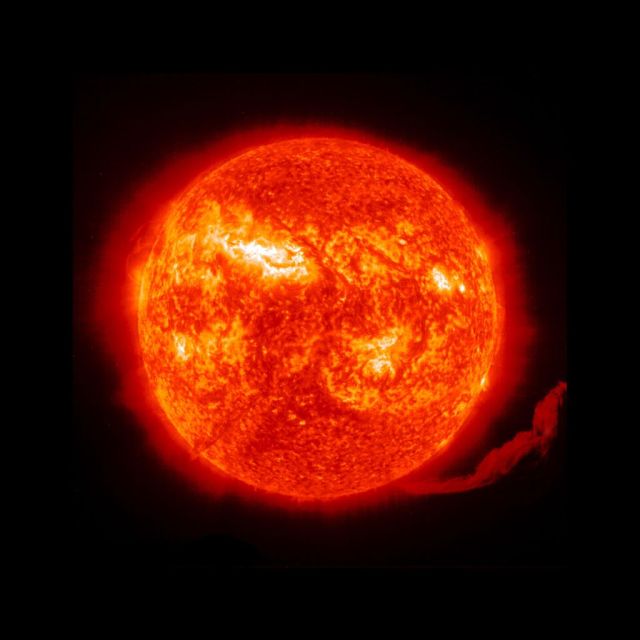

Can we dim the sun? (Photo 12/Universal Images Group via Getty)

We live in an age of climate doomerism, and culture has responded in kind. One of its best avatars is Bong Joon-ho’s 2013 film Snowpiercer, set on a Snowball Earth created when scientists released aerosols into the sky in a last-ditch attempt to stop global warming. The plan catastrophically backfires, wiping out most life on the planet, and leaving Chris Evans and Ed Harris in 2031, trapped on board a train bearing the last remnants of human life and ceaselessly circumnavigating the Earth. When I first saw the film, I remember thinking: “Thank God no one would be crazy enough to try something like that in real life.”

I was wrong. Over the past six months, several governments and international organisations — including the White House, the EU, the British research agency ARIA, the Climate Overshoot Commission, and various UN bodies — have produced reports that cautiously advocate the very same idea: releasing aerosols into the atmosphere in order to block sunlight from hitting Earth’s surface. The concept is known as solar engineering, or solar radiation modification (SRM), and it’s a specific type of geoengineering aimed at offsetting climate change by reflecting sunlight (“solar radiation”) back into space.

The idea of solar engineering is not new, but for a long time it was relegated to the fringes of the scientific community — and the realms of science fiction. However, as the very existence of these reports makes clear, the concept has been attracting more and more attention in recent years, largely thanks to the growing panic over climate change. And much of the interest in solar engineering stems from the fact that, unlike other climate mitigation policies, which require decades to yield any significant results, “SRM offers the possibility of cooling the planet significantly on a timescale of a few years”, as the White House report claims, even to “the preindustrial level” according to “highly idealised modeling studies”.

That report followed on from a 2021 study by the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), “Reflecting Sunlight”, which suggested that “the US should cautiously pursue solar geoengineering research to better understand options for responding to climate change risks”. Mark Symes, director of the UK’s research agency ARIA, agrees: “Through carefully-considered engineering solutions it may eventually be possible to actively and responsibly control the climate and weather at regional and global scale.” Earlier this year, more than 100 scientists signed an open letter calling on governments to increase research into solar geoengineering.

Scientists point to large historical volcanic eruptions — which result in massive quantities of sulfur dioxide and dust particles being spewed into the atmosphere — as examples of the effectiveness of “stratospheric aerosol injection”. They’re not wrong: the 1815 Tambora eruption cooled the Earth by 0.7°C and led to a “year without summer”; more recently, the eruption of Mount Pinatubo, in 1991, cooled the planet by about half a degree Celsius on average for many months. So, the idea goes, by spraying a certain amount of sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere, we could replicate the effects of a major eruption and cool the Earth. Problem solved?

Not quite. All the reports acknowledge that there are serious risks associated with solar radiation modification, which could affect human health, biodiversity and geopolitics. That’s because modifying sunlight could alter global weather patterns, disrupt food supplies and in fact lead to abrupt warming if the practice was widely deployed and then halted. But despite such caveats, the very existence of these reports represents a huge opening of the Overton window when it comes to the issue of geoengineering. Indeed: “The fact that this report even exists is probably the most consequential component”, Shuchi Talati of the Alliance for Just Deliberation on Solar Geoengineering crowed after the White House’s report.

In other words, what matters here isn’t so much the content of these reports — which rightly highlight the risks of such interventions, and the need to proceed with caution — but the mere fact that the issue is treated as a topic of legitimate debate, thus slowly getting the public accustomed to the concept. But even more worryingly, perhaps, now that the geoengineering genie is out of the bottle, can we really expect governments and institutions to keep it under control?

After all, we live in an era in which private and corporate power has largely unshackled itself from any forms of meaningful public control, when it hasn’t outright merged with the institutions of the state, subordinating the latter to its own logic. As a result, billionaires, philanthrocapitalists and investment funds arguably exercise a greater influence over society than most governments. And, of course, they love playing God — especially when it offers massive opportunities for profit. So perhaps it is no surprise that much of the pressure for solar engineering also comes from this rarefied community.

In a speech to the Munich Security Conference last year, George Soros endorsed using solar geoengineering to combat climate change. Jeff Bezos has partnered with the National Center for Atmospheric Research and the geoengineering non-profit SilverLining, closely tied to Silicon Valley venture capital, to help create models that show what would happen if we blocked out some of the sun’s rays. Facebook billionaire Dustin Moskovitz, co-founder of Open Philanthropy, is another major funder of SRM projects. And then there is, of course, the ever-lurking Bill Gates: in 2021, he backed a sun-dimming project by the Harvard Solar Geoengineering Research Program called the Stratospheric Controlled Perturbation Experiment (SCoPEx), which aimed to spray calcium carbonate into the atmosphere in the skies over Sweden to test its effects on sunlight scattering.

The project, however, was strongly criticised by environmentalists and indigenous groups, with 30 groups of indigenous peoples from around the world calling upon Harvard University to abandon the Gates-backed plans to test its solar geoengineering tech. “We do not approve legitimising development towards solar geoengineering technology, nor for it to be conducted in or above our lands, territories and skies, nor in any ecosystems anywhere,” stated a letter from the Saami Council, which represents Saami people across Scandinavia and in Russia. In the end, the test was called off. But this didn’t stop the ominously named American start-up Make Sunsets, which focuses on stratospheric aerosol injection — “Cooling the planet one reflective cloud at the time” — from carrying out several tests in the United States.

This means that sun-dimming experiments are already being conducted by private companies, with little or no oversight or regulation. And the edging of this technology into reality is part of a more general phenomenon in climate action: the emergence of a “climate power bloc” encompassing liberal-technocratic politicians, certain climate scientists, environmental NGOs, “green” philanthropists, and Silicon Valley “climate capitalists”. At this intersection of ideology, class and economic interests, extreme and ambitious ideas such as solar engineering find fertile ground. And they are primed to grow further into the popular consciousness — which has already been conditioned to think of climate change as an apocalyptic threat, and to therefore accept “do or die” solutions.

Activists and scientists have started to push back. We’ve already seen the successful prevention of the SCoPEx test. Then, last year, more than 60 senior climate scientists and governance scholars from around the world published an open letter, since supported by more than 450 academics, calling for an “International Non-Use Agreement on Solar Geoengineering”. They emphasise the very serious risks: to human health, but also to the ecosystem itself, with precipitation patterns, vegetation and crop production all disrupted.

The problem, as is often the case, is mission creep — the gradual broadening of the original objectives of a certain programme, often under the influence of technological path dependency. Once a technology comes into existence it tends to be used for the simple fact that it exists, especially if it has been normalised for the public. Hence the call for “research into solar engineering” is, wittingly or not, paving the ground for its future adoption. And its advocates have an existential climate discourse on their side. SRM lobbyists can always claim that the alternative is worse — if that alternative is planetary extinction. As Anote Tong, a former president of Kiribati, a low-lying Pacific island state menaced by rising sea levels, told the New Yorker last year: “It has to be either geoengineering or total destruction”.

In this sense, the debate over solar engineering is symptomatic of how we are interpreting climate change: as a utopian speculation created in response to the dystopia we increasingly see as our future. This logic is designed to spur humanity into action, to find answers to the climate crisis that avoid vicious socioeconomic costs — which is why some sceptics of radical decarbonisation are sympathetic to solar geoengineering. It’s also why climate change activists such as Greta Thunberg oppose it — because it would threaten commitments to decarbonisation. We should oppose this binary logic. We shouldn’t have to choose between radical decarbonisation and geoengineering: fuelled by an impetus towards climate doomerism, they are both dangerous in their own way.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe