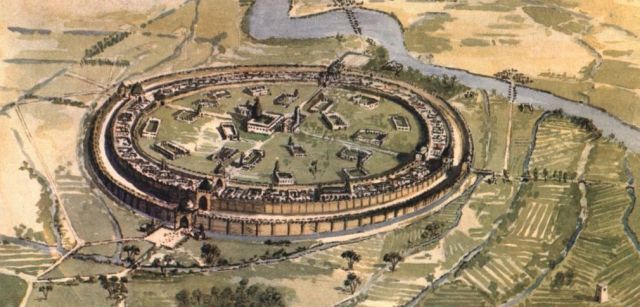

Baghdad in the time of Mansur. Painting by Edmund Sandars. From “The Caliphs’ Last Heritage, a short history of the Turkish Empire”, 1915 Photo: Getty

Happy Birthday, Baghdad. Today you are 1,258 (a figure we’ll return to later). In the midsummer furnace of 30 July 762, a date considered auspicious by the royal astrologers, the Abbasid caliph Al Mansur, supreme leader of the Islamic world, offered up a prayer to Allah and laid the first ceremonial brick of his new capital on the Tigris river. “Now, with the blessings of God, build on!” he ordered the assembled workers.

And build on they did. It took them four back-breaking years, slogging away in the fiercest summer temperatures of Iraq, to complete the job, and by 766, it was done. Mansur’s city was an architectural marvel from the start. “They say that no other round city is known in all the regions of the world,” wrote Al Khatib al Baghdadi, the eleventh-century author of the comprehensive History of Baghdad.

Four straight roads ran from four gates in the outer walls towards the city centre, past vaulted arcades containing the merchants’ shops and bazaars, past squares and houses. At the heart of the circular city was a vast royal precinct almost 2,000 metres in diameter, empty apart from two monumental buildings. The Great Mosque stood alongside the caliph’s Golden Gate Palace, a classically Islamic expression of the union between temporal and spiritual authority.

Built on the west bank of the Tigris, the imperial capital spread swiftly to the east, where it grew at breakneck pace. The famous Barmakid family, well-heeled viziers to the Abbasid caliphs, spent 20 million silver dirhams building an opulent palace there, and another 20 million furnishing it (to put that in perspective, a master-builder working on the construction of Baghdad was paid 1/24th of a dirham a day).

Wisely, in an age when men could lose their heads with a caliph’s nod to the ever-present executioner, it was presented as a gift to Al Mamun, son and heir of the great caliph Harun al Rashid, and became his official residence in the early ninth century, glittering centrepiece of the Dar al Khilafat, the caliphal complex that was home to future generations of Commanders of the Faithful.

All this was mightily impressive, but very quickly the architectural pre-eminence of the Round City became the least of Baghdad’s merits. Flush with money, the capital presided over a cultural revolution every bit as remarkable as its burgeoning political, military and economic power. Poets and prose writers, scientists and mathematicians, musicians and physicians, historians, legalists and lexicographers, theologians, philosophers and astronomers, even cookery writers, together made this a golden age, Islam’s answer to Greece in the fifth century BC.

To put it in perspective, more scientific discoveries were achieved in Baghdad during the ninth and tenth centuries than in any previous period of history. Never mind its meteoric rise to the cultural zenith of the Islamic world, within a century of its construction the city was the intellectual capital of the planet.

“Seek knowledge even to China,” the Prophet Mohammed had urged his followers and the greatest minds in the Muslim world flocked to Baghdad in their droves to do so. Their movement across continents to seek knowledge — as well as fortunes — was scarcely less extraordinary than the world-changing Arab conquests of the seventh century. Hardly surprising, then, that the geographer Al Muqaddasi should call Iraq “the fountainhead of scholars”.

Ninth-century Baghdad emerged as the scientific powerhouse of the world. The celebrated Bait al Hikma, the House of Wisdom, became the nerve centre of Abbasid intellectual activity, part-lavishly endowed royal archive, part-learned academy, library and translation bureau, with a staff of scholars, copyists and bookbinders. By the middle of the century, it was the world’s largest repository of books, the seed from which the golden era of Arabic science flourished.

There were pioneering scholars like Mohammed ibn Musa al Khwarizmi, a master of arithmetic and astronomy whose ground-breaking work Al Kitab al Mukhtasar fi Hisab al Jabr wal Mukabala (The Compendium on Calculation by Restoring and Balancing) bequeathed the world the dread term algebra, scourge of children’s schooldays for more than a thousand years to come.

His Book of Addition and Subtraction According to the Hindu Calculation introduced for the first time the decimal system of nine numerals and a zero. Within a century it led to the discovery of decimal fractions, which were then used to calculate the roots of numbers and calculate the value of pi to sixteen decimal places. Those of us who never want to see quadratic and linear equations again can remember Khwarizmi instead in the word “algorithm“.

The caliph Mamun wanted to test the accuracy of the ancients’ measurement of the world’s circumference and commissioned the Banu Musa brothers to investigate. They were a prodigiously wealthy family of astronomers, astrologers, engineers and experts in geometry who founded the Khizanat al Hikma, Treasury of Wisdom, a library-cum-hostel for scholars. Their experiments hammering in pegs on cords across the plain of Sinjar, north-west of Baghdad, concluded that the ancients had got it right, and the circumference of the world was indeed 24,000 miles (not bad, the precise figure is 24,902 miles).

Mamun, royal emblem of the outward-looking, intellectually inquisitive spirit of the time, also commissioned his famous world map in which the Atlantic and Indian oceans became open bodies of water, rather than Ptolemy’s landlocked seas, and in which the Mediterranean was far more accurately measured.

Great minds roved freely in Abbasid Baghdad. In the field of medicine Nestorian Christians and their Muslim descendants led the way, none more brilliant than Hunayn ibn Ishak, head translator in the House of Wisdom and chief doctor to the ninth-century caliph Mutawakil. By the age of 17 he had translated On the Natural Faculties, one of many titles by the second-century Greco-Roman physician Galen, whose scientific theories dominated European medicine for 1,500 years.

Hunayn was a distinguished scientist and author in his own right. His Ten Treatises on the Eye includes one of the first ever anatomical drawings of the human eye and is considered the first systematic textbook of ophthalmology.

Then there was Al Razi, the tenth-century physician and philosopher, author of numerous medical tomes, better known in the West as Rhazes, the greatest physician of the medieval world. His classification of substances into the four groups of animal, vegetable, mineral and derivatives of the three rejected pseudo-philosophical alchemy in favour of laboratory experiment and deduction, preparing the way for the later scientific classification of chemical substances.

His understanding of the nature of time as absolute and infinite, requiring neither motion nor matter to exist, was centuries ahead of its time and has been likened to Newton’s much later theories.

Science was only part of this urban marvel. Baghdad also welcomed polymaths like Al Jahiz, a peerless prose stylist who gravitated from Basra to Baghdad in the early ninth century and over the course of an astonishingly productive career rattled off 231 works, among them the encyclopaedic Book of Animals, which drew heavily on Aristotle and, some would argue, contained the seeds of Darwin’s much later theory of natural selection. The breadth of his interests and output was gloriously, quintessentially Abbasid, ranging from the superiority of black men over whites, pigeon-racing and Islamic theology to miserliness, the Aristotelian view of fish and whether it was permissible for women to groan with pleasure during sex.

Poets were in on the action, too, always eager to dash off a sycophantic verse in the hope of receiving a purse of gold coins from an appreciative caliph. Perhaps the most transgressive of this unruly lot was Abu Nuwas, a wine-quaffing, boy-seducing libertine whose poetry celebrated illicit sex with a fearlessness that would have had him killed in parts of the Arab world today. Abu al Atahiya was another transcendent voice from the eighth century, a penniless pot-seller-turned-poet who somehow managed to keep his head attached to his neck during the reigns of half a dozen caliphs.

But a golden age cannot last forever. That is part of what makes it so special. Baghdad’s time in the sun lasted several world-illuminating hundreds of years but by the thirteenth century the glory days had long gone. The once omnipotent caliphs had retreated behind their palace walls to become indolent, garden-tending puppets controlled by outsiders.

Then, in 1258, the apocalypse came. It arrived in the terrifying form of Hulagu, warlord grandson of the Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan, and his bristling army bent on plunder. The decadent Abbasid regime was no match for his hordes, who wreaked havoc and destruction; after the feeble caliph Mustasim had surrendered, several hundred thousand Baghdadis who had been promised mercy, including scholars and scientists, were hacked down in cold blood.

Then the city was torched. The great Abbasid palaces were consumed by the inferno alongside mosques, law colleges, royal tombs, markets, libraries, and street after street of homes. The Tigris ran red with blood and black with ink from all the books hurled into it. Baghdad, once the most sophisticated civilization on earth, went up in smoke and plunged into the abyss. It never dominated the world stage again.

For all its troubles today, for all the war and sectarian strife brilliantly documented in the BBC series Once upon a Time in Iraq, Baghdad remains a great, resilient city. It may be a shadow of its former, world-beating self, but let us celebrate its continued survival. Happy 1,258th, dear Baghdad. Just don’t mention 1258.

Justin Marozzi is the author of Baghdad: City of Peace, City of Blood and Islamic Empires: Fifties cities that define a Civilization.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe