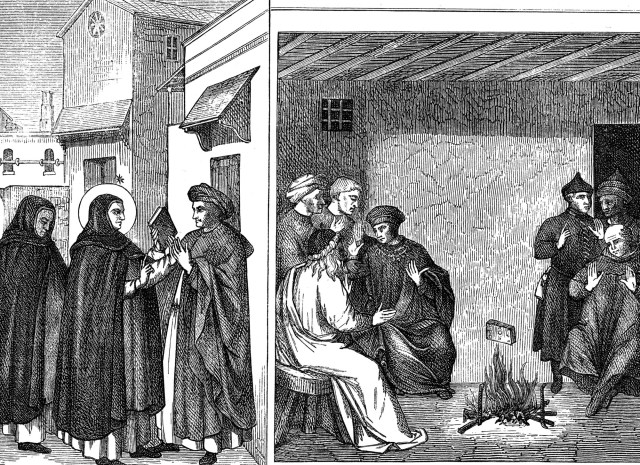

Science provided a useful bulwark against heretics like the Cathars, shown in this engraving. Credit: Ann Ronan/Getty

In late 1327, outside the Church of Santa Croce in Florence, the poet and astrologer Cecco D’Ascoli was burnt at the stake. Cecco had, until three years previously, worked at the University of Bologna where he taught students about the stars — his lectures are preserved in a commentary he wrote on the foremost astronomy textbook of the day. For those seeking examples of the medieval Church treating practitioners of science as heretics fit only for the pyre, he is an outstanding case.

Look more closely, though, and Cecco’s scientific credentials start to unravel. Although nothing excuses the inquisitors who sent him to his terrible death, it is important to understand why they acted as they did. It turns out that Cecco was teaching demonology to his students at Bologna: his lectures were full of references to binding immaterial beings.

Even more damning, according to an inquisitor, he cast the horoscope for Jesus of Nazareth, noting that the Messiah’s poverty and suffering were written in the stars. To assert that God himself was subject to astrological influences sounds like an unforgivable heresy, but in fact Cecco was forgiven. Stripped of his lectureship and heavily fined, he nonetheless escaped with his life. Only after a second offence, in Florence a couple of years later, was the full force of the law brought to bear.

Cecco owes his fame entirely to his execution, which enabled 19th-century historians to laud him as a martyr for science. However, not only was he more magician than scientist, the manner of his death is unique among medieval astrologers.

You will search in vain for records of scientists being arraigned by the inquisition in the Middle Ages, and even occultists like Cecco were rarely condemned until after their death. (The most notorious instances of inquisitors clashing with natural philosophers, Giordano Bruno and Galileo Galilei, date from the 1600s and even these cases are very far from straight conflicts between science and religion).

The surprising truth is that the medieval Church was generally supportive of science and mathematics. For example, it ensured these subjects were compulsory for students who wanted to graduate to the higher faculties at university, especially if they wanted to become theologians.

The universities themselves were a medieval invention. They were structured as self-governing corporations that could set their own internal rules and did not rely on royal or ecclesiastical patronage. Universities became adept at playing off secular and sacred powers against one another. When the Bishop of Paris banned the works of Aristotle in the early 13th century, the new University of Toulouse began advertising for students who wanted to study those very books.

It wasn’t long before the pope rescinded the ban and there is little evidence anyone took much notice of it anyway. Besides which, if things became intolerable a university could simply up sticks and move elsewhere. In 1209, an Oxford student murdered his mistress before making himself scarce; the townsfolk strung up his housemates in revenge, so a large group of masters and students felt it sensible to decamp to a town deep in the East Anglian marshes. Thus, was the University of Cambridge born.

The science of the Middle Ages was based on ancient Greek antecedents, especially the philosopher Aristotle, the astronomer Ptolemy and the mathematician Euclid. This legacy was seasoned with learning from the Islamic world, including commentary on Aristotle by the Andalusian Muslim Averroes and algebra using Arabic (actually Indian) numerals.

The first translation of Euclid’s Elements had been made from an Arabic version while the Latin edition of Ptolemy’s great synthesis of astronomy retained its Arabic title of Almagest. The Greek and Islamic inheritance meant that people in the Middle Ages were well aware that the earth is a sphere and even had a reasonable idea of how big it is.

The myth that the medieval papacy insisted that the world is flat appears to date from the 17th century, when Protestants used it as an example of Catholic backwardness. Indeed, our modern conception of the Middle Ages as a dark age of superstition is largely an invention of Protestant authors such as Francis Bacon and Pierre Bayle.

In reality, the Middle Ages saw technological breakthroughs such as spectacles and the mechanical clock, as well as the adaptation of eastern inventions like paper, the compass, gunpowder and printing. Far from being a closed society, medieval Europe welcomed outside influences and did its best to improve on them.

In the field of theoretical science, many of the most notable developments took place at the universities. The thousands of students attending Oxford, Cambridge, Paris, Cologne, Bologna and elsewhere needed teachers, and their fees provided a steady income for those wanting to devote their lives to science or mathematics.

The result was a flowering of scientific speculation in the fourteenth century that challenged the dominance of Aristotle. For instance, at Merton College, Oxford, a group of scholars developed mathematical techniques to describe moving objects. The earliest of their number, Thomas Bradwardine, who went on to become the Archbishop of Canterbury, derived a formula that enabled him to calculate the speed of a body in accordance with the theories of Aristotle.

The formula is wrong because Aristotle’s mechanics is also in error, but the use of an algebraic function to describe the physical world was a novel idea. Other Merton mathematicians discovered a means of calculating the distance travelled by a uniformly accelerating object. This formula was later adopted by Galileo, without attribution, as a core part of his own work on falling bodies.

Meanwhile, Jean Buridan, rector at the University of Paris, set out to show that it is not physically possible to show that the earth is rotating. In other words, from our standpoint, we can’t tell whether the globe is moving or the heavens are turning around us.

He compared the situation to a boat floating along a calm river. When observing a stationary vessel, it isn’t possible for a passenger on the boat to tell whether he is moving or the other vessel is. We are all familiar with a similar experience when on board a train that has stopped at the station, next to another train that is leaving. Buridan’s arguments about relative motion were later used (again, without attribution) by Nicolas Copernicus to explain why we cannot directly detect the earth orbiting the sun.

Buridan also developed the concept of impetus and showed that, in the absence of friction, once an object has been set in motion, it should keep going forever. This was true of the planets, he thought, which should continue their orbits around the earth for eternity once God had given them the requisite shove at the moment of creation. Buridan’s theory of impetus, which anticipated Isaac Newton’s First Law, challenged Aristotle’s dictum that all moving objects need something else to move them.

The Church looked upon this work benignly. Mathematics was considered good training for young minds that needed to be raised from mere ephemeral concerns before they were fit to contemplate divine truths. Science was valuable because medieval people thought of the world as God’s handiwork. To study it was a way of glorifying its creator.

A useful metaphor, picked up by Galileo, was to speak of God having written two books — the Bible and nature. As they both had the same author, they could not conflict and the Church had nothing to fear from science properly practised.

Science also provided a useful bulwark against heresy. The most feared sect of medieval heretics, the Cathars of southern France, claimed that the material world was the work of the devil. The Church encouraged its missionaries to use the wonders of nature as proof that the universe was created by God and that the Cathars were mistaken to dismiss it as evil.

Premodern science always served an agenda, and things were no different in the Middle Ages. No one was pursuing the disinterested study of nature; even Jean Buridan, when noting that the planets needed nothing except an initial impetus from God to keep them moving, sought to dismiss the spirits with which the likes of Cecco D’Ascoli populated the sky. By disenchanting the world, science reinforced monotheism.

Historians of science compare the role of medieval natural philosophy to that of a handmaiden, serving theology. Despite the subservient position, this afforded scientific practitioners a degree of protection and allowed them to advance theories that turned out to be essential to the work of famous figures like Copernicus, Galileo and Newton in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Far from being cowed by the Church, medieval natural philosophers could explore new concepts that, perhaps unintentionally, laid the foundations of modern science.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe