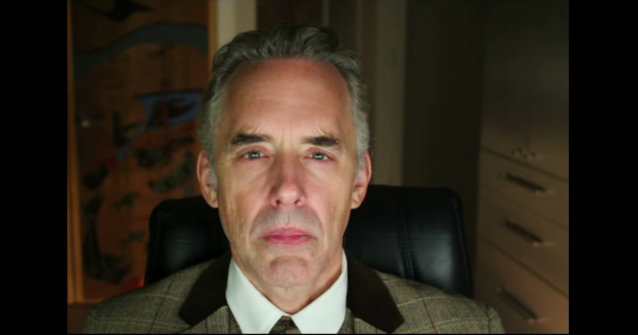

He’s back: Jordan Peterson

The world needs Jordan Peterson. That may sound like the statement of a fan or a friend — and I am both — but it is also a fact illustrated by the sheer numbers who come to him seeking guidance and help. There has been no other public intellectual in recent years who has attracted the kind of following Peterson has. His book, 12 Rules for Life, sold by the millions; his speaking events drew thousands of attendees, night after night, in cities across the world, in what became a gruelling schedule for Peterson. And this was not some top-down publicity-led phenomenon: it was a grass-roots movement in which readers and viewers gravitated towards the Canadian academic.

But then, a year ago, the world lost Peterson. He disappeared from view and it was eventually announced that the professor had been checked into a rehabilitation facility after developing an addiction to benzodiazepines, an anti-anxiety drug which is widely available in the US and other countries. Speculation has been rife ever since about whether he would ever be back and exactly what happened to him during this dark and painful period.

This week we got some answers, with a video in which, speaking directly to camera for the first time in a year, the professor gave some details of what had happened since his last public appearance. As Peterson related, he became hooked on the medication after upping his dosage, apparently in the wake of his wife’s diagnosis and treatment for cancer last year.

He attempted to get off the medication himself, but found that no American facility would allow him to go full cold turkey on the drug, and so he ended up in a facility in Russia where he successfully freed himself from the drug but almost died in the process. Since then he has been in rehabilitation facilities in a number of other countries but — as he announced in his video — he is now finally back home in Toronto.

This and much more will doubtless be pored over by the professor’s friends and fans, and Peterson’s readers and audience members were more than that. They were people who gravitated towards him because they believed — knew — that here was a man who could help them make sense of some of the chaos in their own lives and in the world around them. Many authors have signing-queues in which readers tell them how much their books have meant to them; Peterson’s readers told them how he had changed their lives. I saw this first-hand, with people explaining how, since becoming acquainted with Peterson’s work, their lives had transformed. It would be easy to scoff at this — but it would also be wrong.

One of the strangest and most baffling aspects of the Peterson phenomenon has been the way in which his critics failed to contend with his points and arguments. And not just the specifics, but the fact that anybody with such a following must be onto something. Of course critics primarily on the ideological Left claimed that Peterson was some kind of fringe “alt-right” figure, against the evidence of any and all of his words. It was telling that they remained so incurious about the popularity of his work.

You would have thought that if any Canadian professor who had previously been obscure rose to prominence across the world, with audiences of thousands rising to their feet to welcome him every night, then whatever their ideological stance people — including critics — would try to work out what it was that he was onto. Yet Peterson’s critics, from Cathy Newman to the New York Times and the BBC, consistently failed to see any interest in the bigger story. They tried to bring him down, of course. They tried to portray him as some kind of monster, trip him up, laugh at him or otherwise reveal some underlying horror.

But they never even bothered to contend with the question of what it is that such a person might have been onto. What was the cause of his rise? Why were so many people attracted to his message? When they pretended to answer this question, it was that Peterson was speaking to embittered incels, or some other fringe, unsympathetic group. It is to their long-term detriment that they failed to consider this deeper question: that Peterson spoke to such a wide array of listeners because he was hovering right over the questions of meaning and purpose, which almost everyone else in our society had decided to abandon. Including, but by no means limited to, the Church.

The video that Peterson recorded this week has a number of things which will especially interest fans. The first is that he has been writing, a fact that will give his legions of fans and admirers the opportunity to hope that there will be a follow-up to 12 Rules for Life. That alone is a cause for some optimism, because it holds out the possibility that Peterson has been able to order his thoughts and perhaps continue to think through the challenges which afflict everybody in modern society.

At a time when we have all the confusions of post-modernism raging around us, and now with the overlay of a global pandemic to make some of that movement’s assertions even more unhelpful than they already were, an intervention from Peterson will provide hope to a considerable number of people.

Peterson watchers will also notice that he signed off by saying that “With God’s grace and mercy” he hoped to complete some of the tasks which he lays out in it. In 2017, Peterson released a set of online videos about the first book in the Bible — Genesis — and it had long been his hope that he would be able to find the time to study and prepare for a similar set of lectures on the next book, Exodus.

Indeed this was the primary purpose of the visiting professorship that Peterson had been awarded at the Divinity faculty at Cambridge University — an unpaid position that Peterson was looking forward to taking up until the university authorities discovered that he had once been photographed beside somebody wearing a T-shirt that said “I’m a proud Islamophobe”. I say that this was the ostensible reason, only because it was. As I wrote here at the time, it was clear that Cambridge was simply giving in to a small online mob that remained dedicated to attacking and humiliating Peterson at every turn.

But although the breathing-space that position might have afforded him was taken away, Peterson clearly still intends to go ahead with his chosen task. And it looks like this and other books in the Bible are going to be his main source of study and thought in the period to come.

Fans and readers of Peterson will welcome in any and all of this. His detractors will naturally continue to find reasons to lambast and deride him — but they miss a lot of opportunities in doing so. The world is in an exceptionally confused and bewildering state at the moment; there has rarely been a time when society has had so few thoughtful public figures and so few respected public institutions.

The past as well as the future is being ripped up and ripped apart on a daily basis. If, in the midst of that melee, Peterson finds that purpose and meaning can be found in returning to the books that form the foundation stones of the Western tradition, then that is something that should be cause for reflection. Peterson looks and sounds like he has been though a lot, but perhaps the world that we are entering will need such a guide.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe