrations from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin became prominent in the nineteenth century.

Wedgwood was, so it seems, a bundle of contradictions. Much of his working life was spent trying to negotiate his desire for business success with his concern for social justice. Eric Williams, the Trinidadian statesman and historian, famously argued that the British ended the slave trade for financial rather than moral reasons. For Williams, this is an indictment of Britain. Many people today — on the Left and Right — denounce corporations and businesses who ostentatiously display support for social justice movements. The phrase ‘virtue signalling’ is typically used as an insult.

Although many critics denounce social justice warriors and woke capitalists as sanctimonious, the underlying criticism of them is that they are insufficiently moral; that they are engaging in activism to sell something or gratify their vanity or be in with the Cool Kids. They are not doing it simply because it is the right thing to do.

But what is clear from Hunt’s biography of Wedgwood is that the Staffordshire potter used our materialism and desire to emulate high-status people to advance the abolitionist movement. The materialism and trend-setting craze that fuelled the slave trade — the desire for sweetened tea and sumptuous ceramics to adorn them — also undermined it: this time by seeing respectable people wearing a beautifully-crafted medallion. As Hunt writes: “Even though the consumer revolution of the eighteenth century had helped to fuel the Atlantic slave trade, Wedgwood’s understanding of its ethos of emulation now enabled him to popularise abolitionism more effectively than any number of Sharp petitions or Equiano readings”.

Social movements, political ideologies and religions don’t spread because we individually analyse beliefs and say This is Obviously Good and This is Obviously Bad. We are sociable creatures: we care about what our peers do and the behaviour of charismatic people. This isn’t a normative judgement; it is a descriptive fact. Rather than bemoaning virtue signalling and woke capitalism, we ought to understand how we actually behave. The spread of an ideological movement through material interests is not necessarily a bad thing.

Which is not to say it’s necessarily good either. The moral focus should be on the beliefs themselves, rather than how they are spread. I am critical of many contemporary vogueish social justice movements. However, I am critical of them because I think they are wrong and or harmful, not because many high-status people support them.

The assumption which seems to underpin the view that it is necessarily bad if moral movements are spread by non-moral means is that we are solely motivated by ethical reasoning. Any deviation from moralising therefore constitutes a betrayal of the principles we claim to espouse. But this assumption is untrue. We don’t only care about right or wrong; we also care about status.

A part of me thinks we should be more moralistic, not least because I think people who espouse an essentialist form of identity politics, and companies that jump on the bandwagon of social justice, flatten rich individual experiences. But that’s probably my religious prejudice speaking: talk of individual moral conscience only makes sense by presupposing a coherent and distinctive self. That we have a soul.

But we are also mammals. The means through which our moral norms spread will always be somewhat imperfect, haphazard, bungling; reflecting the vagaries of status. Charles Darwin’s paternal grandfather was Erasmus Darwin. His maternal grandfather was Josiah Wedgwood.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe