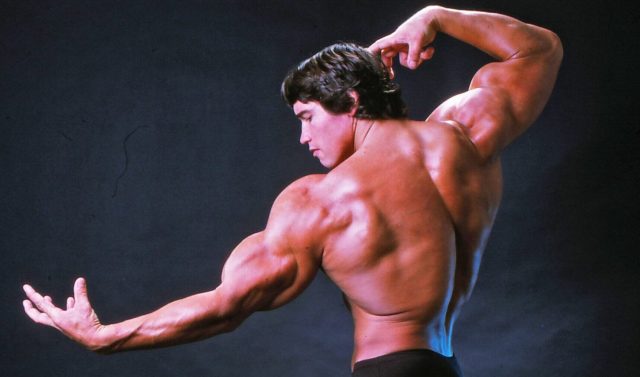

‘What do you do with biceps the size of watermelons?’ Jack Mitchell/Getty Images

I’m not a fan of self-help books. Their prose ranges from dully functional to the equivalent of a hot-breathed salesman prefacing every sentence with your Christian name. Most of these books are based on the experience and expertise of their authors, and on investigation much of the experience and expertise turns out to be false. Still, if any public personality has a claim to write a self-help book, it’s Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Schwarzenegger can legitimately call himself a self-made man. He came to the US with no money and an unpronounceable name and a skill that was barely viewed as a skill and had no obvious practical application: what are you supposed to do with biceps the size of watermelons? With fanatical discipline and a lot of personal charm — along with the benign bullshitting the Austrians call schmäh — he parlayed his skill into movie stardom and eight years as the Governor of California; he wasn’t that bad a governor, either. If the US had a different Constitution, he might have become President.

If you watch the 1977 documentary Pumping Iron, the movie that first introduced Arnold to a mainstream audience, it’s clear that even as a neophyte he viewed what he did as self-construction. He compares himself to a sculptor. “You look in the mirror, and you say, ‘Okay, I need a little bit more deltoids, a little bit more shoulders,’ so you get the proportions right. So what you do is you exercise and put those deltoids on, whereas an artist would just slap on some clay on each side. And, you know, maybe he does it an easier way. We go through a harder way.”

Schwarzenegger’s gift for canny, accessible analysis is no doubt present in his new self-help book Be Useful: Seven Tools for Life. Judging by the book promo, the tools are rooted in common sense. Have a vision of what you want to achieve, work hard to achieve it, promote yourself whenever you can, reinvent yourself. I wouldn’t argue with any of this (well, maybe the self-promotion), and especially not the last. If Arnold is anything, he’s a dedicated reinventor. Consider the penitential regimen of exercise and nutrition needed to transform a more or less ordinary looking adolescent (he began body-building at 15) into a hybrid of animated athletic trophy and anatomical illustration. Then consider what it took to transform such a person into a movie star.

In this regard, much of his success came from his embodiment of masculinity, or a particular kind of it. Given Schwarzenegger’s staggering proportions, the great knotted wedge of his torso, the arms like thighs and the thighs like trunks, the jaw that might have been designed to crush bones, we should speak of hypermasculinity. The actors who embodied manhood from the Forties through to the Seventies were physically ordinary or extraordinary only in their beauty, such as Paul Newman or the young Brando. John Wayne and Jack Nicholson were actually kind of dumpy. Jimmy Stewart was a weed. It’s true that bodybuilders before Arnold became action heroes — notably Steve Reeves, who played Hercules in low-budget spear-and-sandal pictures — but they weren’t stars. They were barely actors.

If Schwarzenegger began his career as a growling, jut-browed human tank processing over the rubble of his adversaries, he learned to work his size and menace more agilely. Then he learned to work against them. His best acting is in comedies such as Kindergarten Cop, Twins and Junior, in which his character becomes pregnant via an experimental drug. His comedy is the comedy of masculinity placed in milieus where masculinity has little use, and is even a disadvantage. How is a little kid likely to react when a man Schwarzenegger’s size and with Schwarzenegger’s accent asks him “Who’s your daddy?” It’s the comedy of a giant trying to repair eyeglasses with the tiny screwdriver and even tinier screws that are sold as eyeglass-repair kits.

This gameness and deftness with which Arnold parodies his masculinity — maybe all masculinity — actually makes him more masculine. In a post-Freudian, post-feminist age, we’ve learned to be suspicious of men who make too big a deal of their manliness: they’re either closet-cases or sociopaths. Maybe what I mean is that we’ve learned to be suspicious of men who are humourless about it. And, as my wife pointed out, humour is one of the ways men have always made themselves attractive to women (and perhaps to other men). If a couple of guys are chatting up women at a bar, you can tell which one is dominant because he’ll be the one to crack a joke.

It turns out that Schwarzenegger also trained to make a butt of himself. In a recent interview, he reveals that his tutor was the veteran comic Milton (“Mr. Television”) Berle, who bullied him through take after take of a single joke and called him “Nazi”. It is indicative of the humour that offsets Schwarzenegger’s tendency towards self-promotion. (From the same interview: “There’s a schmäh with everything. Sometimes people take schmäh meaning you’re lying, which is not what it is. It’s kind of like, you wrap it up in a more attractive package. In order to sell something you have to have the schmäh”.) But then self-promotion is inherent in the self-help genre. Why would you take advice from someone who isn’t great at what he does — great at life — and how do you know he’s great unless he tells you, over and over and over?

Schwarzenegger’s self-promotion has always seemed heaviest when he is talking about his political career — though, unlike other political self-promoters, he actually matches his claims with political action: see his fleet-footed response to the 2007 wildfires that swept Southern California. Other times, it’s not clear what the didactic purpose of his political career is. Consider his decision, against medical advice, to be sworn in for his second term as Governator with a broken femur. I wouldn’t listen to anybody who told me I should attend a long public ceremony while standing on a recently broken femur, even one that had been bolted back together. To his credit, I don’t think Schwarzenegger has ever said that. But I also don’t think Tony Robbins actually said that his fans should walk on fire, yet it was something he did at his “seminars”, and a number of attendees tried it. (They sued him after they were badly burned.)

But who hasn’t made a few mistakes? If you want a self-help book written by someone who hasn’t made any, that leaves you with the Bible, the Qu’ran, the Vedas, and the Buddhist sutras. And look how well people follow their advice.

Judging by the material already published, I suspect the contents of Be Useful will be unexceptionable, and probably as good as any advice can be that isn’t given in person, by somebody you know who isn’t a god or a saint (or maybe a chatbot). Yes, we’re talking about an actor who became famous for wise-cracking as he pounded someone’s face to jelly and, before that, for declaring (in Conan the Barbarian) that the best thing in life is “to crush your enemies, see them driven before you, and to hear the lamentations of their women”. But we’re also talking about a tough but warm-hearted gym trainer who reads Nietzsche and the Stoics. He’s demanding. If your reps are half-assed, he’ll make you redo them. But he understands failure; he probably even sees the value of it. “Good job, dude,” he’ll tell you. And you’ll be grateful.

Sometimes his leniency is frustrating. I’m thinking of the speech he gave to the American public after January 6. It was an affirmation of American values and a warning against fascism, delivered by someone whose own father had fought for the Third Reich. That’s what makes it so moving. The speech, however, was notable for its refusal to denounce individuals apart from the coup-leader-in-chief. To me, that’s its one failure. The violence the former president inflicted on our nation was abetted by thousands of allies and followers. They should have been called out. But I’m writing as someone whose father was driven out of Austria following that country’s annexation into Greater Germany. Schwarzenegger’s father may have been in the crowds that cheered Hitler as he entered Vienna; he would have been wearing a swastika armband, since he belonged to the SA.

But Schwarzenegger’s forbearance may speak to an essential sweetness of character. A man can have such a character even if he makes a fortune playing a killing machine or sexually exploits women. Maybe what I mean is really childlikeness. The Governator (one can’t really speak of him as the former Governator, can one? It’s unlikely there’ll be others) gave his January 6 speech using a prop that he invoked as a metaphor for democracy. It was the sword from Conan. In a recent promotional video, he uses the same sword to slice open a carton of the new books. Even grown men love their toys. And as schmäh, it’s priceless.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe