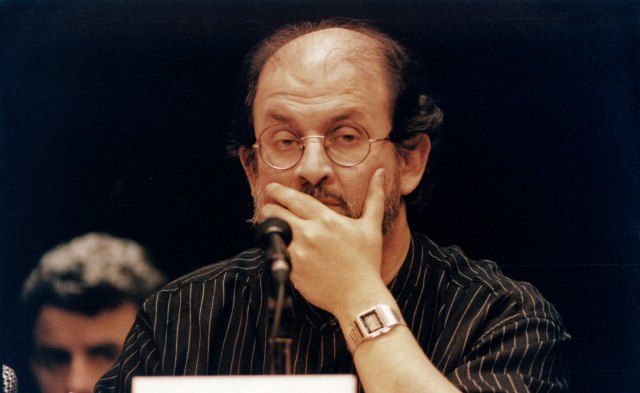

“Free” is a weasel word (Francis DEMANGE/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Sometime in the early Nineties, I found myself standing next to Salman Rushdie at a urinal. The Groucho, it must have been. We looked away from each other with more than the usual degree of concentration. I didn’t like his novels — I found them jocose — and had said so publicly, and he disliked mine to the point of saying nothing about them whatsoever.

But sharing a urinal reminds even warring parties of the humanity they have in common and I suddenly wanted to make a gesture of peace. “Hello, Salman,” I said as we converged on the wash basin. “I have an apology to make.”

I wasn’t going to recant on finding his novels jocose. But I did want to confess to expressing less than unequivocal support for him at the time of the fatwa against The Satanic Verses. Less than unequivocal support didn’t mean thinking he had it coming, as some commentators and even fellow novelists did. I was outraged by the pronouncements against the novel and the threats to Rushdie’s life; but I hadn’t felt I could wholeheartedly endorse the spirit of his apotheosis as champion of free speech.

The argument put forward by John Berger — that Rushdie should have thought harder about the dangers his novel posed to those involved in its translation and dissemination and asked his publishers to “stop producing more or new editions”, if only temporarily — chimed with what I’d been thinking. Berger spoke of a “terrifying righteousness on both sides”, and to me that fairly characterised the Holy War that had broken out between the clerics who wanted the book destroyed and a literary elite for whom its existence had become sacrosanct.

“Elite” is an envious word. You don’t speak about elites if you are in one. And I don’t doubt that a sense of exclusion from a charmed circle of the righteous explains why so many writers who might have been expected to be vocal on Salman Rushdie’s behalf weren’t. The Holy War didn’t only pit the righteous against one another; it pitted people unable to imagine the justice of any position but the one they held. The clerics closed minds, and Rushdie’s coterie of literary admirers closed ranks. Both sides claimed the support of angels.

But the angels arrayed against The Satanic Verses were armed and heaven-bent on destruction, while Rushdie’s angels were only smug, and that should have persuaded me to sing along, if only faintly, with them.

As we washed our hands, I told Salman that. Coming clean, you see. I also told him I admired his courage in trying to live a normal life and speak up against those who wanted him silenced, a courage that wasn’t diminished by his having 24-hour police protection. That, too, must have taken some living with. He patiently allowed me to unburden my conscience and we shook on it.

It’s nice making friends and had I only been able to find a generous thing to say about his next novel we might have remained friends to this day. As it turned out those were the last warm words we exchanged.

I don’t today, in the light of the attempted assassination of Salman Rushdie, feel pulled this way and that. Today there is only horror and sorrow and hope for his recovery. One doesn’t have to be a member of a free-speech elite to know that no books should ever be destroyed and no authors attacked for what they write. From the understandably lavish outpourings of praise for Rushdie’s work over the last week, you could form the impression that the attack on him was particularly heinous because it was an attack on genius. But genius is irrelevant to this. It was an attack upon a living soul. And upon living words. The sacrilege would be as great were the injured writer merely mediocre.

“Free speech”, nevertheless, remains a forever self-contradicting concept. “Free” is a weasel word. Nothing is free of consequences, whether seen or unseen. To uphold this person’s absolute freedom we might make unacceptable inroads into someone else’s. Indeed, it would seem that we are able to revere free speech and abominate it in a single breath.

Witness last week’s extraordinary decision by the Pleasance Theatre — a self-proclaimed champion of free expression and scourge of censorship — to pull the comedian Jerry Sadowitz’s show because it “did not align with the theatre’s values”. The Pleasance’s defence of its actions, that Sadowitz had gone too far, has been rightly ridiculed. Championing free speech until it goes too far is not championing free speech. And the theatre seemed to forget that, as this was a Fringe Festival of Alternative Comedy, the platform it had originally granted Sadowitz was necessarily exempt from the usual civic inhibitions: its decision was an assault on the very principle of sacred space, without which there can be no carnivals, circuses, clowns, comedians or, of course, novelists.

But it’s for requiring a performer’s material to “align with its values” that the Pleasance will long live in infamy. The theatre has not put a bounty on Sadowitz’s head. Cancelling a booking is not the same as a death threat. But demanding alignment with its values puts it in the same camp morally and intellectually as regimes who silence critics of their values. And, at the other extreme, universities and publishing houses who demand conformity with the truisms of the hour.

Until we learn to be more accomplished equestrians, freedom of speech is too hobbled a nag to carry us safely into the uplands of open discourse. We inch along and stumble often. In the meantime, what must be insisted on is that while the offended enjoy the same rights to speak out as the offenders, they do not enjoy more. To be insulted, outraged, hurt, or otherwise assailed by someone else’s words does not confer the privilege of silencing them. Nor is it a university’s job to provide sanctuary from language that does not “align” with its values or those of its students. To the contrary: its most important intellectual function is to teach how to engage with alien ideas and discomfiting emotions. An education that doesn’t prompt radical changes in us is of doubtful value.

It seemed for a number of years that something, somehow, had changed for Salman Rushdie. The fatwa fell silent. Someone had relented or just forgotten. That it had all along been biding its time, awaiting the right moment and the right assassin, is devastatingly depressing. It throws us back into the mouldering inevitabilities of ancient tragedy, where grievances are passed on like the plague and a curse, once made, can never be rescinded. The freedoms we trumpet are an expression of a new hope in a less cruelly fatalistic world. But freedom is a conversation or it’s nothing, and free speech is wasted on us if we won’t take up the challenge to listen freely too.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe