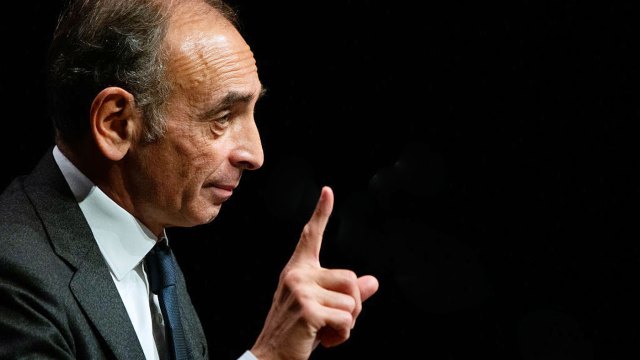

Zemmour flits easily from truth to untruth (Credit: Benjamin Girette/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

I have a problem with Éric Zemmour. He has the most astounding gall, like a character from a Balzac novel. The books which have made him famous are stuffed with sweeping judgements and cutting assertions. He has a knack for pithy one-liners and has mastered today’s art of being harsh and simplistic. He does not know nuance. He flits easily from truth to untruth, with a clear predisposition towards exaggeration and downright falsity. Ever-ready to illustrate what he is saying with examples, he is not, to put it mildly, meticulous in the way he uses them. You feel an urge to pastiche his writing, so peppered is it with historical references, some appropriate and some not.

He likes to quote from two of my books. One follows the unusual fate of Dreyfus supporters who lived long enough to experience the Second World War and the Nazi occupation of France. The second book attempts to understand why so many former “anti-racist” activists from the Left and the far-Left became collaborators and why so many former anti-Semites of the Right and the far-Right took part in the Résistance. Sometimes, Zemmour quotes me accurately. Often, he adds his own selective emphasis to my work and attributes interpretations to me which are his and not mine. On occasion, he will start a sentence with “as historian Simon Epstein says,” before wheeling out a misrepresentation of something I have written or, worse, something I have not written at all.

I haven’t registered my disapproval before. Firstly because I didn’t really care enough. Zemmour, who I didn’t think was such a bad egg, was not alone in using and abusing history for his own ends: this has been part and parcel of intellectual life, and especially of the polemic-obsessed media, for some time. I also used to find it funny — really funny — to see this old Gallo-Roman country, the Church’s eldest daughter, rely on a Jew to fulfil the threefold mission of eulogising France’s lost greatness, bemoaning its besmirched identity, and proudly raising its old standard once more. At times, it felt Zemmour was the new Joan of Arc. It was he who was holding the sword others had dropped and rallying the troops for battle.

I do not know what mark the man will leave on France’s history. Will it be providential or tragic? Or — and this cannot be ruled out — fleeting and benign? Or perhaps even comical? But that is not why I am writing. What I am interested in here is the position he will occupy — and doubtless already does occupy — in the long and tormented history of the Jews of this country. France’s Jews, like the rest of the diaspora, know they are exposed to anti-Semitism, an intractable problem which alternates between phases of remission, sometimes short and sometimes long, phases of acceleration, flare-ups, and then further remission. Jews also know that some among them — a minority thankfully — cave under pressure and accept anti-Semitism. In some cases, they even help to propagate it.

It used to be the far-Left that best illustrated this problem. In the winter of 1953, Jewish communists in the Soviet Union competed with one another to lend credibility to dark conspiracy theories about Jewish doctors. More recently, Left-wing apologists of Islamism have included Jews, who profess a radical hatred for the State of Israel and the Jewish people. These anti-Zionist Jews try to make themselves useful by mildly scolding their fellow activists — who profess to be humanitarians — for chanting “Death to Jews!” at pro-Palestine demonstrations. They explain, gently, that some demands are best kept to oneself, and that these especially should not be uttered in public — for obvious tactical reasons.

What’s different with Zemmour is that he is on the far-Right and not on the far-Left. He is akin to Trump-supporting ideologues in the US and their Hungarian counterparts and is, in France, at the forefront of this new way of doing politics. His spin on Dreyfus (who, in his eyes, wasn’t really innocent) has a rotten smell. His apology for Pétain (who, in his eyes, wasn’t guilty really) puts him firmly in the camp of the post-Vichy far-Right. It also positions him on the edge of the neo-Nazi, ultra-far-Right (only the edge, of course; as a Jew, he will never quite belong). The same goes for his opposition to the Pleven and Gayssot laws, without which racism, anti-Semitism and Holocaust denial would be permissible. And then there were his comments about the Jewish children who were buried in Israel after being brutally killed in Toulouse, which were truly despicable.

When Zemmour castigates women, immigrants, homosexuals, socialists, centrists, elites, or metropolitan liberals, he does it out of profound conviction, fascinated as he is with the rhetorical heritage of the far-Right — which he has himself expanded, copiously, with his rants.

Media savviness, too, motivates his skewering of Jews. His historical mission, as he sees it, is to reconcile the patriotic bourgeoisie and the working classes. In concrete terms, this means that he is betting simultaneously — and this is difficult — on both traditional Right-wing voters and supporters of the populist far-Right. The fact that he is Jewish reassures the former group (“he can’t be a fascist so we can vote for him!”) The fact that he maligns Jews despite being one himself entices the latter (“there’s no way he’ll be bought off, we can trust him!”).

The former bunch appreciate his harking back to author Charles Péguy and his admiration for De Gaulle. The latter like his scorn for Zola and his rehabilitation of Pétain. His unconcealed Jewish roots help him plot out a march on Paris which, in a complete ideological mish-mash, passes through both London and Vichy.

If the trend revealed by recent polls is confirmed — in other words, if he manages to definitively capture the two groups of voters he needs to remain a contender — and if he also manages to recruit non-voters by using his swagger to pull them out of their apathy, he will have a supply of votes perfectly sufficient to shake up the 2022 presidential election. Given certain conditions, and with a little luck, he would be in a position to do what both Le Pens failed to do, namely to seduce republican voters without alienating anti-republican voters, and vice-versa. He would be in a position to shatter — or at least crack — the “glass ceiling” which has kept the far-Right out of power for so long. He would achieve this thanks to his patter, his strategic know-how and his stubbornness. But it would also be in part thanks to his Jewishness, which makes it impossible to call him a Nazi or a fascist. It gives him more leeway on everything controversial.

Unlike Henry IV, the French Renaissance King who was born a Protestant, Zemmour won’t have to reason that “Paris is well worth a mass.” Historically, he is perhaps in the tradition of Arthur Meyer, the editor of the Gaulois newspaper, who converted to Catholicism in 1901. He also borrows from Edmond Bloch, who rubbed shoulders with the French far-Right in the 1930s and also ended up converting to Catholicism. But Zemmour, who aspires to lasting renown where these two predecessors enjoyed only passing notoriety, will not have to follow them to the font. Far from being a hindrance to his irresistible rise, his Jewishness is his trump card. Let’s be frank: this is both masterful and unprecedented. As a political observer, I find it fascinating. As a Jew, I must admit I find it disgusting.

This essay appears with the permission of DDV, the journal of the International League against Anti-Semitism, where it was originally published.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe