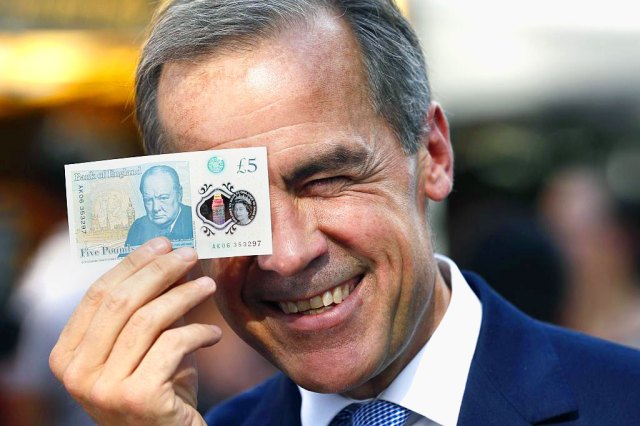

Will normal people understand him? (Photo by Stefan Wermuth – WPA Pool/Getty Images)

In these isles Mark Carney is mainly known as the smoothly suave former Governor of the Bank of England, imported from Canada by George Osborne in 2013 at no small cost to the taxpayer. The tagline “reassuringly expensive” could have written for him. After his term at the Bank ended last year, Carney headed back in Canada (“bloody Ottawa”, he said in one recent interview), where he’s making yet another mountain of money and is clearly a bit bored. So he’s written a book setting out his ideas about fixing economics and politics and generally saving the world.

Carney, of course, is a near-perfect specimen of homo financicus, a recent offshoot of common humanity that seems to sleep less, read more, earn more, do more than the rest of us. Among other things, Value(s) could be a field-guide to the subspecies: its PhD-holding author runs marathons, gets up before dawn to meditate and read the Classics. He analyses international finance with penetrative intensity. A father of four, he’s 56 years old but doesn’t even have the grace to look it. Some people think he looks like George Clooney. If he sometimes sounds a bit pleased with himself, we should remember that he has quite a lot to be pleased about.

But if Carney himself is relatively easy to describe, his book is much less so. Several famous names have had a go. Subtitled Building a Better World for All, it comes larded with glowing quotes from the likes of Bono (“a radical book that speaks out accessibly”) and Christine Lagarde (“Indispensable”). These endorsements are a pointer to the worst thing about the book: Carney’s namedropping. He frames the entire narrative as the result of a slightly over-written lunch with the Pope, and his cast of characters comes from the upper slopes of Davos. Not that Carney is wowed. Most super-famous people are disappointingly normal, he declares, though he admits to being impressed by Emmanuel Macron, the Grand Shiekh of the Al Azhar Mosque, Bono himself, and Greta Thunberg.

Unlike some of the names thus dropped, Thunberg’s walk-on part in this book makes sense. The author meditates long and hard on the greatest problem facing twenty-first century politics: climate change. He’s impressive on the technical and intellectual challenges involved in making huge changes now to avert a disaster that could still be several decades and many electoral cycles away. But can a matinee idol technocrat with a big brain and sharp suit take the people with him? Is Value(s) Carney’s first step into real politics?

He certainly likes to talk about “leadership”, dedicating page after page to the topic. But sadly, it turns that out what he means, most of the time, is “management”. Cue endless lists of the sort of bland wisdom familiar to anyone who’s ever set foot in a business school:

“Leaders are different in that they have to decide. In the end, to lead is to choose… When you take decisions as leader, it will obviously help greatly if they are the right ones… People will respect a leader who has integrity and who is benevolent, but they won’t always follow them if they are not deemed to be competent.”

Sometimes this stuff is sprinkled with some erudition and cod humility: “When I worked at the Bank of England, I would remind myself each morning of Marcus Aurelius’ phrase ‘arise to do the work of humankind’.”

Frankly, the classical references are easier to swallow than some of the jargon. Carney’s thoughts on the nature of the company, corporate purpose and how to encourage businesses to behave better — and make a profit by doing so — are genuinely impressive. If politicians engage with them, we may end up with a better, fairer and more sustainable capitalism. But Carney’s editors haven’t helped him welcome new readers to the subject. See, for instance: “IIRC is working with IASB, GRI and SASB to create a cohesive interconnected reporting system (though the IMP work).” To which even readers who like to think they’re au fait with corporate governance reform might say: WTF?

Carney’s lapses into impenetrable jargon are understandable; he’s never really had to communicate clearly to the masses. Yes, central bankers talk in public, but generally as opaquely as possible. Among his global colleagues, Carney was a chatty charmer, but the bar was low. He talks a good game about always remembering the need to win and maintain public confidence — and even makes a stab at claiming deep legitimacy for independent central banks by invoking Magna Carta. But the truth is that, while those banks are given considerable autonomy by politicians to take decisions that have profound effects on the lives of voters, they are not directly accountable to those voters.

Carney is no rabble-rouser. His idea of the BoE getting down with the people is updating the portraits on bank notes. More telling is what he doesn’t mention. Nowhere, in almost 600 pages, does he find space to discuss quantitative easing — the “extraordinary” monetary policy that continued on his watch. Creating new money to buy bonds, and lower interest rates, had a profound social and political impact. It saved businesses and saved jobs; without it many people, especially younger and poorer ones, would have suffered significant hardship. But the side-effect was pumped-up asset prices. Effectively, central banks made people who own property much richer, and made it much harder for people who don’t own property to buy it. Voters are owed more of an explanation for this than Carney offers.

But when you have a hammer, problems look like nails. If you’ve worked as a carpenter, you tend to want to make things out of wood. And so Carney is keen to take the model of independent central banking into climate change policy, proposing “independent Carbon Councils” that would make quite profound decisions about the price of carbon emissions. He’s careful to maintain that, in the end, elected leaders must sign off big distributional decisions, but makes no bones about trying to find ways to keep those decisions away from voters: “Delegating responsibilities helps insulate decisions with significant long-term implications from short-term political pressures.” Never mind addressing such pressures, let’s just duck them — a novel approach to “leadership”.

For all that, Carney’s book is still good — and the best bits are very good indeed. Unlike some global-minded liberal types, he recognises that the nation still matters. He sees patriotism as not just legitimate, but a way of actually helping countries work together on big problems. He understands that markets haven’t worked for everyone and won’t without sensible state action. He offers a lot of ideas about things like skills, education and employment that would make economies more productive and societies fairer. And his critique of “market societies” in which common values have been eroded, and individualism trumps social obligation, should be read and absorbed by every technocratic centrist wondering why those terrible populists do so well despite their terrible policies. “Building social capital requires a sense of purpose and common values among individuals, companies and countries,” Carney says.

That might sound like an uncontroversial statement of post-liberal orthodoxy — but remember that Carney himself is no post-liberal. He’s not just a Goldman Sachs-educated archduke of Davos: he’s a potential Liberal Party prime minister of Canada. And whereas the current holder of that title, Justin Trudeau, has largely embraced the identity politics that is rendering liberalism illiberal and unattractive, Carney’s book has no time for any of that — or for Trudeau himself. Other technocratic leaders get approving namechecks, but there’s not a single word about Canada’s current PM. Subtle, eh?

Value(s) has enough ideas to fill a manifesto, but gives no overt sign that Carney is plotting a political career — an omission that suggests he wants to keep his options open. Could homo financicus make a sudden evolutionary jump to become a full-blooded politico? Less accomplished men have done so before him: Macron is an ex-banker who had a fraction of Carney’s experience when he took the Elysée; Trudeau, on the other hand, was a supply teacher. Barack Obama a law lecturer.

But those leaders are not the real comparators here, not least since they have all, in different ways, failed to live up to expectations. The liberal centre, the tribe of just-do-what-works technocrats, has lacked truly successful leaders since Bill and Tony were taken from us. Clinton and Blair were policy wonks and globalists who could still instinctively feel the mood and priorities of people who loved their communities and their countries. They have had no true heirs. Obama talked the talk, but in the end couldn’t hide his scorn for “bitter” people who “cling to guns or religion”. David Cameron put on a decent act but lacked conviction or spine. Even his greatest fans wouldn’t claim Joe Biden will define an era in the way Clinton and Blair did.

Could Mark Carney take the good ideas from his impressive book and try to make them work in the messy world of politics? If he did and it worked, he’d be the closest thing the real world has seen to the West Wing’s Jed Bartlet: a liberal intellectual technocrat with a devout Catholic’s social conscience — every sensible centrist’s political fantasy. But then, fantasies are fictional for a reason.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe