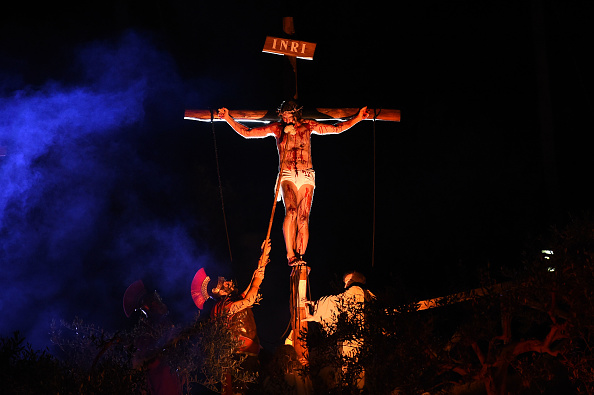

“I saw my first crucifixion at boarding school”. NurPhoto / Getty Images

I was little more than a child when I witnessed my first act of crucifixion. A young boy was hoisted up on a dark wooden bar in the dormitory, arms tied down with dressing gown cords. He was terrified, his body restrained with strips of knotted fabric, legs dangling in space, mouth stuffed with socks so that he would not attract the attention of teachers who were downstairs having a drink.

Some thought it was a bit of a laugh, that all-purpose justification for brutality the world over. And with just enough boys involved to make it a collective effort, individual responsibility was dissolved away in the frenzy of a Dionysian joint enterprise.

Others didn’t know what to do. They watched or slunk away, not wanting to be next. But there would be no escape. Bullying was cyclical. One day you were the bully, the next, you were the bullied. The roles were very swiftly transferable: victim one day, victimiser the next. Pretty much everyone was involved. A kind of omertà pertained, generated by a mixture of fear and shame. The Lord of the Flies wasn’t fiction at my school.

Few people who were at boarding school back in the Seventies can have escaped the effects of this brutal and brutalising culture. Free a group of young boys from parental control and leave them largely unsupervised for hours on end… Only those with the most blindly naïve view of human nature could be surprised at what happens next. And when the school is itself run on the basis of gratuitous violence — beatings being the only language of moral instruction I can recall — one has all the elements of a little lesson in the social dynamics of the crucifixion.

Perhaps the most challenging thing for a congregation to accept during Holy Week is that the people who welcome Jesus into Jerusalem at the beginning of the week are those same people who jeer for him to be crucified a few days later. All the signs were that this man was the Messiah — half religious leader, half king — who would return the Jewish people to the glory days of Kings David and Solomon. The Messiah was the charismatic frontman for the Make Israel Great Again movement. The sort of person who could draw a crowd, get them all excited, hold them in his hand.

Palm Sunday has all the energy of a Trump rally in a football stadium, with crowds pouring down the Mount of Olives to hail their hero’s triumphant entry into the city. I have joined those crowds myself on Palm Sunday and, even though we know what follows, it still feels like religious enthusiasm at its least self-critical. Punch the air. We are on the winning side.

But when squeezed inside the political cauldron of Jerusalem, something changes. Within days, maybe even within hours, the perspective flips. The all-conquering hero suddenly looks like a funny little man from provincial Galilee, someone who won’t stand up for himself, someone who allows himself to be bossed about by the authorities. And all that nonsense about turning the other cheek. What a loser. And messiahs can’t be losers. The cries of “Hosanna!” fade away to be swiftly replaced by “Crucify!”.

The crowd is the great villain of Holy Week. More so than Judas, the betrayer. More so than Pilate, the pragmatic amoral politician, straight out of central casting. More so than Peter, the denier. The crowd has a kind of demonic corporate personality: fickle, gratuitous, devoid of conscience, at turns both sentimental and brutal. In the crowd, you can no more be blamed for your actions than a starling can be held responsible for the direction of a murmuration. Everyone has deniability, no one has blood on their hands because everyone has blood on their hands.

In the Gospels, the crowd functions much like the Ring of Gyges, a mythical band that grants invisibility to those who wear it. Plato talks about it in Book 2 of The Republic, where he asks if any of us, when freed from the possibility of detection, would be so virtuous as to resist the temptation to do whatever our passions might compel. The Gospels suggest not.

The liturgy of Holy Week is designed to call us out, to expose the way we flit from friend to betrayer the moment our own security is threatened. If the liturgy is doing its job properly, Christians should recognise themselves as the very people who are screaming to string him up. And piety does not save us from being among their number. There is something more than a little ironic about that. Holy Week is packed full of religious services. Yet Holy Week is also a thoroughgoing attack on religious piety, whereby the more religious you are, the greater your failure.

So, for example, Peter’s denial of Christ — “Nope, I don’t know him” — wasn’t just a one-off. Three times he pretended he wasn’t one of them. And yet, it is from this unpromising material that the church itself is created. Peter was the first Pope.

This Christian attitude is the absolute polar opposite of that debased and moralistic approach to human values that is known as cancel culture. In cancel culture there is no way of coming back from the taint of guilt. In cancel culture everyone is encouraged to see themselves as a victim but no one has the courage to admit they have been the victimiser — except, of course, in the most general of terms. And the two are connected. Cancel culture offers no redemption, so encourages only the denial of one’s complicity. By contrast, Holy Week offers nowhere to hide from our own cowardice and failure. In this story, we are the betrayers. And yet this is also the one where we emerge transformed.

And that, in the end is the weakness of cancel culture moralism: it leaves everything where it is. People are not changed. In the quiet of Holy Week, I can admit the painful truth that I was a bully too. Both a victim and a victimiser. I looked away when I should have stepped in. I too pretended it wasn’t going on. Because if you can’t admit it, you can’t heal it.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe