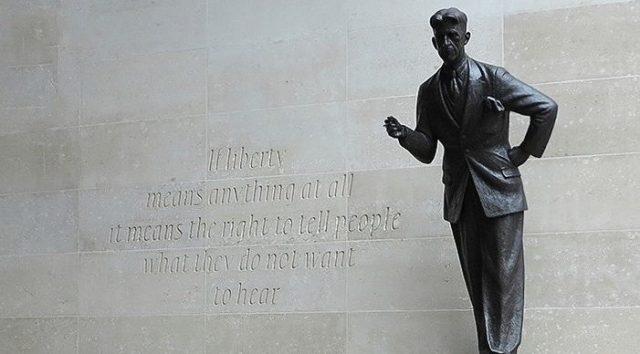

The Orwell statue at the BBC’s entrance. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

It is easy to get infuriated by the BBC’s annual league table of its highest-earning stars. Zoe Ball is an engaging presenter, but should she be paid £1.36m for chatting away on the radio after losing a million listeners? Why do we pay people almost half a million pounds to read an autocue on the evening news? Does Alan Shearer deserve almost £400,000 a year for his dull insights on Match of the Day? What has Ken Bruce done to see his pay package suddenly shoot up by £105,000?

Yet there are far more profound issues facing the BBC than the annual furore over presenter pay. For the institution confronts an existential crisis: it is funded by a tax that defies logic in the modern media world, faces threats from far-richer rivals, and is being assailed from all sides for perceived political bias. It looks like a wounded beast, limping along and licking its wounds while clouds of vultures circle hungrily overhead.

Tim Davie, the new director-general who must grapple with how to protect the state broadcaster in an age of streaming, social media and intensifying culture wars, was greeted in post by a ridiculous row over the singing of Rule, Britannia! at the Proms. This fuss showed the toxicity of so much of the debate surrounding the corporation at this time of unprecedented financial, commercial, political and social challenge. The BBC must deal with hostility from Downing Street in a country that is becoming ever more divided, while trying to find ways to appeal to younger generations that, unlike my own, lack any special affection for Auntie.

It is almost a century since the BBC was founded by Lord Reith with his mission to “inform, educate and entertain”. The birth came in October 1922, exactly one week after the arrival of my own father. Yet my son’s generation sees the £157.50 licence fee as an absurd anachronism when they spend so much time on Amazon, Netflix, Spotify and YouTube — and they scoff at the idea of watching a news broadcast at a fixed evening time amid so many digital offerings. The BBC’s annual report showed people aged 16 to 34 consume only seven and a half hours of its content each week.

The director-general was right to declare “we have no inalienable right to exist”, in his debut speech. Yet for all the BBC’s faults — and there are many — I believe it is a force for good in our nation as we saw at start of the pandemic with its calm, public-spirited response. It is also a crucial part of British soft power and beacon for many people trapped under dictatorship. The licence fee can be seen as cheap when its daily output on radio, television and online costs us one-fifth of the price of a coffee in major cafe chains. But such is the BBC’s unique place in British life that everyone has a view on what it is doing wrong. And mine is simple: it has lost its bottle.

Ever since tangling with the Blair government over Iraq, the BBC has been cursed by tragic lack of confidence as it stumbles from crisis to crisis. Its reaction to each scandal, its response to each savaging, has been to calcify a bit more under tiers of timid managers who are terrified at being perceived as out of touch, condemned by some noisy lobby group or attacked for frittering away resources. The latest annual report reveals the number of these senior managers rose again with an astonishing 106 of them pocketing more in pay than the Prime Minister. Yet the legacy of these swarms of suits is an organisation in funk: stymied by fear, stifled by bureaucracy and suffering clear loss of nerve on news. This makes the corporation harder to defend as it cuts budgets, churns out banal bulletins and screws up digital output.

The BBC employs 6,000 people in news, which includes more than twice the number of journalists as the country’s most successful newspaper group. Yet how often do its main television news shows reveal a domestic story they have not been spoon-fed? Genuine scoops and jaw-dropping stories are far more likely to come from papers, despite their ever-smaller teams and shrinking sales.

Bland evening bulletins on television are fleshed out with analysis of mind-numbing banality designed to avoid causing offence followed by dreary vox pops rigidly controlled to ensure balance. Reporters are sent to stand pointlessly outside empty buildings at night for dramatic effect. Highly-paid editors pontificate but say little of substance. Even the BBC news website that was once strong — if unfairly undermining commercial media — has become a stodgy mess rarely worth the effort of trying to navigate.

There is much talk of diversity as the corporation tries to reflect the country. This is right and proper, both in personnel and issues. Yet attempts to step out of their comfort zone often look patronising. Such is the lack of editorial confidence that when Newsnight tried a segment this week on migration, I was shocked to see it failed to challenge repugnant extremist views — presumably since scared of looking like ‘metropolitan liberals’. At the same time aid is seen as sacrosanct by BBC bosses in bed with Comic Relief and running their own development charity while there is no room for nuance on critical issues such as tackling climate change. “We’ve signed up to the Greta Thunberg agenda,” said one well-known presenter. “I’m not a denier but we’ve lost the ability for any debate around this issue.”

Boredom has become a bigger problem than bias. There are, of course, still fine exceptions to the flow of sludge. The foreign reporting and world service remain strong, their reports and analysis often offering real insight — perhaps since the journalists and editors are freed from fear of upsetting domestic factions. Its recent documentary series on Iraq was stunning, even if downplaying British involvement, while it has delivered big scoops on the atrocities inflicted on Uighurs by Beijing. Yet there is no current Africa or China editor, although one-third of the global population live in these places. “We cover the world through David Miliband,” joked one senior journalist, such is the ubiquity of the charity chief on the BBC — although needless to say, the former foreign secretary is never asked why he pockets almost one million dollars annually in the poverty industry.

I have sympathy for the political team, whose diligent efforts to cover Westminster spark torrents of bile on social media. Panorama has carried out brave and strong investigations, Victoria Derbyshire and reporters such as Jayne McCubbin on BBC Breakfast offer incisive reporting on neglected social issues while the main radio news programmes still cling to Reithian ambitions. But compare the key evening television bulletins, or Newsnight and Channel 4 News — and the BBC too often comes off second best. Meanwhile its flagship Question Time has descended from serious political discussion into a shouting match in search of applause on social media.

Now as new rivals plan partisan news operations and Rupert Murdoch’s Times launches its own radio station, the BBC’s top brass has decided this is just the moment to tarnish some jewels still in its tatty crown. They are axing their remaining national radio reporters, telling them to reapply for a smaller number of jobs as multi-tasking television, radio and digital reporters. This may mark the end not only of the careers of some stalwarts but also the organisation’s era of world-leading specialist radio journalism. Yet there is no attempt to rationalise sprawling news output, although this might deliver bigger savings to invest in better journalism.

I was astonished to learn that Radio Four’s Today programme, the most influential radio news show in the country, no longer has any dedicated reporters. I asked one radio insider what would happen if it wanted to mount a serious investigation into an issue and was told that either this would be carried out by one of the presenters, who may not have a background in hard news let alone sufficient time, or they would have to bid for a reporter from a pool, who would then be expected to offer a variety of reports on the issue for other BBC platforms. Clearly the bean counters and suits care less about news, let alone exposing dodgy behaviour by powerful bodies, than on their misconceived vision of value for money.

Many other issues confront the BBC. Most British citizens turn to the broadcaster for drama, entertainment or comedy rather than its news. The corporation made the mistake of partnering challenger firms such as Amazon and Netflix on programmes, helping to oil their path into the valuable world of British creativity and production. Now these behemoths threaten to devour their host like voracious parasites as they splurge vast budgets on buying up talent.

Maybe the solution is to focus on content rooted in this country rather than outright competition; if something is good enough, it will still sell as proved by The Fall, the crime drama set in Northern Ireland and now a Netflix hit, or Channel 4’s Derry Girls. “If you tell a story well enough you can get a hit because truths and good stories are universal,” said one top UK producer. “But if you try to do everything and reach everywhere you end up nowhere.”

After 30 years in journalism, however, my focus is on news. So here is my advice for Davie: show some confidence, take risks and revive your floundering news operation. Journalism is not about ticking boxes. It should tell stories and cause waves, sometimes even offence, since it is about revealing things powerful people and vested interests seek to hide — and this is why they turn on critics with such force. So sack most of the suits, silence the shallow pontificators and unshackle the editors by giving them more freedom and responsibility. If they deliver dross, miss scoops or fail to connect with their public, find bolder editors and better reporters. Otherwise the BBC news operation will roll downhill as audiences dwindle further.

Every day staff entering Broadcasting House pass a statue of George Orwell. The new director-general needs to remember this great man’s words, that truth is a revolutionary act in an age of deceit, if he wants the BBC to retain support and relevance.

Surely it is better to reassert that noble desire to inform, educate and entertain by sparking debate over enlightening news stories than wave the white flag amid hostility? Otherwise those of us who believe in the BBC are left defending an organisation that is simply indefensible. And those wishing it dead may be among the most distraught when it has gone.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe