Small acts of resistance. Credit: Ivan Romano/Getty

In the uneasy, bright days of the first lockdown of 2020, my father remembered 1946, and his own father setting off on the train from Wallingford to London to debrief Admiral Dönitz, Hitler’s successor for the last days of the Reich.

I was impressed. I knew Henry was in Naval Intelligence, but not at this level. Was my grandad M, then?

‘Well,” said my father, “Not M. A few letters back from that. Maybe H. He could speak German, was the point.”

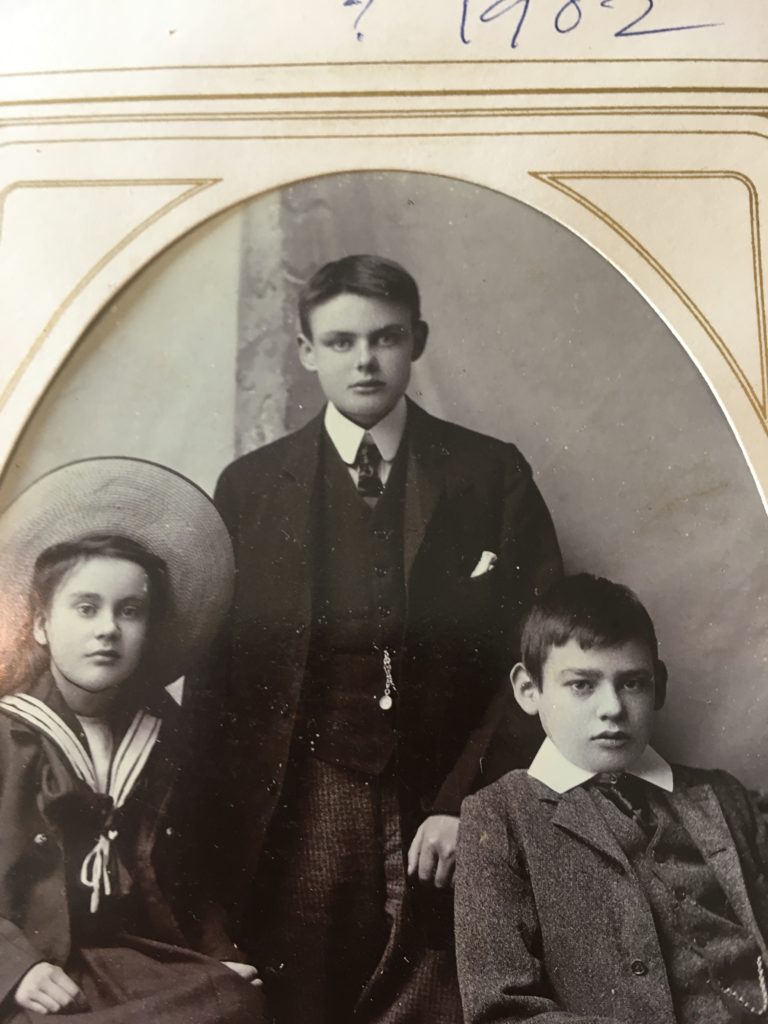

Henry Clanchy loved languages. We have his Russian vocabulary words, still, written in fountain pen, tucked in a silver cigarette case. He might have been happier as an academic, like his son, Michael, but he was sent to sea at the age of 12 instead and was sea sick on every boat — even the ones he commanded.

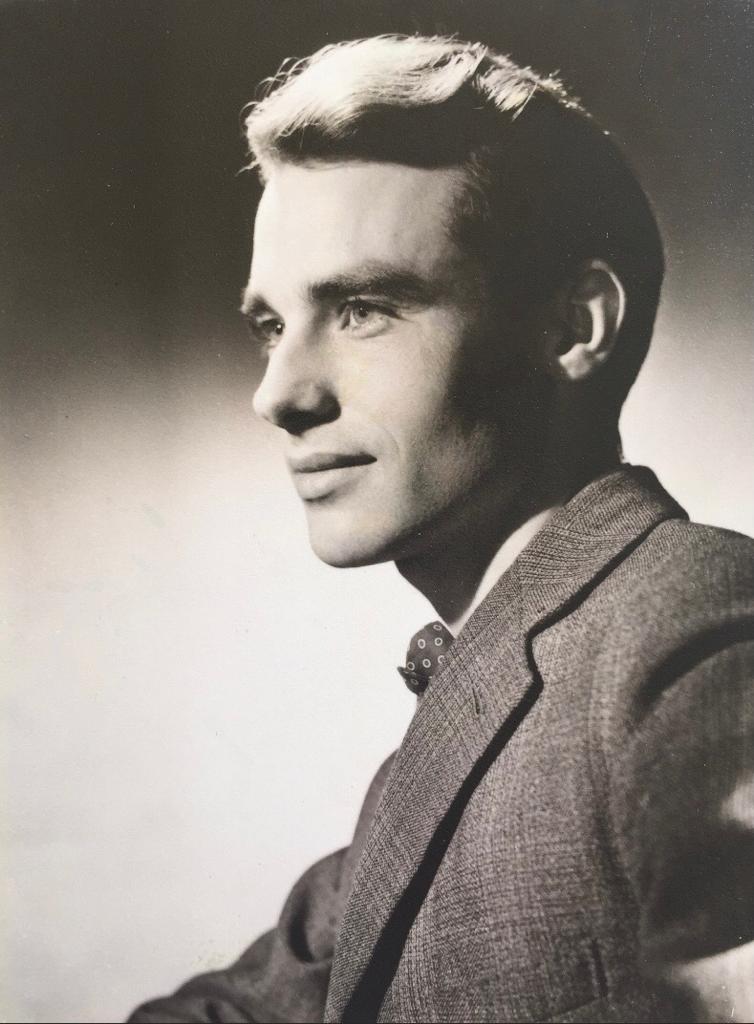

These memories didn’t come just because my father was 83 and in the last year of his life. Lockdown, with its apocalyptic quiet, its empty streets and filmic light, returned him to foundational experiences of authority and fear. My father’s first years were passed in Stalinist Moscow where Henry was Naval Attaché. He returned to England only in 1939, on the last train across Europe, an experience of terror which resisted 40 years of therapy. Then, just under six years old, and speaking Russian and German in preference to English — he’d had a German nanny — he was sent to a brutal, chaotic prep school. A Catholic version of Ronald Searle’s St Custard’s, or a ‘School’ in Decline and Fall, a place where the boys would sell poached rabbits and kindling to the hungry junior masters.

My father’s deepest feelings were set against authority. His refusal to sit on any sort of high table had cost him all his life. Now, when orders were being given from a single desk in Downing Street and the press talked in hyperbole and numbers, when the careful, fragile threads of his web of social contacts — the Norman French Seminar, the vegetarian café, his grandchildren — were all cut at once; when friends in nursing homes arbitrarily found themselves in confinement more solitary and hopeless than would be handed to any prisoner, his jaw set again. “Obviously,” he said, squinting up at me — a dystonia had recently collapsed the nerves and muscles of his neck — “Obviously, what you do in these circumstances is look around and see who else is not going to fall in with it. Who is your friend?”

By “fall in with it” he meant: performatively join in any rituals of shunning, add to the tangible fear. As a personal protest, he insisted on continuing to walk each day to the mini-market to collect the Guardian, leaning on a stick, chin to chest like a condemned prisoner, saying good morning to each person who stepped wide of him. More than once, he was asked by a self-appointed commissar, or train guard, or Grabber the school prefect, where he lived, and why he was out of his own street, and he would explain he wasn’t shielding, he was still allowed to walk about. He took comfort in going in to the whole food shop where the hippy owner remained disbelieving and merry, greeting him warmly as she raised the price of chana dal yet another notch.

Mostly, though. I was his friend. He’d trained me well. I walked round the corner to see my parents every day of lockdown, even before it was clear this was permitted. They weren’t well enough to be on their own: they had between them two sorts of cancer, lupus, depression, osteoporosis, shingles, heart damage, nerve damage, and recurrent cellulitis. They couldn’t reach their own bulb sockets, high shelves, weeds, and feet.

They needed help too with the NHS. Help with the late letters, the contradictory emails, the cancelled dates, the disappearing consultants, the tangled medications, the finding out if you had to go private, who you paid, for how long, under which name, when, help with the whole vast behemoth of the thing. It had dominated our lives for several years already, and it didn’t seem so unexpected somehow that it had become our national Authority, our religion, a thing we sang to and clapped.

It’s not that my parents weren’t grateful to the NHS or the extra years of life it had brought them: they were. But under pressure, first austerity and now lockdown, they had seen it drift into an ever more attenuated, disparate, emergency-orientated system. With Covid, the imperative to save lives, through high-tech medical measures, especially the lives of elderly frail people like them, intensified, while the means of delivering simple, limited medical care, such as podiatry and physiotherapy, withered away. This, though, was the reverse of my parents wishes. They had each had more than their fill of hospitals. They had sore backs and feet. They wanted no more drastic interventions. If their conditions couldn’t be humanely managed, they wanted to die at home.

Over lockdown, my father was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease, entirely over the phone. He never met a nurse or received physiotherapy. In order to change his drug regime he had to come off his antidepressants: a terrifying step when the Parkinson’s locked his mood, made his depression unshiftable. But no new prescription was forthcoming. Each day, after I’d reached something down from a shelf or photographed a wound, we would supplicate another doctor. Eventually, we were told the consultant had gone on holiday and forgotten the prescription. I walked my shaking father round the water meadow and he remembered his father.

“Henry,” said my dad, “was very upset when he got to the prison cell to find Dönitz’s uniform and personal things had been taken away. In particular, his watch was missing. The guard had taken it.”

“Now Dönitz,” said my father, picking up his pace a little, “was a terrible man. It was ridiculous the way he was treated as a sort of gent. He was a fascist like the rest of them.” My father was a scholar, among other things, of Henry III and Simon de Montfort. He taught me about the English pogroms before I was 10, taught me about the evils of blood libels, the lie of Hugh of Lincoln, and to never, never think that England was more free of anti-Semitism than any other place in Europe.

Nevertheless, Dönitz was the same age as Henry. He was also a Catholic, also a boy who had been sent to sea and buffeted by war. He had been a British POW when Henry was fighting the White Russians. There are lonelinesses which speak to other lonelinesses in the shadow of authority. There are human gestures which benefit the giver as much as the recipient.

“And the next day,” said my father, “the next day, when he came home, he got Dönitz’s watch back. He was pleased about that.” And he raised his head, with difficulty, to smile at me. My father, I am sure, associated the gesture with his German psychiatrist, who always replied to letters by return, who was soon to get hold of Neurology and shake the prescription out of them.

My parents surely had more, and more detailed, Advanced Decision documents about their future medical treatment and death than any other pensioners in Britain. I had a drawer full of copies. They had carefully prepared folders to take to hospital with them, documents to offer the authority at the border. But, as I have written elsewhere, for my mother, this did not work. On a first hospital stay, one set of advanced decisions went missing. On her final journey, she did not have them at all, as she was supposed to be going for a day visit.

In January, 2021, under peak Covid Authority rules, alone without documents or an advocate, everything happened she had specified against: a drastic operation, intensive care and a ventilator. “It is as if,” said my father, as we sat despairing at the kitchen table, “she had been kidnapped.” In hospital, she contracted Covid-19. Track and Trace phoned the house repeatedly, lending a Stalinist note to proceedings as they demanded to speak to my mother. We were permitted one end of life visit, during which my father also contracted Covid-19. Ten days later, after repeatedly pulling feeding tubes from her own throat, my mother died, entirely alone.

Covid and grief weakened my father’s heart. Two days after my mother’s death, I had to pick up my father’s advance directive and follow its very clear instructions: if he suffered a stroke or heart attack, he wanted to die at home. I had to be grimly determined. First, I denied, like Judas, an ambulance three times. I took surreal calls from the council, explaining that I was entitled to help with care, but as there were no carers, none would be coming. Track and Trace called again, asking for my mother.

But help came. My cousin, whose father had been to prep school with my father, and had inherited his anti-authoritarian streak, crossed the country to be by my side. My brother was always present. With that, I remember the humanity of the medical people who came: the district nurse, the GP, and the teams who arrived in the night with morphine and tranquillisers. Each one of them affirmed my father’s wishes and enabled them, and said, very often, that a death at home was what they wanted for themselves, what they wanted for their relatives. I remember a nurse at 3am pulling the visor off her sweating face and saying, with the vehemence of a secret, of information passed under the castle walls, ‘This is the right thing to do. This is what everyone wants for the people they love.”

I loved my father and my mother very much. A year later, I am haunted by the loneliness of my mother’s death and comforted by the intimacy and peace of my father’s. I wonder if those deeply humane doctors and nurses — and the equally humane, I am sure, doctors and nurses who cared for my mother — are more or less able, now, to allow people like my parents to choose to die out of hospital and die without intervention. Over Covid, the numbers dying at home have leapt by 39% , but this remains little spoken of, as if each of those deaths were an accident or secret, a subversive happening under the shadow of authority, a watch taken back from a guard. But each one is a just a small, human exchange, and the walls of this authority are made only of ourselves.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe