Will it make any difference? (Getty)

In 1942, an entrepreneurial gourmet named Marjorie Hendricks opened a restaurant in the down-at-heel Washington DC neighbourhood of Foggy Bottom and called it the Water Gate Inn. Two decades later, developers drawing up blueprints for a waterfront complex of six buildings in Foggy Bottom — a “city within a city” — acquired the name from Hendricks and crunched it into a single word.

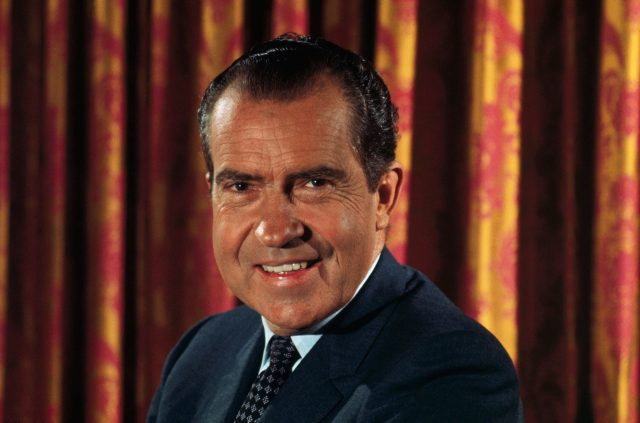

Shortly after midnight on 17 June, 1972, a security guard at the Watergate Complex noticed that someone had taped over several door locks in the main office building and alerted the police, who arrested five men for breaking into the offices of the Democratic National Committee on the sixth floor. On 6 August, after the intruders were tied to President Richard Nixon’s re-election campaign, the Washington Post combined the words “Watergate” and “scandal” for the very first time.

Fifty years on, Watergate remains the political scandal, at least etymologically. Illegal parties at Downing Street? Partygate. A beer in Keir Starmer’s hand at a possibly illegal gathering? Beergate. The people who started a harassment campaign against women in the games industry in 2014 called it Gamergate, and that wasn’t even a real scandal. Even some countries where English is not the first language use the suffix. I suppose the sense of something opening, a threshold being crossed, is somewhat apt, but that’s not the reason why it is used. The man who started slapping -gate onto every potential scandal almost straight away was William Safire, a conservative columnist for the New York Times and former speechwriter for Nixon. Not all of Safire’s coinages stuck, and most are forgotten, but the format endured.

Safire later admitted that he might have been trying to minimise his former boss’s crimes, making Watergate just the first -gate of many. If that was the case, then he didn’t succeed. Watergate is the king of scandals for a couple of reasons. First, it epitomises the power of diligent journalists to bring high-level malfeasance to light. Played by Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman in the 1976 movie, All the President’s Men, the Washington Post’s dynamic duo of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein are still synonymous with dogged, shoe-leather reporting while Deep Throat (“Follow the money”) is the quintessential informant. Woodward and Bernstein were only part of the story but they gave it a halo of heroism. Second, the scandal had a satisfying conclusion: Nixon resigned in disgrace on the brink of impeachment on August 8 1974. Jimmy Breslin called his bestselling book about the scandal How the Good Guys Finally Won.

Watergate inspires nostalgia for a time when political crimes led to punishment. When Boris Johnson can ride out Partygate (for now) and Donald Trump can survive two impeachments thanks to partisan loyalty, Nixon’s downfall seems refreshingly decisive: truth prevailed and justice was served. Like all historical events, it took on an aura of inevitability after the fact. But the chain of cause and effect was not that simple.

The Washington Post’s first mention of the Watergate scandal, in August 1972, came in the context of despair. During Nixon’s re-election campaign, the paper complained: “Such potentially explosive issues as the Watergate scandal go by almost unremarked.” At that point, it had already been reported that the men who had broken into the DNC offices to plant listening bugs had received money from the Committee to Re-elect the President and that Martha Mitchell, wife of the committee’s director John Mitchell, had been held captive in the California hotel to stop her talking to the press. (Her story is the focus of the new Julia Roberts miniseries Gaslit.) A month before the election, Woodward and Bernstein reported that the FBI believed the break-in “stemmed from a massive campaign of political spying and sabotage on behalf of President Nixon’s re-election”. Nonetheless, Nixon went on to defeat Democrat George McGovern in a 49-state landslide with more than 60% of the popular vote, the killer irony being that none of the skulduggery was necessary.

Strange though it seems, at the time, most journalists thought that Watergate was just an amusing caper which cast no shadow on a popular president who was scoring diplomatic coups in Russia and China. Few newspapers bothered to assign full-time reporters to the Watergate beat. On television, only CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite picked up the story. Throughout 1972, Woodward and Bernstein were too far ahead of the media pack, which made Watergate look like the Post’s hobby horse. Nixon’s campaign manager Clark MacGregor accused the paper of using “innuendo, third-person hearsay, unsubstantiated charges, anonymous sources, and huge scare headlines” to cook up a non-existent connection between the White House and Watergate on behalf of the McGovern campaign.

Not until the televised Senate hearings began in May 1973 did Watergate become a national obsession, inspiring comedy albums and novelty gifts such as the “jigsaw puzzle that will bug you”. Around 85% of viewers tuned in at some point. Amazingly, Nixon’s vice president Spiro Agnew was soon under investigation himself on unrelated charges of criminal conspiracy, bribery, extortion, and tax fraud. This shocking scandal, leading to his resignation in October, was a mere sideshow to Watergate.

In a scandal, the best defence is confusion. Nixon and allies such as Ronald Reagan shuffled through the full deck of excuses and decoys. It wasn’t a big deal. It was just a few bad apples. It’s a partisan attack by Democrats in cahoots with the liberal media, a witch hunt, a lynch mob. It’s hurting the country. “For America’s sake, let’s get on with the business of government,” said Reagan. In short, move on.

Having first covered up his complicity in the original crime, Nixon then attempted to cover up the cover-up, and that was the real turning point for public opinion. The administration’s attempt to undermine the Senate investigation let slip the existence of a secret recording system in the Oval Office. Nixon then spent months fighting to block the release of the tapes.

On 20 October 1973, he ordered his attorney general Elliot Richardson to sack the staunchly liberal special prosecutor Archibald Cox, who was demanding that the White House hand over the tapes from the Oval Office’s secret recording system. Richardson refused and resigned. His deputy also refused and resigned. The third in line did sack Cox but this “Saturday Night Massacre” was a colossal miscalculation. Only then did the number of Americans who wanted him to resign finally overtake those who approved of his performance. Even if they didn’t understand exactly what he’d done wrong, they could see that he was acting like he’d done something wrong. Congress took the first step towards impeachment proceedings.

Despite all of that, one in four Americans continued to have Nixon’s back, even after the “smoking gun” tape revealed that the President had been involved in the cover-up since the beginning and triggered his resignation. Nixon and Agnew had energetically stoked white rage and resentment, and that was a faithful constituency. Nixon refused to quit until a posse of Republican greybeards sat him down and told him he was done, 26 months after the break-in.

As Leon Neyfakh’s brilliant 2017 podcast Slow Burn (the source material for Gaslit) argues, it could have turned out very differently. What if Nixon had destroyed the tapes, or there had been no recordings in the first place? What if the Democrats hadn’t held a majority in both houses of Congress? What if partisan polarisation had been as extreme then as it is now? What if influential news outlets had maintained throughout that it was all a smear campaign and reduced the scandal to a political litmus test? Much depended on the integrity of key officials. Elliot Richardson’s loyalty to the administration did not dissuade him from approving the investigations into Nixon and Agnew, even at the cost of his job. John Dean, White House counsel and Watergate conspirator, chose to collaborate with federal prosecutors. The FBI did its job. None of this was guaranteed.

Yet for all the might-have-beens, Nixon did fall in the end. If it took an awful lot to bring down an election-winning heavyweight in 1974, then it’s even harder now, although it’s worth saying that the UK is in a better place than the US. Johnson may still be in office but a majority of voters, and 148 of his own MPs, want him to resign over Partygate. In Washington, meanwhile, only one Republican Senator voted against Trump during his first impeachment and only seven in the second. Even after the storming of the Capitol, his approval rating stood at 34%. Despite the damning findings of the House’s January 6 committee, Trump is still expected to run again in 2024 and may well win. When one Nixon loyalist was asked in August 1974 if new facts such as the smoking gun tape would change his mind, he replied: “Don’t confuse me with the facts.” During the Trump years that would made him a typical Republican.

Perhaps this failure to punish an attempt to overturn an election is a long-term consequence of Watergate. In 1964, 75% of Americans said that they trusted their government to do the right thing most or all of the time; in 1974, after a decade of gradual decline, it plunged to just 36%. It is currently 21% and has only once achieved a majority, immediately after 9/11. By cratering voters’ faith in politicians in general, Watergate bred a pervasive cynicism which took the air out of most subsequent scandals and explains why so many -gates have fizzled out without inspiring high-level resignations or prosecutions. If you think they’re all as bad as each other, then even egregious wrongdoing can seem like filthy business as usual, to the benefit of the worst offenders.

Thus the most paranoid of presidents gave birth to an age of national paranoia. Immediately after Watergate, this suspicion was dramatised by movies such as The Parallax View and Three Days of the Condor in which the truth either doesn’t come out or, worse, doesn’t matter. In All the President’s Men, Robert Redford plays a role in changing history. At the end of Three Days of the Condor, his CIA researcher, Turner, boasts to a senior official, Higgins, that he has told the New York Times all about a rogue operation and the murders the agency committed to cover it up. But as he walks away, Higgins shouts after him: “Hey Turner! How do you know they’ll print it?” Redford’s face says it all.

If the movie were remade now, I think the question would be even more cynical: sure, they’ll print it, but how do you know it will make any difference? How do you know enough people will care?

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe