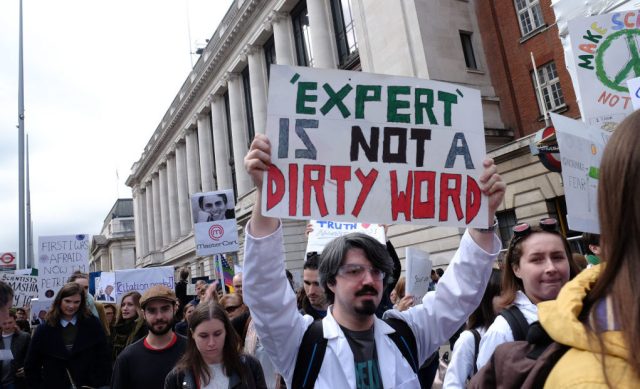

Do his findings replicate? Photo by Jay Shaw Baker/NurPhoto via Getty Images

With the rise of so-called populist movements across the globe and the loss of common sources of information in favour of partisan news outlets and conspiracist websites, the past few years have been characterised by a breakdown of socially authoritative knowledge.

The people, some commentators caterwaul in dismay, just don’t trust the experts anymore. But an essential part of this story is that the experts have to a significant extent lost trust in each other and in their institutions. This shift came, in large part, due to the replication crisis in science.

In 2010 Dana Carney, Amy Cuddy and Andy Yap wrote a paper in the academic journal Psychological Science detailing a finding about a certain kind of “powerful” pose — most iconically, one in which the poser has their hands on their hips and their legs spread apart. The authors, based on a study with 42 participants, asserted that “minimal posture changes” could “over time and in aggregate… potentially… improve a person’s general health and well-being.”

They went on to say: “This potential benefit is particularly important when considering people who are or who feel chronically powerless because of lack of resources, low hierarchical rank in an organization, or membership in a low-power social group.” In 2012, Cuddy gave a popular TED Talk called “Your Body Language May Shape Who You Are,” and in 2015 she published a self-help book called Presence: Bringing Your Boldest Self to Your Biggest Challenges.

It was a New York Times best-seller, but right around the same time her psychologist colleagues were starting to try, and fail, to “replicate” her findings — to redo her experiments and achieve similar results. They could not find independent evidence of the effect she had become rich and famous for trumpeting.

Power posing was like catnip for a lot of people, and it’s symptomatic in many ways of the problems with public engagement by experts in social psychology. First, it suggests that humans and our social world are highly malleable, our identities susceptible to massive alterations as consequences of tiny, simple interventions. There’s no particular a priori reason to think that these interventions will have the claimed effects: no first principles, no overarching theory. Second, it presents a kind of feel-good solution to problems of a vulnerable group: here, the homogenised “chronically powerless.” Third, while it originated within the scientific community, it made its way to the public consciousness at least in part through being commodified for an audience that was only superficially scientifically literate — the TED Talk crowd.

The replication crisis is an ongoing event across the sciences involving the failure of published and often celebrated results to replicate in subsequent experiments. It is the most important science story of our times and the subject of psychologist Stuart Ritchie’s new book Science Fictions.

Ritchie tells the story very well; the achievement of the book as a work of popular science comes from the way it switches smoothly back and forth among three tasks, all of which it performs with considerable success.

First, it gives the unfamiliar reader an overview of the details of professional science — grants, journals, peer review, that kind of stuff. Second, it develops evocative and engaging narratives, sometimes funny, sometimes shocking, of specific instances of scientific misconduct and error. Third, it delves into quite technical material about statistics and experimentation, covering problematic research practices like p-hacking and potential stopgaps and solutions like specification-curve analysis.

Ritchie focuses on psychology, his area of expertise and the field most prominently hit by the replication crisis. Recent papers seemingly established things like “college students having psychic powers” (Ritchie was personally involved with the unsuccessful attempt to replicate that paper) and “messier or dirtier environments cause a rise in prejudice and stereotyping” (the author of that paper turned out to have wholly fabricated the data).

As these results started being discredited, classic results came under scrutiny too. The Stanford Prison Experiment of Philip Zimbardo, which found students assigned to be “guards” in a week-long simulation abusing students assigned to be “prisoners,” has been famously used to suggest the near-universality of human cruelty; and the “priming” studies, in which tiny, unconscious suggestions can lead participants to behave in very different ways, were taken by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman to “threaten our self-image as conscious and autonomous authors of our judgments and our choices”. A meta-replication in 2015 found that of 100 chosen studies from three psychology journals, only 39% of experimental results replicated.

Other such studies found rates of 62%, 77%, 54% and 38%. Not good numbers! And Ritchie notes that similar meta-replications have produced worrying results in economics, neuroscience, evolutionary biology, marine biology and organic chemistry, and, perhaps most worryingly, medicine. In some cases, studies fail not replication but “reproduction” — other researchers analyse the data set actually obtained in the original study and come to different conclusions due to errors, unspoken assumptions or unjustified analytic decisions.

Ritchie begins his book with a humorous overview of the scientific process. His goal is to show that this process is ineluctably social, and he does this convincingly. Scientists must justify their work to other scientists, both in terms of its importance and in terms of its accuracy, and scientists must check other scientists’ work. When one scientist publishes a result, if that result is true, another scientist should, barring chance deviations, be able to replicate it in their own lab. If such a replication cannot be done, the result means much less, because it now describes not how the world is in general, but at best how one scientist’s experiment went.

Why might a published result fail to replicate — that is, why might an academic journal publish a result that’s ultimately false? Ritchie mentions four underlying causes: fraud, bias, negligence and hype. Fraud can be objectively very obvious while still escaping notice, as in studies which use the same image for purportedly different situations. And scientific institutions often fail to hold fraudulent scientists to account when those scientists are prestigious, due to both gullibility and self-interest.

“Bias” includes various kinds of political biases and identity-based stereotypes, but Ritchie stresses that biases in favor of intellectual novelty and impact are if anything more significant in the current scientific landscape, including the well-known bias against publishing negative results — that is, against publishing papers that tell us only that something exciting did not happen.

Ritchie’s section on bias also includes a clear account of some technical elements of statistical reasoning, failures to adhere to which are Ritchie classes as “analytic biases.” These biases include things like only reporting a portion of collected data, excluding certain data points for arbitrary reasons, and deciding whether or not to continue looking for data based on initial results. These biases can in fact creep into a scientist’s work rather innocently, based merely on their conviction that their hypothesis is correct — the “bias” in question.

Surveys found that 65%, 40% and 57% of psychologists respectively had engaged in those three practices. The section on negligence also includes some great descriptions of statistical techniques and instruments that have been developed to detect various kinds of scientific error, and the section hype mentions NASA’s claim, later debunked, to have found arsenic-based life on Earth, as well as the “growth mindset” fad, the “probiotics” fad, and the ever-changing directives of nutritional science.

Serious though this is, there is also something more specifically pernicious about the replication crisis in psychology. We saw that the bias in psychological research is in favour of publishing exciting results. An exciting result in psychology is one that tells us that something has a large effect on people’s behavior. And the things that the studies that have failed to replicate have found to have large effects on people’s behavior are not necessarily things that ought to affect people’s behaviour, were those people rational. Think of the studies I mentioned above: a mess makes people more prejudiced; a random assignment of roles makes people sadistic; a list of words makes people walk at a different speed; a strange pose makes people more confident. And so on.

All of these studies involve odd effects from environmental cues. Taken together, they suggest an image of human behaviour which is highly irrational and highly manipulable. This is, in fact, the image of human behaviour which I think a great many educated people hold at the moment.

Of course, the existence of the replication crisis does not by itself mean that this image is the wrong one. But as these overhyped and ultimately flawed studies have made their way through the press releases and TED Talks Ritchie discusses into the broader consciousness of a certain class, I think they’ve helped persuade that class that that image is indeed the right one. As we reevaluate our scientific institutions, it may pay to reevaluate this image as well, and its influence on our social organisation more broadly.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe